Trump rescinds EPA’s ability to regulate greenhouse gases. What’s the impact?

President Donald Trump and Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lee Zeldin on Thursday ushered in a new era of climate regulation, effectively rescinding a 16-year-old foundation for federal policies to reduce emissions of heat-trapping gases such as carbon dioxide.

The White House says the move will unshackle a needlessly regulated energy sector, though many climate scientists see the step as undercutting action on an urgent priority for the United States and the world.

Since 2009, what’s known as an “endangerment finding” by the EPA has classified greenhouse gases (GHGs) as a threat to public health. In turn, that designation has served as a legal basis for emissions regulations. In undoing it, Trump administration officials argue the endangerment finding stood on shaky legal ground.

Why We Wrote This

President Donald Trump and his team held a “Clean, Beautiful Coal” event this week and are rescinding a rule that enables the EPA to regulate greenhouse gases. But the moves come as renewable energy sources including solar are increasingly in demand.

Opponents of Thursday’s action will appeal, and courts will ultimately play a key role in deciding. Both sides agree the stakes are high.

“It has the broadest impact on EPA’s legal authority, this agency that literally has one job, to protect human health and the environment,” says Meredith Hankins, the federal climate legal director at the Natural Resources Defense Council, an international environmental advocacy group. “They are just walking away from that responsibility.”

Mr. Zeldin, in announcing the reversal, said “The Trump EPA is strictly following the letter of the law, returning common sense to policy, delivering consumer choice to Americans and advancing the American dream.”

Unless blocked in court, the move represents the most aggressive rejection of climate change policies by the Trump administration thus far. It also comes as renewable energy sources are increasingly competitive in price – and popular even among Trump voters – compared with coal and other fossil-fuel energy sources.

Recent polls show strong Republican support (61% in a Pew Research Center survey) for solar energy farms, alongside other energy sources, amid concerns about high electricity costs. The economy has been continuing to move away from fossil fuels, with GHG’s declining by about 1% a year since 2007, according to the Rhodium Group. The Trump policy changes, while not erasing that trend, may slow it considerably.

The administration sees the rollback as a boost to the economy, saying the endangerment finding is “unnecessarily expensive.” Cars are one key sector that will be affected, because the finding served as the legal foundation for regulating vehicle greenhouse emissions under the Clean Air Act.

Jonathan Ernst/Reuters

Jonathan Ernst/Reuters

The decision, White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt said at a news briefing this week, will save the American people $1.3 trillion in “crushing regulations.” She also said the savings would include reduced costs for new vehicles of around $2,400 for “popular light duty cars, SUVs, and trucks.”

The endangerment finding is also the foundation for regulating coal and gas power plants and the methane levels produced by both the oil and gas industries.

Thursday’s rollback comes a day after President Trump, Mr. Zeldin, Energy Secretary Chris Wright, and Interior Secretary Doug Burgum met at the White House, where Mr. Trump hosted a “Clean Beautiful Coal” event, casting the coal industry as pivotal to U.S. energy production going forward.

Mr. Trump signed an executive order directing the Defense Department to prioritize long-term, on-demand power purchases with coal-based power plants for future military installations.

Efforts that unraveled the endangerment finding

Last July, the Heritage Foundation released a policymaker memo titled “Reversing the EPA’s Endangerment Findings on Greenhouse Gases.” Authors Kevin Dayaratna and Diana Furchtgott-Roth argued that it is inconclusive whether GHGs harm human health.

“The critical question is whether [carbon dioxide], a component of the ambient air, which is crucial for life on Earth, can be considered ‘air pollution,’” the report’s analysis reads. “The answer is ‘No.’ The Clean Air Act was not designed for the regulation of such essential components of the air that humans and animals breathe.”

The backing for the Trump administration’s argument supporting the reversal of the endangerment finding comes from an Energy Department report, “A Critical Review of Impacts of Greenhouse Gas Emissions on the U.S. Climate,” which has been used to justify diminishing the credibility of the rules precedent.

The overwhelming scientific consensus is that climate change is occurring, is the result of human activity, and poses severe risks for ecosystems and the human economy. The Trump administration’s report reflects the conclusions drawn last summer by a working group of scientists outside that consensus, formed by Energy Secretary Wright. Group members John Christy, Judith Curry, Steven Koonin, Ross McKitrick, and Roy Spencer held closed-door meetings to produce their sweeping report.

The EPA’s rationale for striking down the endangerment finding is based on the report’s suggestion that GHG regulations have minimal climate impact.

“The report was harshly criticized by many scientists, including the National Academy of Sciences, which put together a very detailed report that basically showed the Department of Energy report was completely wrong,” says Michael Gerrard, an environmental law professor at Columbia University.

Rod Lamkey, Jr./AP/File

Rod Lamkey, Jr./AP/File

On Jan. 30, U.S. District Judge William G. Young of Massachusetts ruled that the panel’s meeting was illegally convened, violating the 1972 Federal Advisory Committee Act’s transparency requirements. The panel violated the act, the judge ruled, by not opening its meetings to the public.

Judge Young, first appointed in 1985 by President Ronald Reagan, declared: “These violations are now established as a matter of law.”

What’s next for climate regulation?

The rescission of the endangered finding is expected to wipe clean most U.S. policies geared toward reducing emissions, starting with emissions standards for trucks and cars.

States, environmental groups, and industry stakeholders are expected to appeal in court against the administration’s move. The pathway for challenging the repeal starts with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, and could make its way to the Supreme Court – a process that could take years.

Deepen your worldview

with Monitor Highlights.

Already a subscriber? Log in to hide ads.

The EPA’s endangerment finding had its legal roots in a 2007 U.S. Supreme Court ruling, Massachusetts v. EPA. The court has become more conservative in the intervening years, setting up a potential swing against the tenor of its prior ruling, Professor Gerrard says.

If the issue reaches the Supreme Court, oral arguments might be influenced by the 2022 decision in West Virginia v. EPA, which established that, under what legal scholars call the “major questions doctrine,” the EPA’s authority to control emissions is limited. The ruling holds Congress, not agencies, responsible for making major policy decisions. Professor Gerrard says that if the case is won on those grounds, it could hinder a future president from reversing the current administration’s action – unless Congress provides that authority.

A year after LA wildfires, slow recovery but ‘a feeling of hope’

In the early morning hours of Jan. 8 last year, Marisol Espino lost the home she shared in Altadena with her father, child, sister, and sister’s children to the Los Angeles wildfires. Since then, she moved at least 10 times before finding an apartment where she could stay for a little while. Now she spends hours each day getting her son to and from school. Her old neighbors, she says, remain close, even if they are scattered.

But “we kind of still feel stuck,” she says. “A lot of us can’t even believe it’s been a year because a lot of us feel like we haven’t made progress.”

Her sentiment is shared in Pacific Palisades, another Los Angeles community that was devastated. “There’s a little frustration that [recovery is] not faster, but there’s also recognition from previous nearby experiences that this takes five years or more,” says Patrick Healy, a retired LA newscaster turned Palisades historian.

Why We Wrote This

Wildfires devastated LA-area communities about a year ago. There are some signs of recovery, but many residents remain uncertain about whether, or when, they will be able to rebuild their homes.

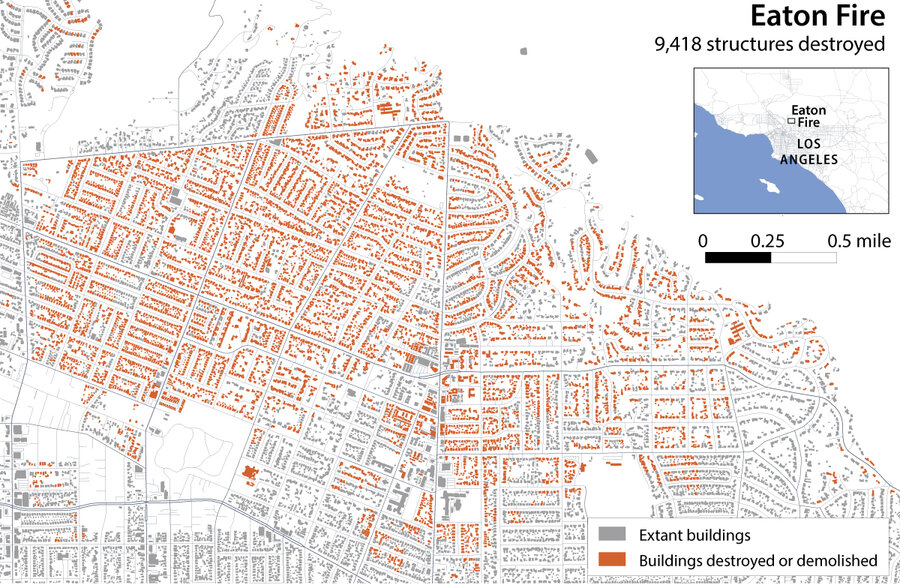

With property and other financial losses estimated between $95 billion and $164 billion, the Eaton and Palisades wildfires are the most costly disaster in the LA area’s history. Beginning Jan. 7 and burning for more than three weeks, the fires killed 31 people, destroyed 13,000 homes mainly in Altadena and the Pacific Palisades, and left thousands more uninhabitable. An October report showed about 80% of Altadena residents and 90% of Pacific Palisades residents were not living in their homes.

SOURCE:

SOURCE:

Gallagher Re, map data from OpenStreetMap

The fires came amid an insurance crisis, with carriers pulling out of high-risk areas over the last few years and forcing many homeowners onto a state-run plan that was more expensive for less comprehensive coverage. The statewide gap in private insurance coverage for single-family homes is estimated at up to $1.3 trillion. In many cases, residents’ decisions to rebuild may be determined by whether they had insurance, and if their coverage pays enough for them to stay in one of the nation’s most expensive real estate markets.

Both Altadena and Pacific Palisades have deep roots and homeowners who have lived there for decades – many of whom could not afford to buy into their neighborhoods at today’s rates. Survivors also understand that some of their neighbors may not be interested in a years-long rebuild, and that selling an empty lot could bring a substantial windfall.

Still, some optimism is spreading in each community as businesses begin to reopen and some building gets underway.

“Every day I go and I see a new house going up,” says Veronica Jones, president of the Altadena Historical Society. “In that state of recovery, there’s a feeling of hope … It’ll be not the same, of course, but we will be Altadena.”

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff/File

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff/File

Historic change

Residents in Pacific Palisades and Altadena are frustrated by a lack of clarity regarding who qualifies for financial assistance, what resources are available to homeowners and renters, and by the malaise of loss and displacement.

“This is by far the single most significant event in the century since the [Pacific Palisades] was founded,” says Mr. Healy, secretary of the neighborhood’s historical society.

The fire destroyed every essential community element: homes, schools, most businesses and churches “just disappeared,” he says.

SOURCE:

SOURCE:

Gallagher Re, map data from OpenStreetMap

In both areas, residents have expressed concern that building back might erase the neighborhoods’ distinct characters. If too many properties go to developers, they argue, the focus will be on profit, not spirit.

“I’m all about things getting better and looking better and being better for the community,” says Ms. Espino. “I don’t want it to be better and not affordable for us who were there before, and we just permanently get displaced and essentially shoved out of our community that was ours.”

Ocean Development and Black Lion Properties – two developers active in the recovery – did not respond to requests for interviews.

“A lot of human stuff”

A survey by the Department of Angels – created by the California Community Foundation and Snap founder Evan Spiegel to help residents affected by the fires – shows just over one-third of survivors said they would rebuild no matter what. Two-thirds of people whose homes were a total loss said out-of-pocket costs are an obstacle, and about one in five plan to sell their lot and move on.

A handful are back in rebuilt homes. Many are still trying to figure out how to bridge the gap between temporary housing and the years it may take to piece together funding, find a contractor, and complete construction. At the same time, they are managing jobs, families, school, and the trauma of disaster.

“It’s not just a real estate project,” says Bea Hsu, president and CEO of the nonprofit Builders Alliance. “There’s a lot of human stuff going on here that is very real.”

Builders Alliance is connecting fire-impacted homeowners with homebuilders. An online portal allows owners to search an address and find turnkey designs in a range of prices that fit the parcel.

“Their eyes really open. I think there were a number of people who, through the course of the year, had come to believe that they could not afford to rebuild. And maybe this is helping people think about it again,” she adds.

Shumin Zhen isn’t there yet – she wants to rebuild the condo she lost in Altadena, even though she has no idea what it will cost or how she’ll get the money to do it. She and her husband found temporary housing nearby in a Pasadena apartment complex for seniors.

Ms. Zhen’s story underscores the difficulties of recovery. She has tried to use publicized resources, like mortgage assistance, but was turned down. Her insurance policy for additional living expenses expires in January, so she’ll have to pay rent on top of her mortgage.

SOURCE:

SOURCE:

State of California, California Department of Insurance, California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection

The median loss for survivors – those who lost their homes and those whose homes were damaged – is $200,000. Net losses for more than half of them exceed their annual income.

Many lawsuits have been filed over both fires. In the Palisades and Malibu, homeowners are suing state and city agencies, claiming a mismanaged response made damages worse. Ms. Zhen is among those who are suing Southern California Edison, forgoing settlements offered by the utility company, which acknowledges its equipment may have started the Eaton fire. The offer, says Ms. Zhen, would be a “huge loss” for her.

Deepen your worldview

with Monitor Highlights.

Already a subscriber? Log in to hide ads.

Meanwhile, she says, she is changed by the fires.

“Life is not about stuff,” she says. “Life is about happiness and health.”

EPA’s new clean-water rules: What a rancher, builder, and scientist say

The Environmental Protection Agency is proposing to reduce the number of lakes, streams, wetlands, tributaries, and other waterways covered by the Clean Water Act, which regulates the amount and type of pollutants allowed in bodies of water. By some estimates, as much as 55 million acres of wetlands will no longer be subject to the law.

Advocates for greater protections say broader regulations are necessary to protect public health – especially safe drinking water – and the environment. But people working in agriculture, construction, and other businesses say the regulations are burdensome and represent government overreach.

The EPA’s proposal to scale back the rule known as “Waters of the United States” is the latest of several changes reflecting the priorities of different administrations. President Joe Biden expanded the rule to include any body of water that has a significant impact on traditional navigable waterways. But a court challenge led to a 2023 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Sackett v. EPA, which struck down that change. Sackett also determined that only permanent waterways qualified for federal jurisdiction and limited the types of wetlands that qualify.

Why We Wrote This

The EPA plans to reduce the scope of an old federal law that regulates waterway pollutants. The agency’s proposal reveals how far-reaching the rules are and how they affect multiple stakeholders.

The EPA says its proposed change aligns the rule with the Sackett decision. It defines waterways subject to the rule as “relatively permanent,” and requires a “continuous surface connection” to traditional waterways. The new definition affects wetlands in particular. It’s now in a public comment period before being finalized.

Matthew Daly/AP

Matthew Daly/AP

There’s a wide range of interests in the rule. Associations including those representing homebuilders, the petroleum industry, and forest owners, plus the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, filed amicus briefs in the Sackett case arguing for reduced federal authority; support for broader protections came from environmental and conservation groups, a coalition of Indian tribes, and others.

The Monitor spoke with three people from industries impacted by the EPA proposal. The interviews are edited for clarity and length.

Stacy Woods, a research director at the Union of Concerned Scientists, who studies waterways:

[The proposal says] wetlands will have to be connected to a water body, like a river, that already falls under the Clean Water Act on the surface. And this definition completely ignores how water moves in ways we can’t always see from the surface, like through soil or underground connections.

The proposed changes don’t just focus on what waters we can see from the surface; they also limit clean water protections to what they’re calling relatively permanent waters. So, [permanent waters] are those that flow year-round, or at least during the wet season. But we know that water bodies like ephemeral or intermittent streams can create connections between other water bodies, and those temporary water features, along with that groundwater, really facilitate a water-to-water pathway that ultimately leads to our drinking water. While these proposed changes might sound like they are only targeting certain wetlands, temporary streams, and some ditches, the reality is that it puts all of our water at risk, including our drinking water.

The Fish and Wildlife Service estimated that wetlands in the U.S. provide $7 trillion in benefits each year. So, that’s to fishing, recreation, water quality, and flood control. [Our research estimates] that the 30 million acres of wetlands in the Upper Midwest alone provide nearly $23 billion in residential flood mitigation benefits each year.

Healthy wetlands can capture and store carbon where it would otherwise contribute to a warming planet. The current estimates are that wetlands track and store more than 30% of soil storage carbon on Earth. But when wetlands are damaged or destroyed, such as what we expect to happen when these protections are lessened, they can release that stored carbon as methane, carbon dioxide, or other heat-trapping gases that can accelerate climate change.

Paul Sancya/AP/File

Paul Sancya/AP/File

Roger Isom, president and chief executive of the California Cotton Ginners and Growers Association and the Western Tree Nut Association:

We do a lot of what we call tidal drainage. So, we’ll irrigate one field. There’s tile drainage underneath; it collects [the groundwater], and we move it to another field. And all of that at one point or another was in [the rule], and then another time it isn’t. And, so, probably the biggest thing is certainty. Just knowing, are we in the rule? Are we not in the rule?

We know the San Juan River, Sacramento River, the tributaries; obviously, those are in. They’re navigable waters. That’s been the base interpretation. But then we start talking about canals and drainage ditches. We’re like, well, wait a minute. When we think about navigable, those aren’t navigable.

We had hoped that the [Sackett] decision was going to give us that certainty. [The EPA proposal] is the rule coming out of that. So, we hope [this proposal will offer certainty]. But we’re not going to know until the next administration and see what they might do with it.

We’ve changed our practices to make sure we don’t exceed or cause problems in the river. For example, a few years ago, we had [the insecticide] diazinon show up in the San Joaquin River, and through the Irrigated Lands program, we were able to find the growers, find out what happened, and change some practices. And we haven’t had that issue since that time. So, we definitely change what we do because, hey, we live here, we drink the water here, we breathe the air here. And, so, it’s a balance.

On the surface, [the EPA proposal] looks like it’s addressed our biggest concerns. But we hope that it does get finalized and stays this way.

Jocelyn Brennan, interim executive director, Home Builders Association of the Central Coast in California

California is in a unique situation compared with some other states, because we do have, arguably, the most stringent environmental laws of any state. I think what our industry partners are concerned about is that the state will step in with more stringent regulations. And then it will just be a different regulatory agency that we’re dealing with, versus federal.

Builders and developers, when they’re looking at site feasibility and they see a wetland or a tributary, or some body of water, and they know that’s going to require additional mitigation, maintenance, and permitting, they’re going to keep looking for a better site. When they’re doing a constraints analysis, that’s really pretty prohibitive, because they know that it’s going to be a lot of extra time and extra cost.

In theory, [the EPA proposal] helps. It should open up additional lands for development.

Deepen your worldview

with Monitor Highlights.

Already a subscriber? Log in to hide ads.

Some other states will completely benefit from [the proposed changes], and it will be great, and reduce a lot of unnecessary regulations. We’re all for, obviously, protecting the environment. But some [regulations] are for standing water that’s there when we have a good rain, and it’s gone a week later. And, so, this makes a lot of sense to us.

California is experiencing a housing crisis. And yet, the building industry is the most regulated industry in California compared with other states. And thus, we have a housing crisis. So, any type of regulations that don’t make sense, that can be streamlined, are a tool to address the housing crisis.

Regaining a sense of place: People and culture come first after Lahaina wildfire

The historic district of Lahaina remains mostly cordoned off to visitors two years after the deadliest wildfire in the United States in more than a century. Fencing, signs, and orange blockades keep curious passersby at bay.

Next month, some activity will return when two piers are expected to reopen at the harbor. County officials say 18 vessels will resume tours and whale watches, bringing some business and jobs back to the area.

But for this island community, the push for progress is tempered by growing calls for a thoughtful, culturally sensitive recovery. The 2023 blaze that killed more than 100 people in Lahaina also leveled centuries of history.

Why We Wrote This

After the deadliest fire in 100 years of U.S. history, houses are rising from the ground once again in Hawaii. But the people of Lahaina are trying to do more than rebuild buildings – they are also trying to rebuild their culture.

Lahaina sits on sacred cultural grounds. It was once the capital of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Restoring that history, say residents and county leaders, will allow the area to reclaim its identity, benefiting generations to come.

“We’ve got to go slow,” says Ke’eaumoku Kapu, executive director of Nā ‘Aikāne o Maui, Inc. The nonprofit has been overseeing cultural monitoring of the fire clean-up. “And whatever happens here should set the standard of what happens throughout the town.”

That aspiration isn’t without challenges. County leaders and cultural advocates alike say thoughtful recovery is hinged on education and community buy-in, not to mention warding off investors hoping to scoop up property.

Cultural restoration also includes bringing back the very people who call Lahaina home. The wildfire physically separated the community’s ohana, or family, dispersing residents near and far. Outside the historic district, houses are rising from the ground once again.

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

Maui County operates a rebuild dashboard that tracks metrics such as building permit status (342 being processed; 527 issued; and 89 completed for residential and non-residential buildings as of early November). Last month, the county announced that the final truckloads of wildfire debris had been moved to a permanent disposal site, clearing the way for roadway and other restoration projects to begin.

“We could rebuild the entire town and rebuild every single structure, but if we’ve lost our people, then ... those metrics don’t matter,” says John Smith, Maui County’s recovery administrator.

Center of the Hawaiian Kingdom

Tourists likely knew Front Street as the waterfront roadway filled with shops, art galleries, and restaurants. The fire consumed it. Now, cultural advocates are on a mission to restore what visitors may not have realized: the area’s historical significance.

In the early 1800s, long before Lahaina emerged as a vacationers’ paradise, King Kamehameha declared it the capital of the Hawaiian Kingdom. A cadre of royal buildings materialized near the harbor, where multiple fishponds existed. But then Christian missionaries, whaling operations, and sugar plantations arrived and erased certain aspects of cultural history. Thirsty sugar crops also diverted water from Maui’s streams.

Gone were the town’s Hawaiian names for streets, replaced by English surnames such as Shaw and Dickenson. The fishponds disappeared as well, filled in for purposes such as a baseball field.

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

The fire took even more. It destroyed the Nā ‘Aikāne Cultural Center, home to original signed manuscripts, land awards, historical documents, and artifacts. In the aftermath, Mr. Kapu sees an opportunity to recast a vision of Lahaina that honors its past.

“Let’s just bring back the integrity of our town,” he says while standing next to a map of the Lahaina Royal Complex and cultural sites. “Our children are losing their sense of place.”

In July, Maui County officials launched a two-year, $1 million master planning process for the Complex. The project, with community feedback involved, is expected to include restoration of coastal wetlands and historical sites.

Mr. Kapu pointed out some of those sites on a recent tour of the fire-ravaged sacred space. A damaged courthouse sits near the harbor. A short walk away is a barren plot of overgrown land where a 17-acre pond called Loko o Mokuhinia existed more than a century ago. In the middle was Moku’ula, a manmade island that housed King Kamehameha III’s palace.

Even longtime residents weren’t necessarily aware of the area’s history. Earle Kukahiko, a Lahaina resident who worked for the county for 33 years, says the fire inadvertently provided an educational opportunity, including for himself.

“For me growing up, that was a park,” he says, referring to Loko o Mukuhinia. “I played ball there.”

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

But Mr. Kukahiko says he has seen minds slowly change as more residents learn about Lahaina’s history. A few months ago, at a community meeting, he watched a group of women back off advocating for rebuilding King Kamehameha III Elementary School in the same location after they heard iwi kupuna, or ancestral remains, were discovered at the site. Instead, the school will be rebuilt roughly a half mile north of its original footprint.

That kind of thought shift is crucial, Mr. Kukahiko says, as Lahaina attempts to braid its past and future in this post-fire era.

“You see what a little bit of education does,” he says.

“Place of peaceful recovery”

Up a hill from the shoreline sits a tiny-home community known as Ka La’i Ola. The Hawaiian name, a gift, means “the place of peaceful recovery.”

That’s what it seeks to be for more than 900 Lahaina residents displaced by the wildfire. The modular homes, ranging in size from one to three bedrooms, are providing interim housing for up to five years. It’s not quite temporary but not long term either.

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

The community is the product of a public-private partnership that has brought together the state, the Hawaii Community Foundation, and HomeAid Hawai’i, among other partners, in a bid to provide fire survivors stability while they navigate next steps. Roughly 90% of Lahaina residents affected by the fire were renters.

Cesar Martinez and his family were among them. Now, he’s working for the nonprofit HomeAid Hawai’i and living at Ka La’i Ola with his girlfriend and three children. They spent more than a year going from “hotel to hotel to condo,” he says, before moving into a three-bedroom modular home.

“There’s kids knocking at our door. There’s kids riding bicycles down the street,” he says, describing a renewed sense of home. “So they have [a] more community feel and a lot of friendships here.”

That sense of community reverberates from a pop-up Halloween festival situated within walking distance of Ka La’i Ola. Ukulele music greets costume-clad children, some clutching their parents’ hands as they arrive. Food trucks, an inflatable bounce house, and – of course – candy await.

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

Anthony M. La Puente II, a longtime Lahaina resident who lives in the interim housing development, attended the festival with family friends. Two years ago, he was shopping at Safeway when they called to warn him about the fire so he could get to safety. There were no other sirens or alarms.

“It’s the people of Lahaina that is Lahaina,” he says from under a white canopy tent that is filling with families. He wants their voices to be heard as recovery efforts continue.

But intentional design helps. The community features garden beds and communal barbecue areas where neighbors can gather. A ti leaf plant brightens every corner of a pod containing these tiny homes. In Hawaiian culture, the tropical shrub symbolizes protection.

“When you look around, you’ll see that it’s landscaped,” says Joseph Campos, deputy director of Hawaii’s Department of Human Services. “There are native plants here, so all to just help people find some sense of normalcy.”

Normalcy doesn’t mean forever, though. The goal is for Lahaina wildfire survivors to re-establish permanent housing.

County officials have launched a program dubbed Ho’okumu Hou that offers three housing assistance programs. Two provide financial help for homeowners rebuilding. The third program is for renters who want to become first-time homeowners – a feat notoriously difficult in this high-cost-of-living state.

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

Mr. Smith, who is shepherding recovery efforts, says the county received roughly 2,800 applications for the first-time homeowners grant. The program, which offers assistance up to $600,000, will help aspiring homeowners cover closing costs or bring down the cost of their mortgage payment.

“It is moving through the process,” he says. “We’re going to help a couple hundred people become homeowners.”

Mr. Martinez and his family hope to make that transition.

“We’re taking the classes. We’re signing up for anything possible,” he says, a note of optimism in his voice. “At the end of five years for Ka La’i Ola, we’re going to be able to purchase a home.”

Ohana spirit at work

On a breezy Saturday morning, Mr. Kukahiko – or “Uncle Earle,” as he is known – sits under a canopy strung from a makeshift bathroom. Nearby is a tool shed.

He calls the temporary dwellings, which he built where his daughter’s house once stood, his sanctuary. Mr. Kukahiko and his wife lived next door. The wildfire razed their homes, along with many of their neighbors’. Like so many others, the family now lives at Ka La’i Ola.

But you can find him here most days watering plants and holding conversations with community members.

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

“I’m here most of the time just for peace of mind,” he says.

While Mr. Kukahiko is quick to label his family fortunate, he doesn’t gloss over the reality of a nonlinear recovery. Displaced residents remain wary, wondering who is telling the truth and if the influx of disaster relief money is going to the intended purpose. They also have to beware of scams. Someone tried using his daughter’s name, he says, for wildfire-related benefits.

Deepen your worldview

with Monitor Highlights.

Already a subscriber? Log in to hide ads.

But there are other reasons to remain optimistic. Good Samaritans helped rebuild a neighbor’s house. And a local contractor whom Mr. Kukahiko coached in youth baseball has promised to rebuild his home. The handshake agreement is a nod to the ohana spirit that underpins Lahaina recovery efforts.

“That’s our people,” he says. “That’s what we do here.”

Climate money is flowing around the globe. Sometimes, corruption makes it disappear.

In September, protesters in the Philippines began taking to the streets, accusing the government of misusing billions of dollars meant for flood-control efforts.

The country of islands in Southeast Asia is one of the most climate-vulnerable nations in the world and has undertaken almost 10,000 flood-control projects in the past few years.

In some ways, the protests echoed concerns raised by demonstrators and representatives from affected countries each year at United Nations climate summits: Climate funds meant to serve the public good must reach the people most affected by climate disasters.

Why We Wrote This

Countries around the globe are spending trillions of dollars to address climate issues. The money doesn’t always reach the places that need it most, meaning some people remain vulnerable to increasingly intense storms.

As world leaders gather for this year’s COP30 in Belém, Brazil, from Nov. 10 to 21, public anger in the Philippines raises larger questions about the global issue of who pays for climate response and resilience, who benefits, and how much money is being siphoned off through mismanagement or corruption.

What were the protests about?

Previous demonstrations at COP – the annual meeting of governments that are part of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) – have called on wealthy nations to compensate developing countries that bear the brunt of emissions they did not cause.

There is opposition to climate spending: Research led by Stanford University shows that the number of countries with at least one “counter climate change organization” — such as a think tank, research institute, or foundation — has more than doubled in the past 35 years. The report’s author says the economic interests of the energy and agricultural sectors are helping to shape the movement.

Anderson Coelho/Reuters

Anderson Coelho/Reuters

Yet countries globally have committed to spending trillions to mitigate the effects of climate change.

In the Philippines, tens of thousands of people demonstrated during the week of Sept. 21, triggered by the Department of Finance’s report that corruption related to flood relief projects resulted in the loss of up to 118.5 billion Philippine pesos ($2 billion) from 2023-25. Lawmakers and officials allegedly pocketed money in exchange for contracts, while hundreds of projects intended to protect the country from flooding were never built.

Jefferson Chua, a campaigner at Greenpeace Southeast Asia, says many in the Philippines suspected corruption even before the finance department report.

“Sometimes, it’s even a running joke here that when money goes to these kinds of public projects, we all know a significant portion of that goes to the pockets of these politicians,” Mr. Chua says.

He notes a saying in the Philippines: “The Filipino spirit is waterproof.” But there is evidence of more intense and frequent storms in Southeast Asia, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. A tropical storm in late October killed seven people and forced more than 22,000 people to evacuate.

Most of the protests stopped soon after they started, when a typhoon – a weather event that causes significant flooding – hit the country Sept. 22. More protests were expected, The Philippine Star reported.

How much money is earmarked for addressing climate change?

It’s complicated, partly because it can be hard to figure out what counts as climate finance.

The UNFCCC’s definition runs almost 100 words, covering everything from cutting emissions to “enhancing resilience of human and ecological systems” and implementing the goals of the Paris Agreement to cut emissions by 43% worldwide by 2030.

About 55 countries and jurisdictions say they have or are developing climate finance tracking systems. But it can still be difficult to decipher what is climate funding and what is not.

For example, grants that help build and maintain public transportation may not explicitly be labeled as such even though they could help bring down greenhouse gas emissions from cars.

A recent UNFCCC report says global spending reached an annual average of $1.3 trillion in 2021-22, the most recent data available. That includes money going toward areas such as sustainable transport, clean energy systems, and buildings and infrastructure.

This figure includes the newly established Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage, headquartered in the Philippines. A COP resolution created it to help low-income countries most vulnerable to and impacted by climate change pay for damage caused by climate-related natural disasters. Twenty-seven countries have pledged $768 million. Payments to affected countries haven’t started.

How much of climate funding is misused?

Brice Böhmer, the climate and environment director at Transparency International, helped develop the Climate and Corruption Atlas. He says it can be hard to distinguish between mismanagement and corruption.

“Even if it’s actually corruption, it’s very hard to prove that,” Mr. Böhmer says. “Because it’s more about the intention behind the mismanagement.”

Instances of climate corruption go beyond the Philippines. In 2021, an energy company agreed to a $230 million penalty in a settlement with federal prosecutors, who charged the company in connection with a bribery scheme to advance legislation that included a $1 billion bailout for two power plants in Ohio, NPR reported. In Germany in 2023, the deputy minister of the environment was ousted after he named the best man at his wedding as chair of the national energy agency’s management board, according to Reuters.

Mr. Böhmer says a major barrier to documenting corruption is gaining access to information in countries where people who voice concerns fear retaliation by the government. He says it is important to have complaint mechanisms and protections for those who raise questions.

Deepen your worldview

with Monitor Highlights.

Already a subscriber? Log in to hide ads.

“For example, environmental defenders and whistleblowers who are bringing those cases to our knowledge are doing a job that is good for all of us,” he says. “And they are usually targeted and punished, whereas the ones that should be prosecuted are the ones doing the act of corruption.”

In the Philippines, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. has established an independent commission to investigate the disappearance of funds. The country’s interior secretary estimated that around 200 people could be indicted by an anti-graft court for government officials.

Climate money is flowing around the globe. Sometimes, corruption makes it disappear.

In September, protesters in the Philippines began taking to the streets, accusing the government of misusing billions of dollars meant for flood-control efforts.

The country of islands in Southeast Asia is one of the most climate-vulnerable nations in the world and has undertaken almost 10,000 flood-control projects in the past few years.

In some ways, the protests echoed concerns raised by demonstrators and representatives from affected countries each year at United Nations climate summits: Climate funds meant to serve the public good must reach the people most affected by climate disasters.

Why We Wrote This

Countries around the globe are spending trillions of dollars to address climate issues. The money doesn’t always reach the places that need it most, meaning some people remain vulnerable to increasingly intense storms.

As world leaders gather for this year’s COP30 in Belém, Brazil, from Nov. 10 to 21, public anger in the Philippines raises larger questions about the global issue of who pays for climate response and resilience, who benefits, and how much money is being siphoned off through mismanagement or corruption.

What were the protests about?

Previous demonstrations at COP – the annual meeting of governments that are part of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) – have called on wealthy nations to compensate developing countries that bear the brunt of emissions they did not cause.

There is opposition to climate spending: Research led by Stanford University shows that the number of countries with at least one “counter climate change organization” — such as a think tank, research institute, or foundation — has more than doubled in the past 35 years. The report’s author says the economic interests of the energy and agricultural sectors are helping to shape the movement.

Anderson Coelho/Reuters

Anderson Coelho/Reuters

Yet countries globally have committed to spending trillions to mitigate the effects of climate change.

In the Philippines, tens of thousands of people demonstrated during the week of Sept. 21, triggered by the Department of Finance’s report that corruption related to flood relief projects resulted in the loss of up to 118.5 billion Philippine pesos ($2 billion) from 2023-25. Lawmakers and officials allegedly pocketed money in exchange for contracts, while hundreds of projects intended to protect the country from flooding were never built.

Jefferson Chua, a campaigner at Greenpeace Southeast Asia, says many in the Philippines suspected corruption even before the finance department report.

“Sometimes, it’s even a running joke here that when money goes to these kinds of public projects, we all know a significant portion of that goes to the pockets of these politicians,” Mr. Chua says.

He notes a saying in the Philippines: “The Filipino spirit is waterproof.” But there is evidence of more intense and frequent storms in Southeast Asia, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. A tropical storm in late October killed seven people and forced more than 22,000 people to evacuate.

Most of the protests stopped soon after they started, when a typhoon – a weather event that causes significant flooding – hit the country Sept. 22. More protests were expected, The Philippine Star reported.

How much money is earmarked for addressing climate change?

It’s complicated, partly because it can be hard to figure out what counts as climate finance.

The UNFCCC’s definition runs almost 100 words, covering everything from cutting emissions to “enhancing resilience of human and ecological systems” and implementing the goals of the Paris Agreement to cut emissions by 43% worldwide by 2030.

About 55 countries and jurisdictions say they have or are developing climate finance tracking systems. But it can still be difficult to decipher what is climate funding and what is not.

For example, grants that help build and maintain public transportation may not explicitly be labeled as such even though they could help bring down greenhouse gas emissions from cars.

A recent UNFCCC report says global spending reached an annual average of $1.3 trillion in 2021-22, the most recent data available. That includes money going toward areas such as sustainable transport, clean energy systems, and buildings and infrastructure.

This figure includes the newly established Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage, headquartered in the Philippines. A COP resolution created it to help low-income countries most vulnerable to and impacted by climate change pay for damage caused by climate-related natural disasters. Twenty-seven countries have pledged $768 million. Payments to affected countries haven’t started.

How much of climate funding is misused?

Brice Böhmer, the climate and environment director at Transparency International, helped develop the Climate and Corruption Atlas. He says it can be hard to distinguish between mismanagement and corruption.

“Even if it’s actually corruption, it’s very hard to prove that,” Mr. Böhmer says. “Because it’s more about the intention behind the mismanagement.”

Instances of climate corruption go beyond the Philippines. In 2021, an energy company agreed to a $230 million penalty in a settlement with federal prosecutors, who charged the company in connection with a bribery scheme to advance legislation that included a $1 billion bailout for two power plants in Ohio, NPR reported. In Germany in 2023, the deputy minister of the environment was ousted after he named the best man at his wedding as chair of the national energy agency’s management board, according to Reuters.

Mr. Böhmer says a major barrier to documenting corruption is gaining access to information in countries where people who voice concerns fear retaliation by the government. He says it is important to have complaint mechanisms and protections for those who raise questions.

Deepen your worldview

with Monitor Highlights.

Already a subscriber? Log in to hide ads.

“For example, environmental defenders and whistleblowers who are bringing those cases to our knowledge are doing a job that is good for all of us,” he says. “And they are usually targeted and punished, whereas the ones that should be prosecuted are the ones doing the act of corruption.”

In the Philippines, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. has established an independent commission to investigate the disappearance of funds. The country’s interior secretary estimated that around 200 people could be indicted by an anti-graft court for government officials.

She lost her husband, then LA fires took her home. How will she shape her future?

The women on stage line up and bow to applause, celebrating a moment of triumph. These dancers from Westside School of Ballet have completed their summer showcase, eight months after dozens of families at the school lost their homes in the Los Angeles wildfires.

Connie Bell glides out to center stage with the rest of her cohort, beaming with joy and relief. She stands with perfect posture, her hair pulled into a neat bun, wearing a forest green leotard and matching mesh skirt that floats when she moves.

Ms. Bell has been dancing her way through heartache. In December, her husband died after a long illness. A month later, the Palisades fire incinerated their Malibu home. She and Ed had been together for 45 years and raised a family in that little house at the edge of the Pacific Ocean.

Why We Wrote This

The LA wildfires forced thousands into sometimes overwhelming decisions on how to rebuild their lives. For 10 months, Connie Bell has shared her journey with us. Widowed a month before fire destroyed her home, she is embracing possibilities both exhilarating and daunting.

Now, as she puts it, she is back where she was as a young adult. That was the last time she was on her own, with no place she called home, no family or career to drive her decisions, with limited resources and unlimited choices.

Ali Martin/The Christian Science Monitor

Ali Martin/The Christian Science Monitor

The stakes are high, financially and emotionally. The loss of the house comes with deep sadness; rebuilding may be out of reach.

Thousands of people, like Ms. Bell, have been confronting the same decisions: sell or build; forge a new life or try to reclaim the old. The Pasadena and Altadena wildfires caused unprecedented loss in the Los Angeles area: more than 16,000 structures destroyed, three-fourths of which were homes.

Recovery is slowly getting underway across the county. Of about 4,500 applications, fewer than 1,500 building permits for fire-gutted sites have been issued by LA County and cities impacted by the fires: Los Angeles, Malibu, and Pasadena.

The labyrinth of housing, permits, government benefits, and insurance payouts is daunting. But for some, the destruction has also created a clearing – an opportunity to reevaluate and reset. Ms. Bell is taking it.

She has discovered that heartbreak and joy can coexist. Even when a person is grieving, she says, “there also are times to laugh and be alive and have joy. Those things don’t go away.”

Ali Martin/The Christian Science Monitor

Ali Martin/The Christian Science Monitor

January: “Just Connie”

On January 7, with hurricane-force winds driving fire toward the coast and smoke blacking out the sky, Ms. Bell grabbed just a few things: Sirus the family parrot, enough clothing for an overnight stay, and her ballet slippers.

She had lived most of her life in the small oceanside city, where wildfires and evacuations come with the landscape. “I didn’t really feel like I was in any danger, but I just felt like staying wasn’t the right thing for me to do,” she says.

Nearly 250,000 people were under evacuation orders that night, including Ms. Bell, who took refuge with her daughter and son-in-law in LA. By morning, everything was gone: clothes, furniture, photos, mementos – all the evidence of her family's life together perched on the edge of the sea.

With everything upended, she found structure and purpose in the ballet studio. Two days into the fires, Ms. Bell was back in class.

Ballet, she says, “sort of saved me.”

Ali Martin/The Christian Science Monitor

Ali Martin/The Christian Science Monitor

She has been dancing since childhood, through college, then professionally and as a ballet teacher. Today, she takes adult classes at Westside, in Santa Monica.

“In that room, she is just Connie,” says Charlie Hodges, her instructor. Being happy and complete in the studio, he adds, showed her that she could be those things elsewhere.

February: Home for now

A few weeks after the fires were contained, Ms. Bell has moved into a condominium that her daughter owns in Santa Monica. She is staying there with Sirus and a bulldog named Otis who made his way into Ms. Bell’s care after his owner died unexpectedly. She and the dog relate to each other, she says.

What she lacks in stability, she makes up for with resolve. Ms. Bell is ready to embrace a new chapter and sell her property. She is not alone. In the first six months after the fires, a surge of lots hit the market: more than 170 were sold in Altadena, compared with six in the first half of 2024. In the Palisades, it was 94; one the year before.

Ms. Bell’s reasons for selling are mostly financial. In this part of California, where property values and cost of living are among the highest in the country, she could make enough from the empty lot to retire in modest comfort.

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

And the thought of rebuilding without Ed feels like too much. Of the house, she says, “I just don’t have any more room for that.”

The days are stacked with checklists, phone calls, and paperwork. Her lot needs to be cleared of debris, and there are codes and filing deadlines to piece together. The trust for her estate burned, so she needs to track that down.

Amid those tasks, there is also delight: Allegra, her daughter, is having a child soon – Ms. Bell’s first grandchild.

She is creating her plan by focusing on what she loves. “I’m refreshing myself,” she says, “and I hope that I can be happy. I want to be happy.”

March: Sunshine and rainbows and realism

In late March, Ms. Bell is still waiting for a sofa to be delivered – the missing piece in a living area that’s starting to feel like home with a fluffy white rug, round metal coffee table, and Otis sprawled on the floor. Sirus squawks from his large cage.

She is balancing familiar habits – like ballet – with the newness of recovery. Her resources are limited, but not her persistence.

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

“There’s confidence that whatever she gets hit with, she’s gonna have the strength and the intelligence, the creativity to prevail,” says Beth Friedman, a longtime friend.

Built in 1946 on an iconic stretch of California waterfront, the house she shared with her husband was a far cry from the celebrity mansions that Malibu is known for today. The income she made as an Airbnb superhost helped pay the costs that come with waking up to ocean waves and dolphins.

Ed and Connie bought the house in 2002, when their two children were not yet teenagers. For a time, the four of them shared its one bedroom, their beds lined up side-by-side like Goldilocks and the Three Bears, says son Colborn.

The close quarters inside were offset by an expanse of sun and ocean outside. The house hovered over sand on support beams lapped by the ocean tide. It was, Colborn says, “a perfect place.”

Protecting it was a priority. Ms. Bell is properly insured, unlike thousands of homeowners who have been caught in the state’s insurance crisis. Between 40% and 80% of homes lost in the wildfires are underinsured, according to a state agency. The largest insurers have been pulling out of California for the last few years due to increasing environmental risks and the rising costs of rebuilding. Many homeowners have been forced onto the state’s FAIR plan, a syndicate of companies required to offer fire policies to homeowners left behind by the traditional marketplace. Those policies are more expensive and offer limited coverage.

Courtesy of Connie Bell

Courtesy of Connie Bell

Ms. Bell’s insurance covers three years’ worth of living expenses, plus a payout for the 800-square-foot house. Selling the lot comes with security and retirement. Rebuilding – which could net her more if she sold later – would take everything she has plus some. It would also take years of managing building codes and construction details.

Yet selling comes with unknowns. What will the glut of lots do to the value of her land? The longer it sits, the more her imagination fills in the property, edging out the financial realities of rebuilding.

Before the ruins are cleared, she returns to the place that framed her life and loves for 23 years.

Ms. Bell finds poetry in the wreckage, pointing out the warped roofing panels that look like handkerchiefs and the mangled antique iron bed frame draped like a piece of lace.

Tragedy has not corrupted her view – a mix of New York realism learned from her parents, says her son, and the 1960s California hippie culture she grew up in.

“Things go on and things must continue,” says Colborn. But also, for her, “everything is kind of sunshine and rainbows. She has a multiplicity to her that is in contrast, but at the same time I think is useful.”

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

April and May: A new vision

By mid-May, her cream-colored couch is finally in place, along with end tables and a lamp. A TV hangs on the wall. Ms. Bell, Otis, and Sirus are starting to have a routine.

When grief creeps in, she focuses on what was not lost: “My husband feels like love now,” she says. “And my family and my community. Those things no one will ever take from you.”

Spring has brought some setbacks: Her neighbors’ properties have been cleared by the Army Corps of Engineers. She hired a private contractor, but the person disappeared. Worse than the $1,000 she lost is the hit to her confidence. She appealed to the county but missed the deadline to sign back up for the Corps. She didn’t know who to trust, she says, and she didn’t trust herself.

Despite that, she doesn’t languish in distress. “It’s not like I don’t see the light at the end of the tunnel. It’s just been a little bit harder getting there than it should have been,” she says.

That churning fuels more what-ifs: Late-night musings are giving shape to a new vision.

In place of an empty lot, Ms. Bell imagines building a jewel box on the water’s edge. She is in touch with an architect who specializes in buildings made of glass. The lot is too small for a family home, she says, so she’ll make it a work of art – maybe to sell, maybe not.

Her children do not agree about her change of heart. Allegra thinks she should “sell the lot as soon as possible, invest the money, and live my life,” says Ms. Bell.

Colborn, on the other hand, has pushed for a rebuild. Not only would the house create a legacy for their family, he says, but he believes the project would help his mom “realize a new lease on life.”

It already has. Ms. Bell is exploring plans and permits, which she believes will add to the property’s value. It is a business decision as well as a creative one, she says, even if she is not quite sure how she’ll pay for it. Art, in step with logic.

Courtesy of Mary Ruble

Courtesy of Mary Ruble

August and everything after: Joy in the art of it

In early August, Ms. Bell sits quietly in the garden at a Santa Monica bakery.

She and her fellow dancers wrapped their ballet showcase two days earlier. The weeks of practice deepened their camaraderie, she says, just as she had hoped. Now, she feels “wonderfully and creatively liberated.”

Her teacher, Mr. Hodges, sees someone recovering with grace and grit. “She’s not trying to recreate the life she had, but she’s trying to respond to that and build a life that’s next.”

What’s next, now, is rebuilding. Geologists and structural engineers will help Ms. Bell and some neighbors build foundations on the beach. Architects will deliver plans for her new home.

Deepen your worldview

with Monitor Highlights.

Already a subscriber? Log in to hide ads.

There is joy in the art of it, and an expectation that whatever she chooses will be right for her and for the property, “and so that’s all a beautiful thing.”

“I feel like there’s so many wonderful things to live and be and do,” she says.