California puts redistricting on the ballot in response to Texas

As partisan redistricting efforts escalate in states across America, the nation’s most populous state is getting ready to make its move. Next week, voters in California will decide whether to approve a new congressional map that could result in five more Democratic seats in the U.S. House. Polling indicates that the measure, known as Prop. 50, is likely to pass handily.

The new map will temporarily replace a nonpartisan one that had been drawn by an independent commission, which Californians had previously voted to support. But in response to aggressive Republican redistricting efforts in Texas and other states, many Democrats here, including some commission members, now say the state needs to fight fire with fire.

It’s a turn of events that brings Sara Sadhwani “no joy.” But the Democratic member of California’s independent redistricting commission says she believes her state must act to mitigate a GOP power grab elsewhere. Democrats need to win control of the House, she says, to put a stop to President Donald Trump’s “violations of the U.S. Constitution.”

Why We Wrote This

A dozen states are drawing new congressional district maps, or thinking about it, as Republicans and Democrats maneuver for control of the U.S. House after the 2026 midterm elections. The efforts could diminish the importance of individual voters.

Normally, congressional maps are redrawn every 10 years, based on new census data. But now, at least 12 states are either drawing new maps or considering it. The movement started in August, when President Trump urged Texas Republicans to create a new map to try to get his party five more seats in the U.S. House – an attempt to blunt potential Democratic gains during the 2026 midterm elections. California’s new map is expected to cancel out Texas’ gains.

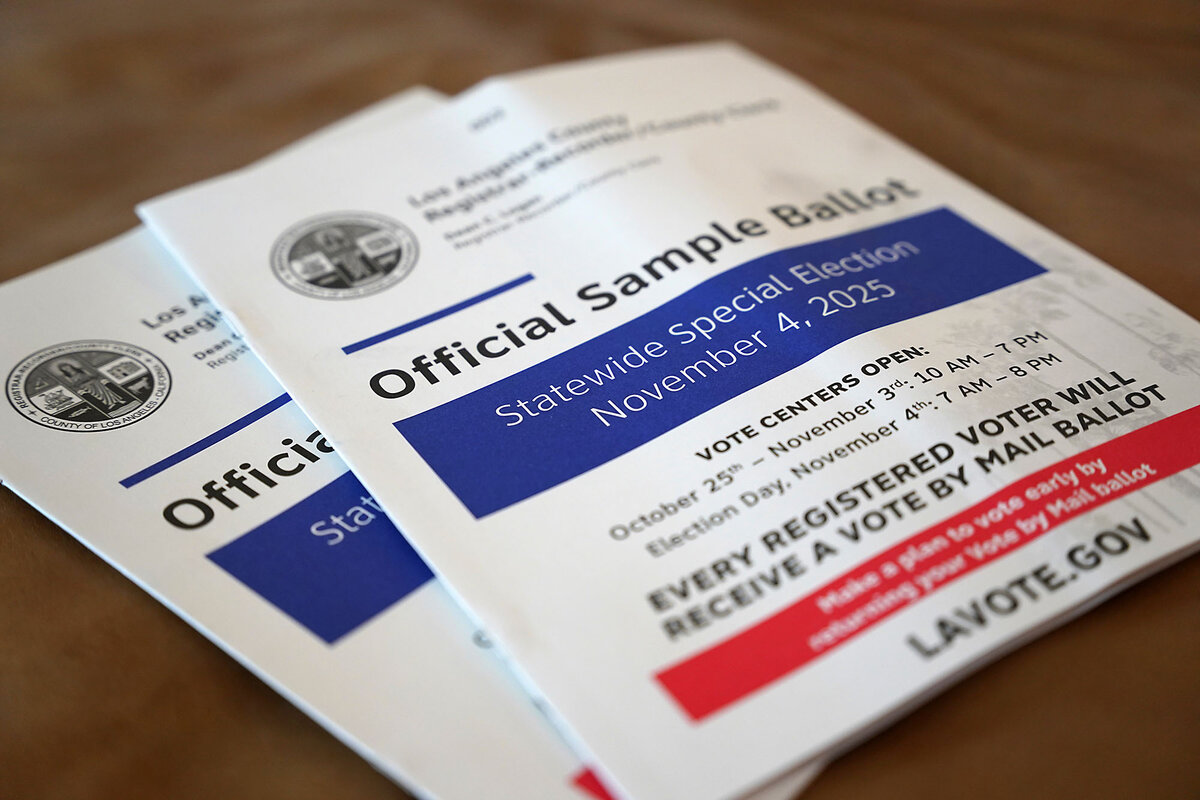

The Texas Legislature simply drew up and passed new districts. But California’s plan, which involves temporarily sidelining its independent redistricting commission, needs voter approval Nov. 4.

With the GOP holding just a six-seat majority in the House, small gains for either party could be consequential. Republicans, spurred by the White House, have already redrawn maps in North Carolina and Missouri as well as Texas to try to put seven more House seats in their column. Other red states, like Kansas, Indiana, Ohio, and Utah, could soon follow suit. Democrats are looking for ways to potentially do the same in Virginia, Illinois, New York, and Maryland.

Polling shows that many Americans, in the abstract, oppose partisan gerrymandering and see it as antithetical to democracy. But support for drawing maps without regard to partisan advantage breaks down when the other side is seen as no longer playing fair. “People generally think that when the other side has violated the norm, then you have to respond in kind,” says Hans Noel, government professor at Georgetown University.

In early August, before Texas passed its new map, just over one-third of Californians said they supported the idea of redrawing their state’s congressional lines; polling released Friday shows support is now at 60%. The ballot measure has become one of the most expensive races in state history, drawing national attention and funding. Democrats have raised more than $138 million so far, compared with opponents’ $80 million.

Professor Sadhwani’s views reflect a broader sense here that extreme partisanship is forcing bad choices onto voters and chipping away at local power as elections become nationalized. The quick rise in Californians’ support for Proposition 50 reflects the influence of national political forces and dollars that fuel the country’s partisan divide. And critics say it’s a vicious cycle.

“The more they gerrymander, the less competitive the districts are, the less important the individual voters are,” says Chad Peace, legal adviser to the Independent Voter Project, which advocates for nonpartisan election reform.

Local politics turn national

The redistricting race illustrates a new maxim, says Professor Noel: All politics are no longer local. Because political power at the national level is directly tied to a state’s congressional maps, he says, “national politics is just unavoidable now at the state level.”

That’s true in California, where a recent poll shows 75% of those who plan to vote yes on Proposition 50 say they’re doing it to oppose President Trump. In that same CBS News/YouGov poll, nearly two-thirds of voters, including Republicans, say they believe the president has treated deep-blue California worse than other states.

Democrats make up less than half (46%) of California’s registered voters, while about one-fourth (24%) are Republicans. The bulk of remaining voters list no party preference. The state’s existing congressional makeup already skews toward Democrats, who hold 43 of the state’s 52 House seats, plus both Senate seats. The Proposition 50 map tilts five more districts toward Democrats.

Republican Rep. Vince Fong, who represents a central California district, calls the new map a “power grab.” Gov. Gavin Newsom, he says, is eliminating the voice of rural communities by adding them to urban districts – all in pursuit of his own political ambitions (Governor Newsom has confirmed that he will consider a White House run in 2028).

Alfredo Sosa/Staff

Alfredo Sosa/Staff

Ventura County GOP Chair Richard Lucas says views of conservatives like him are effectively being silenced. Despite being born and raised in California, he says, he feels unwelcome by the state’s Democratic supermajority – and Proposition 50 would make it worse.

“Two wrongs don’t make a right,” he says.

If Proposition 50 passes, it will be even easier for blue states and red states to paint each other as “the enemy,” says Professor Noel. “And it makes it harder to think about a presidential campaign that’s really about trying to reach all 50 states, or a party that represents all 50 states.”

A California “rethink”

California is one of eight states that have independent commissions tasked with drawing congressional districts. In 2008, voters approved the Citizens Redistricting Commission by a narrow margin: 51% to 49%. Initially, the commission drew state legislative districts. Congressional districts were added two years later, when it also survived a repeal, with 60% voting to keep it.

“Californians rethink things all the time,” says Professor Sadhwani, who teaches politics at Pomona College. They approved the commission the same year that President Barack Obama won a sweeping victory campaigning on a message of “hope,” she adds. “If in 2025, Californians aren’t feeling quite so hopeful, it’s OK for them to revisit how they want to engage nationally.”

The current ballot proposal is tailored to the moment; it is explicitly tied to Texas’ redistricting and sunsets with the 2030 census, when the independent commission will resume its authority.

Paula Ulichney-Munoz/AP

Paula Ulichney-Munoz/AP

With those guardrails in place, “Prop. 50 is a reasonable measure that allows voters to both support independent redistricting and make a decision to stand up to this administration,” says Rusty Hicks, California Democratic Party chair.

Representatives should consider their constituents first and party second, says Mr. Peace of the Independent Voter Project. A conservative representative might even help the state work with Republican leadership, he adds. But some states are viewed as synonymous with their dominant political party, as California is with Democrats and Texas with Republicans.

“It’s a sad state of affairs,” he says, “that we’ve kind of interchanged the two issues.”

A winner-take-all system

The impact of gerrymandering on democracy can be corrosive, says Mr. Peace. With diminished competition, political parties become less responsive to voters, which leads to less engagement. “And actually, over the long term, that’s why you see people have less and less confidence in either party,” he says.

Experts suggest structural reforms could fix these challenges. Multimember districts, which would have multiple lawmakers representing a larger area, are one way to eliminate the inherent problems in redistricting and to try to create “fair” maps, he says.

Still, the same two-party system that is driving the current division has in the past supported cooperation, with periods of bipartisan lawmaking, says Professor Sadwhani, who hopes the parties can once again find middle ground.

“If no one likes this kind of gerrymandering and redistricting, let’s do away with it as a nation,” she says. “And the way to do that would be to pass independent redistricting commissions in all 50 states.”

Deepen your worldview

with Monitor Highlights.

Already a subscriber? Log in to hide ads.

Independent maps, says Professor Noel, are “state-of-the-art for good government recommendations.” But it didn’t take long, he says, for the parties to realize that surrendering control of the redistricting process has a cost at the national level, “and what seemed like an innocuous idea before, now is in the way.”

Monitor staff writer Simon Montlake contributed reporting to this story from Bakersfield, California.