Trump is trying to exert more control over elections. Will he succeed?

Throughout his political career, President Donald Trump has alleged that noncitizens are voting illegally in U.S. elections, and that Democrats are allowing or even encouraging it. In Tuesday’s State of the Union address, he declared that “cheating is rampant in our elections” and that Democrats can only win by cheating. The president has talked about “nationalizing” voting in this year’s midterms, and recently said the federal government “should get involved” in elections in Democratic-run cities such as Philadelphia and Detroit “if they can’t count the votes legally and honestly.”

There is no evidence of systemic or large-scale fraud in recent federal elections. Comprehensive audits of state voter records have uncovered only a tiny number of noncitizens, of which even fewer had actually cast a ballot. But none of this has dissuaded Mr. Trump, who has urged federal law enforcement to find and prosecute ineligible voters.

Republican allies of Mr. Trump say that greater scrutiny is necessary to detect even rare cases of illegal voting and to restore public confidence in elections. Democratic lawmakers and many experts on elections administration say it is Mr. Trump’s own rhetoric that is corroding trust in elections, and that the process has been subjected to exhaustive scrutiny since he refused to accept his defeat in 2020. (Mr. Trump has not questioned the legitimacy of the elections that he won.)

Why We Wrote This

President Donald Trump has issued orders to tighten rules around voting and demanded states turn over voter rolls. Last month, the FBI raided an election center in Georgia. Most of these moves are being fought over in court, as the fall midterm elections approach.

Election officials in Democratic-run states are reportedly bracing for potential pre- and post-election interference by the Trump administration, gaming out how they might respond if, for example, federal agents are deployed to polling centers or ordered to seize ballots if disputes arise. A senior Department of Homeland Security official told state election officials Wednesday that immigration enforcement officers wouldn’t be deployed to the polls, Politico reported.

Voters have become less trusting of elections over the past year, according to a poll by the University of California, San Diego taken between December and January. Only 60% of eligible voters expressed confidence that their midterm votes would be counted fairly, down from 77% shortly after the 2024 election, with declines across all partisan affiliations.

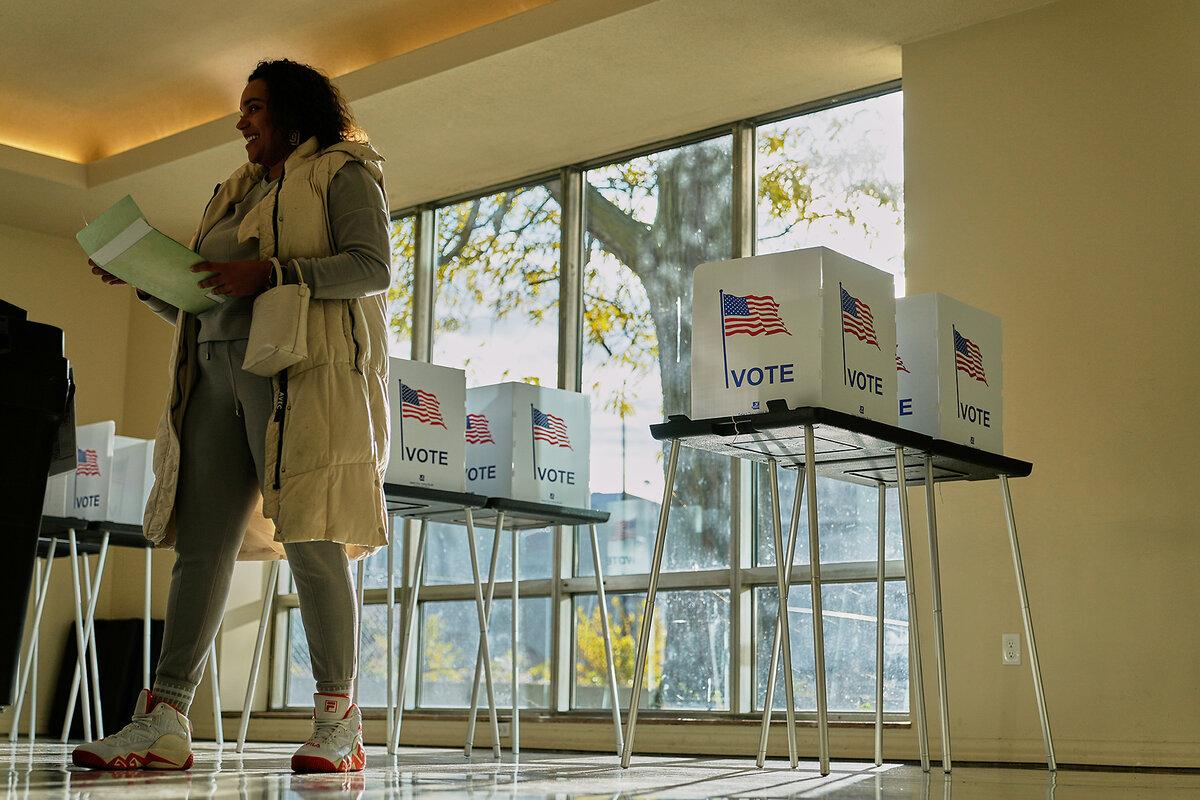

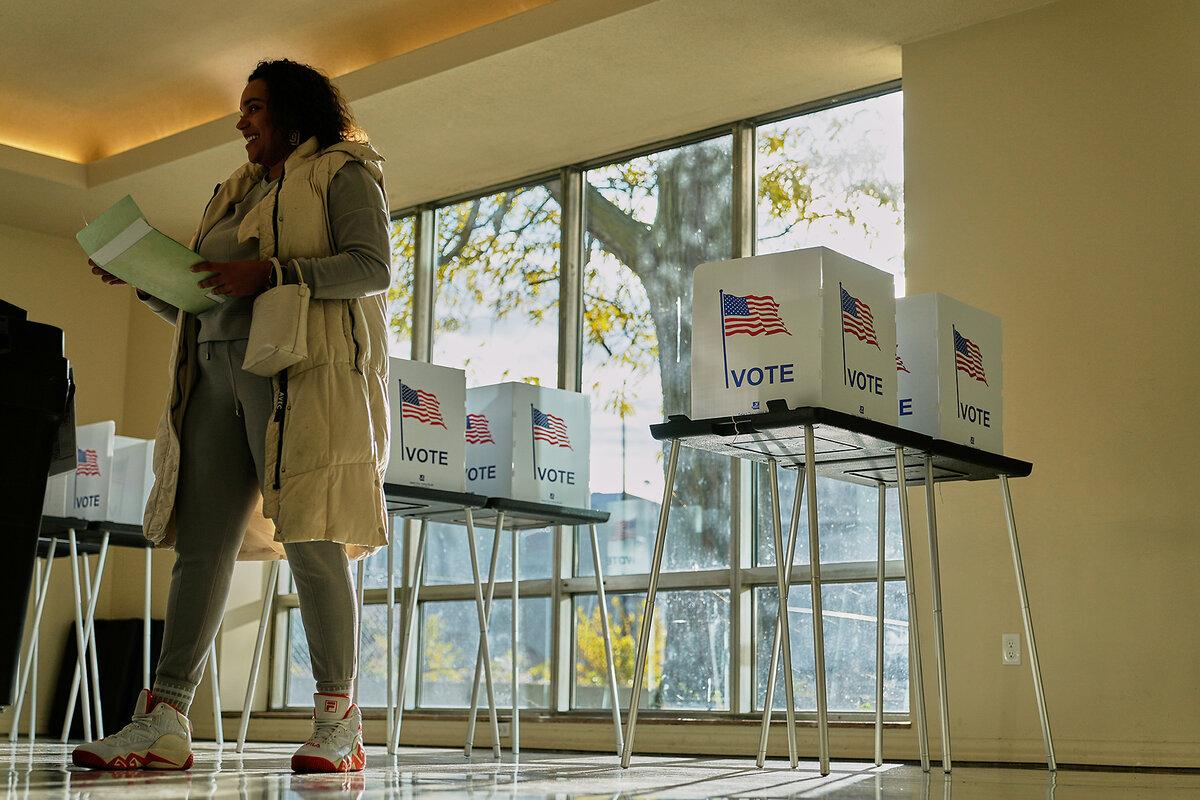

Ryan Sun/AP/File

Ryan Sun/AP/File

The Trump administration has tried to muster executive authority to dictate how elections are run, issuing executive orders and demanding that states comply. Courts have blocked most of these orders on constitutional grounds; elections are the prerogative of states, not of the federal government. Congress has also taken up GOP-written legislation that would compel states to require proof of citizenship for voter registration and would tighten voting rules. The act has passed the House but is stalled in the Senate.

But perhaps the biggest show of federal authority came last month in Fulton County, Georgia, when the FBI raided an election center and seized boxes of ballots as part of a criminal investigation into the 2020 election.

Critics say the Fulton County raid shows how far the Trump administration is prepared to go to pursue its goals. “I think it’s a test case. ... You’ve seen it over and over again in this administration: Just push the boundaries and see who’s going to stop you,” says Gilda Daniels, a law professor at the University of Baltimore who previously served in the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice. “I don’t think this is the last of these attempts.”

Why is the FBI investigating the 2020 election in Georgia?

The FBI seized hundreds of boxes of ballots, voter rolls, and other materials in Fulton County, which includes Atlanta, on Jan. 28. An affidavit submitted to a magistrate judge to secure a search warrant presented “probable cause” of criminal wrongdoing by county officials who oversaw the 2020 election. Mr. Trump lost in Georgia by a narrow margin; Fulton County went for his opponent, Joe Biden.

The allegations are familiar to Georgia election officials, who previously investigated irregularities in Fulton County. Mr. Trump and his allies failed to prove any wrongdoing in court or during multiple ballot recounts in 2020, but have kept amplifying their allegations. Some complaints are grounded in facts: Fulton County scanned some ballots twice during a machine recount. The recounts did turn up more votes for Mr. Trump, but not enough to make a difference, and state officials found no evidence of intentional misconduct.

Other claims in the affidavit have already been debunked and are sourced to right-wing activists allied to Mr. Trump. Fulton County election officials have sued, saying the raid was based on misleading information, and demanding the ballots be returned. A hearing scheduled for Friday was postponed until mid-March.

Mr. Trump’s efforts to reverse his defeat in Georgia by urging state officials to “find” him 11,780 more votes led to his indictment in 2022 in Fulton County on charges of racketeering and other allegations. The case brought by District Attorney Fani Willis was later derailed by accusations of prosecutorial misconduct and never went to trial.

Mr. Trump’s praise of last month’s FBI raid in Fulton County – which included the highly unusual on-site presence of his director of national intelligence, Tulsi Gabbard – highlights the political stakes. It speaks to Mr. Trump’s insistence on relitigating his 2020 defeat, which he still claims was rigged, and his determination to exert more federal control over elections. And it is already casting a shadow over how states prepare for this year’s midterms.

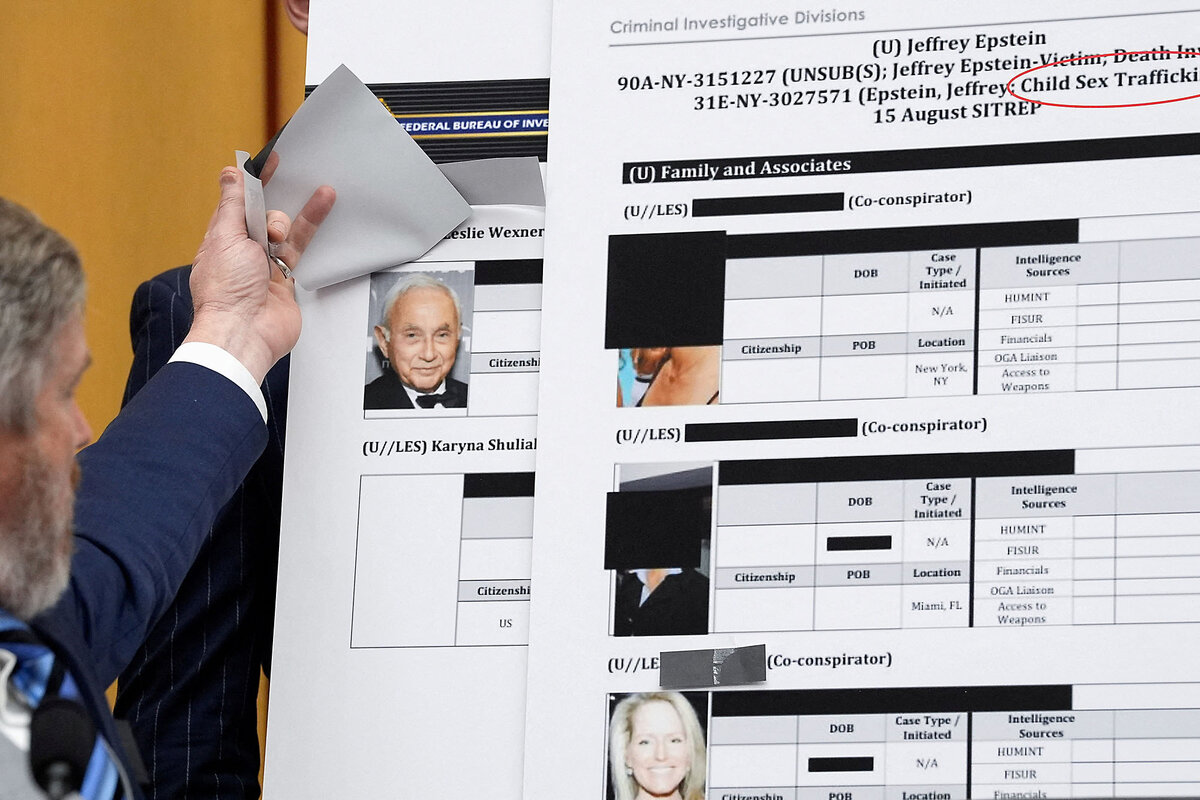

Mike Stewart/AP

Mike Stewart/AP

The seizure of ballots and other materials from Fulton County set off alarms among election officials across the United States, says Tammy Patrick, a former elections official in Maricopa County, Arizona. State laws restrict who can access sensitive materials. If they’re removed, “then you have lost all chain of custody,” she says. “This is something we have not seen before.”

Election officials take oaths to uphold state and federal laws. Going forward, “everyone is just making sure that their own statutes protect the integrity of the materials that they have ... a sworn constitutional duty to secure,” says Ms. Patrick, who is a programs officer at the National Association of Election Officials.

Why is the Department of Justice suing states to force them to submit voter data?

Attorney General Pam Bondi has asked states to submit their complete voter registration rolls to the federal government for accuracy checks, citing federal law. The administration contends that checking state voter rolls against federal databases can help uncover cases of noncitizen voting. Some states have complied, but others have declined, citing privacy laws. Democratic officials in these states have also questioned what the federal government will do with the data.

The Department of Justice has responded by suing 24 states and the District of Columbia. These states are virtually all Democratic-run, though some Republican-run states, such as West Virginia, have also refused to comply, arguing that states are responsible for running elections and already maintain accurate voter records. So far, courts have sided with the states by dismissing the DOJ’s lawsuits.

Louisiana is one of the states that has complied with the DOJ’s request. In September, Louisiana Secretary of State Nancy Landry, a Republican, announced that the state had found 390 noncitizens who had registered to vote, of which 79 had voted in past elections. “I want to be clear: noncitizens illegally registering or voting is not a systemic problem in Louisiana,” Ms. Landry said in a statement. (Louisiana has around 3 million registered voters.)

These numbers may be wrong, though, because the federal database used to cross-check voting rolls is unreliable. Utah Lt. Gov. Deidre Henderson, a Republican, said in a January statement that election officials had found the database to be “notoriously inaccurate” in flagging its citizens as ineligible to vote. (ProPublica has uncovered similar problems.) Utah’s own citizenship review of voters – it declined the DOJ’s demand to submit private voter data – found one registration of a noncitizen who had never voted.

Ms. Henderson shared her own experience: In 2022, she didn’t receive a mail ballot because the county clerk had wrongly marked her as a noncitizen during “a too-aggressive scrubbing” of voter rolls because she was born on a NATO base in the Netherlands.

Clerical errors happen, says David Becker, a former DOJ attorney who directs the Center for Election Innovation & Research, a nonprofit. But the men and women who run elections aren’t playing political games, he says. “Election officials want every eligible voter to vote and only eligible voters to vote. The most liberal Democrat doesn’t want an ineligible voter to vote, and the most conservative Republican doesn’t want to disenfranchise an eligible voter.”

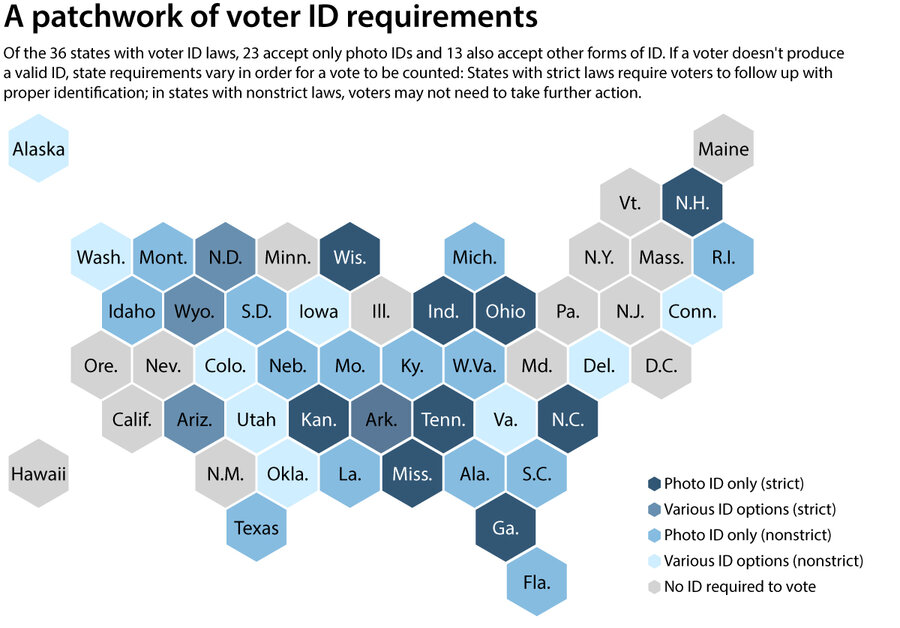

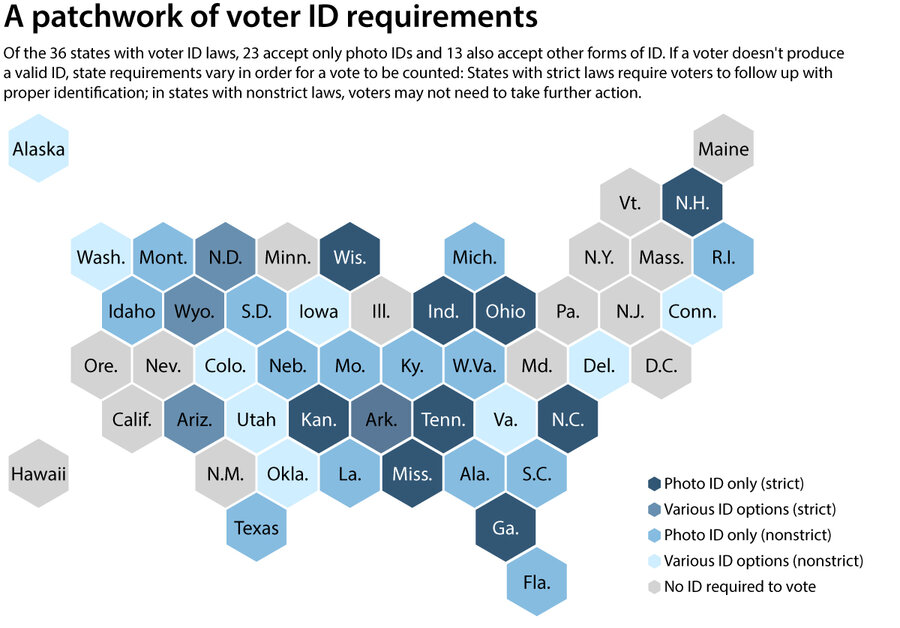

SOURCE:

SOURCE:

National Conference of State Legislatures

How could proof-of-citizenship requirements affect the midterms?

A bill that passed the House in January would require people to submit a passport or birth certificate to register to vote in federal elections, with some exceptions, and to present a photo ID when casting a ballot in person. Republicans say the SAVE America Act, which also includes provisions for sharing voter rolls with the federal government, would enhance election security and shouldn’t present a problem for eligible voters. Democratic lawmakers have opposed the bill, saying it would suppress turnout and cause hardship for citizens without proper documentation.

Matthew Germer, a governance expert at R Street, a Washington-based think tank that favors limited government, says the bill provides an upgrade of existing safeguards even if claims of widespread electoral fraud aren’t supported by evidence. “It gives people more confidence that their elections are being conducted with integrity,” he says.

But he cautions that the political rhetoric from Republicans about the need to pass the bill, which Mr. Trump echoed in Tuesday’s speech, may diminish trust in an already secure system. A majority of states already require voters to show photo identification.

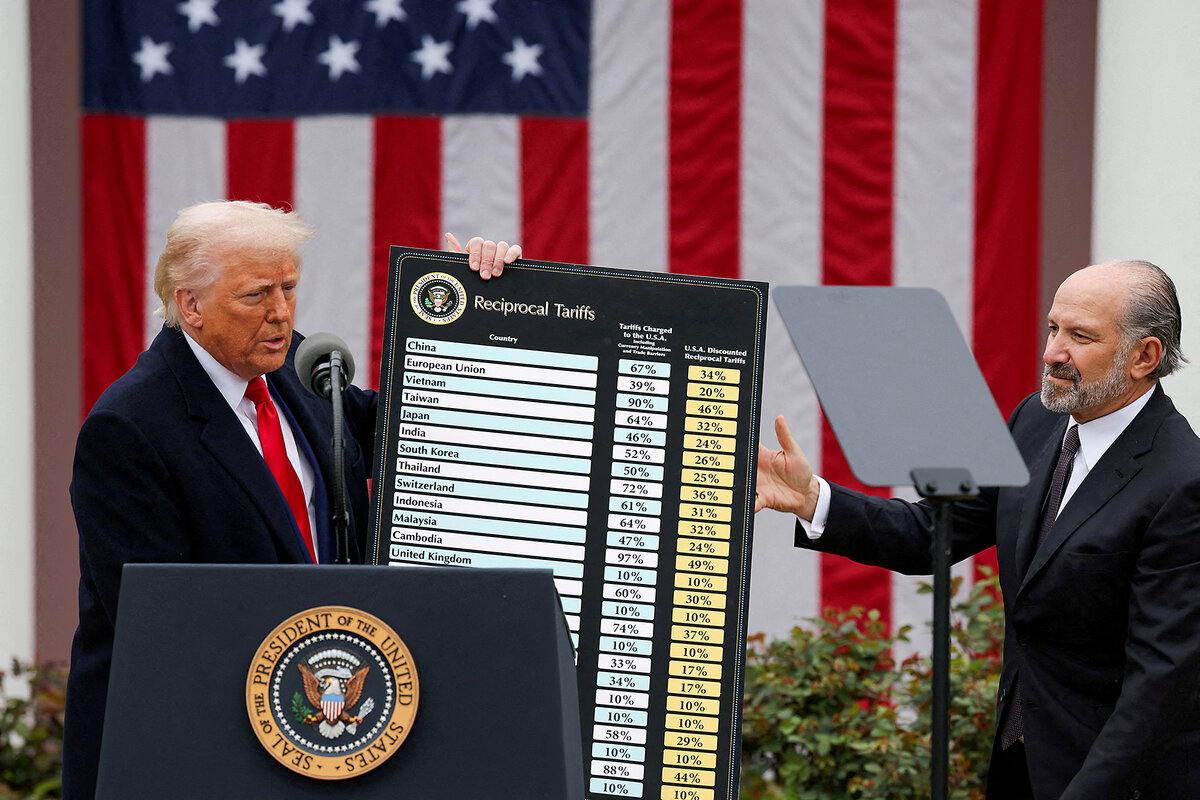

Tom Brenner/AP

Tom Brenner/AP

Republicans in the Senate lack the votes to pass the bill on their own without suspending the filibuster, a move that Majority Leader John Thune opposes. He has also quashed calls to use a “talking filibuster.”

Polls show a large majority of voters from both parties support the forms of verification in the SAVE America Act. At the same time, studies show that voter ID laws don’t always have a major effect on turnout and can motivate voters who oppose them.

Arizona passed a proposition in 2004 to require proof of citizenship to register to vote in state elections. Ms. Patrick worked on its implementation, which she calls a bumpy process. “You had people who had been voting literally for decades but didn’t have the paperwork.”

The burden fell more on older and rural voters, on people with disabilities, and on tribal members, says Ms. Patrick. She thinks the provisions in the SAVE America Act would “impact more Americans and prevent them from participating than I think people realize.”

“There’re going to be Democrats, there’re going to be Republicans, there’re going to be unaffiliated voters. It’s exactly what we saw in Maricopa County,” she says.

A survey taken last year by the Center for Democracy and Civic Engagement at the University of Maryland found that 9% of voters didn’t have ready access to documents such as birth certificates that could prove their citizenship. Roughly half of Americans hold passports.

Some GOP strategists believe stricter verification laws would confer a partisan advantage to the GOP. But the electoral coalition that backed Mr. Trump might actually be more impacted by stricter rules, says Mr. Becker.

Deepen your worldview

with Monitor Highlights.

Already a subscriber? Log in to hide ads.

Democrats are more likely to hold passports, for example. Single women, who skew Democratic, don’t face the barriers in proving citizenship as married women who changed their last names. The young and disaffected men who flocked to Mr. Trump may not have the proper paperwork on hand or be inclined to hunt it down to vote in a midterm election.

“There’s such an adherence to this false mythology about elections, coming primarily from the White House, that no one appears to be really giving thought to, ‘Hey, is this actually going to do what we think it’s going to do?’” says Mr. Becker.

Trump is trying to exert more control over elections. Will he succeed?

Throughout his political career, President Donald Trump has alleged that noncitizens are voting illegally in U.S. elections, and that Democrats are allowing or even encouraging it. In Tuesday’s State of the Union address, he declared that “cheating is rampant in our elections” and that Democrats can only win by cheating. The president has talked about “nationalizing” voting in this year’s midterms, and recently said the federal government “should get involved” in elections in Democratic-run cities such as Philadelphia and Detroit “if they can’t count the votes legally and honestly.”

There is no evidence of systemic or large-scale fraud in recent federal elections. Comprehensive audits of state voter records have uncovered only a tiny number of noncitizens, of which even fewer had actually cast a ballot. But none of this has dissuaded Mr. Trump, who has urged federal law enforcement to find and prosecute ineligible voters.

Republican allies of Mr. Trump say that greater scrutiny is necessary to detect even rare cases of illegal voting and to restore public confidence in elections. Democratic lawmakers and many experts on elections administration say it is Mr. Trump’s own rhetoric that is corroding trust in elections, and that the process has been subjected to exhaustive scrutiny since he refused to accept his defeat in 2020. (Mr. Trump has not questioned the legitimacy of the elections that he won.)

Why We Wrote This

President Donald Trump has issued orders to tighten rules around voting and demanded states turn over voter rolls. Last month, the FBI raided an election center in Georgia. Most of these moves are being fought over in court, as the fall midterm elections approach.

Election officials in Democratic-run states are reportedly bracing for potential pre- and post-election interference by the Trump administration, gaming out how they might respond if, for example, federal agents are deployed to polling centers or ordered to seize ballots if disputes arise. A senior Department of Homeland Security official told state election officials Wednesday that immigration enforcement officers wouldn’t be deployed to the polls, Politico reported.

Voters have become less trusting of elections over the past year, according to a poll by the University of California, San Diego taken between December and January. Only 60% of eligible voters expressed confidence that their midterm votes would be counted fairly, down from 77% shortly after the 2024 election, with declines across all partisan affiliations.

Ryan Sun/AP/File

Ryan Sun/AP/File

The Trump administration has tried to muster executive authority to dictate how elections are run, issuing executive orders and demanding that states comply. Courts have blocked most of these orders on constitutional grounds; elections are the prerogative of states, not of the federal government. Congress has also taken up GOP-written legislation that would compel states to require proof of citizenship for voter registration and would tighten voting rules. The act has passed the House but is stalled in the Senate.

But perhaps the biggest show of federal authority came last month in Fulton County, Georgia, when the FBI raided an election center and seized boxes of ballots as part of a criminal investigation into the 2020 election.

Critics say the Fulton County raid shows how far the Trump administration is prepared to go to pursue its goals. “I think it’s a test case. ... You’ve seen it over and over again in this administration: Just push the boundaries and see who’s going to stop you,” says Gilda Daniels, a law professor at the University of Baltimore who previously served in the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice. “I don’t think this is the last of these attempts.”

Why is the FBI investigating the 2020 election in Georgia?

The FBI seized hundreds of boxes of ballots, voter rolls, and other materials in Fulton County, which includes Atlanta, on Jan. 28. An affidavit submitted to a magistrate judge to secure a search warrant presented “probable cause” of criminal wrongdoing by county officials who oversaw the 2020 election. Mr. Trump lost in Georgia by a narrow margin; Fulton County went for his opponent, Joe Biden.

The allegations are familiar to Georgia election officials, who previously investigated irregularities in Fulton County. Mr. Trump and his allies failed to prove any wrongdoing in court or during multiple ballot recounts in 2020, but have kept amplifying their allegations. Some complaints are grounded in facts: Fulton County scanned some ballots twice during a machine recount. The recounts did turn up more votes for Mr. Trump, but not enough to make a difference, and state officials found no evidence of intentional misconduct.

Other claims in the affidavit have already been debunked and are sourced to right-wing activists allied to Mr. Trump. Fulton County election officials have sued, saying the raid was based on misleading information, and demanding the ballots be returned. A hearing scheduled for Friday was postponed until mid-March.

Mr. Trump’s efforts to reverse his defeat in Georgia by urging state officials to “find” him 11,780 more votes led to his indictment in 2022 in Fulton County on charges of racketeering and other allegations. The case brought by District Attorney Fani Willis was later derailed by accusations of prosecutorial misconduct and never went to trial.

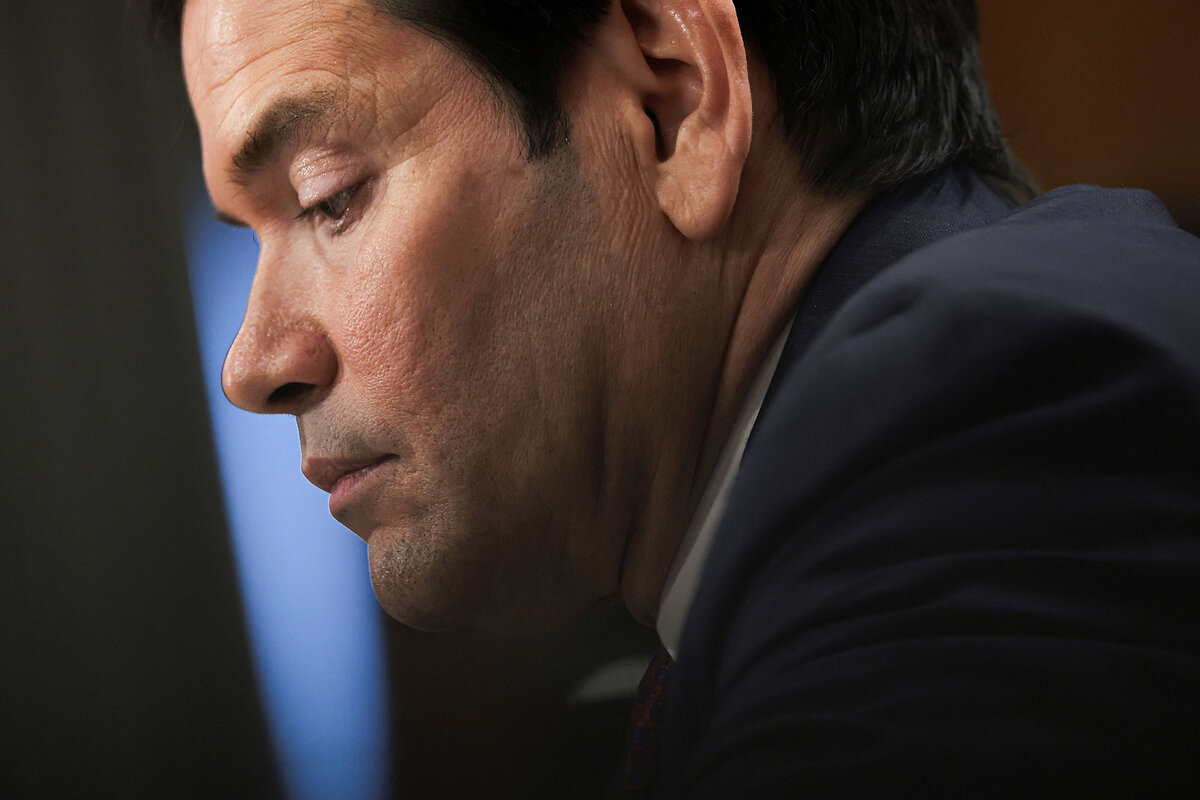

Mr. Trump’s praise of last month’s FBI raid in Fulton County – which included the highly unusual on-site presence of his director of national intelligence, Tulsi Gabbard – highlights the political stakes. It speaks to Mr. Trump’s insistence on relitigating his 2020 defeat, which he still claims was rigged, and his determination to exert more federal control over elections. And it is already casting a shadow over how states prepare for this year’s midterms.

Mike Stewart/AP

Mike Stewart/AP

The seizure of ballots and other materials from Fulton County set off alarms among election officials across the United States, says Tammy Patrick, a former elections official in Maricopa County, Arizona. State laws restrict who can access sensitive materials. If they’re removed, “then you have lost all chain of custody,” she says. “This is something we have not seen before.”

Election officials take oaths to uphold state and federal laws. Going forward, “everyone is just making sure that their own statutes protect the integrity of the materials that they have ... a sworn constitutional duty to secure,” says Ms. Patrick, who is a programs officer at the National Association of Election Officials.

Why is the Department of Justice suing states to force them to submit voter data?

Attorney General Pam Bondi has asked states to submit their complete voter registration rolls to the federal government for accuracy checks, citing federal law. The administration contends that checking state voter rolls against federal databases can help uncover cases of noncitizen voting. Some states have complied, but others have declined, citing privacy laws. Democratic officials in these states have also questioned what the federal government will do with the data.

The Department of Justice has responded by suing 24 states and the District of Columbia. These states are virtually all Democratic-run, though some Republican-run states, such as West Virginia, have also refused to comply, arguing that states are responsible for running elections and already maintain accurate voter records. So far, courts have sided with the states by dismissing the DOJ’s lawsuits.

Louisiana is one of the states that has complied with the DOJ’s request. In September, Louisiana Secretary of State Nancy Landry, a Republican, announced that the state had found 390 noncitizens who had registered to vote, of which 79 had voted in past elections. “I want to be clear: noncitizens illegally registering or voting is not a systemic problem in Louisiana,” Ms. Landry said in a statement. (Louisiana has around 3 million registered voters.)

These numbers may be wrong, though, because the federal database used to cross-check voting rolls is unreliable. Utah Lt. Gov. Deidre Henderson, a Republican, said in a January statement that election officials had found the database to be “notoriously inaccurate” in flagging its citizens as ineligible to vote. (ProPublica has uncovered similar problems.) Utah’s own citizenship review of voters – it declined the DOJ’s demand to submit private voter data – found one registration of a noncitizen who had never voted.

Ms. Henderson shared her own experience: In 2022, she didn’t receive a mail ballot because the county clerk had wrongly marked her as a noncitizen during “a too-aggressive scrubbing” of voter rolls because she was born on a NATO base in the Netherlands.

Clerical errors happen, says David Becker, a former DOJ attorney who directs the Center for Election Innovation & Research, a nonprofit. But the men and women who run elections aren’t playing political games, he says. “Election officials want every eligible voter to vote and only eligible voters to vote. The most liberal Democrat doesn’t want an ineligible voter to vote, and the most conservative Republican doesn’t want to disenfranchise an eligible voter.”

SOURCE:

SOURCE:

National Conference of State Legislatures

How could proof-of-citizenship requirements affect the midterms?

A bill that passed the House in January would require people to submit a passport or birth certificate to register to vote in federal elections, with some exceptions, and to present a photo ID when casting a ballot in person. Republicans say the SAVE America Act, which also includes provisions for sharing voter rolls with the federal government, would enhance election security and shouldn’t present a problem for eligible voters. Democratic lawmakers have opposed the bill, saying it would suppress turnout and cause hardship for citizens without proper documentation.

Matthew Germer, a governance expert at R Street, a Washington-based think tank that favors limited government, says the bill provides an upgrade of existing safeguards even if claims of widespread electoral fraud aren’t supported by evidence. “It gives people more confidence that their elections are being conducted with integrity,” he says.

But he cautions that the political rhetoric from Republicans about the need to pass the bill, which Mr. Trump echoed in Tuesday’s speech, may diminish trust in an already secure system. A majority of states already require voters to show photo identification.

Tom Brenner/AP

Tom Brenner/AP

Republicans in the Senate lack the votes to pass the bill on their own without suspending the filibuster, a move that Majority Leader John Thune opposes. He has also quashed calls to use a “talking filibuster.”

Polls show a large majority of voters from both parties support the forms of verification in the SAVE America Act. At the same time, studies show that voter ID laws don’t always have a major effect on turnout and can motivate voters who oppose them.

Arizona passed a proposition in 2004 to require proof of citizenship to register to vote in state elections. Ms. Patrick worked on its implementation, which she calls a bumpy process. “You had people who had been voting literally for decades but didn’t have the paperwork.”

The burden fell more on older and rural voters, on people with disabilities, and on tribal members, says Ms. Patrick. She thinks the provisions in the SAVE America Act would “impact more Americans and prevent them from participating than I think people realize.”

“There’re going to be Democrats, there’re going to be Republicans, there’re going to be unaffiliated voters. It’s exactly what we saw in Maricopa County,” she says.

A survey taken last year by the Center for Democracy and Civic Engagement at the University of Maryland found that 9% of voters didn’t have ready access to documents such as birth certificates that could prove their citizenship. Roughly half of Americans hold passports.

Some GOP strategists believe stricter verification laws would confer a partisan advantage to the GOP. But the electoral coalition that backed Mr. Trump might actually be more impacted by stricter rules, says Mr. Becker.

Deepen your worldview

with Monitor Highlights.

Already a subscriber? Log in to hide ads.

Democrats are more likely to hold passports, for example. Single women, who skew Democratic, don’t face the barriers in proving citizenship as married women who changed their last names. The young and disaffected men who flocked to Mr. Trump may not have the proper paperwork on hand or be inclined to hunt it down to vote in a midterm election.

“There’s such an adherence to this false mythology about elections, coming primarily from the White House, that no one appears to be really giving thought to, ‘Hey, is this actually going to do what we think it’s going to do?’” says Mr. Becker.

Texas primary sizzles as two very different Democrats face off in Senate race

Democrats in Texas are getting excited.

Ahead of the March 3 U.S. Senate primary, more people have voted early in the Democratic race so far this year than voted in the entire 2022 primary, according to VoteHub, an independent and nonpartisan political analysis website.

The contest pits Rep. Jasmine Crockett, a member of Congress from Dallas, against state Rep. James Talarico, from the Austin suburbs. Voters have been casting their ballots in record numbers, giving the party faithful hope that one of their candidates has a chance of becoming the first Democrat elected statewide in Texas in over 30 years.

Why We Wrote This

In politically red Texas, Democrats rarely have hope. But their U.S. Senate primary race features two candidates whose contrasting styles and online reach are giving the party a jolt of energy.

In one sense, these numbers are not surprising. A midterm election typically favors the out-of-power party, and the in-power party tends to suffer even more if the president is unpopular. Both factors are true here for the Republican Party and President Donald Trump. Most polls show Mr. Trump’s favorability rating has dropped to averages in the low 40s nationally, and to about 50% among Texas voters.

But the Senate race is giving Democrats extra juice this year, experts and pollsters say. With the candidates’ policy positions mostly aligned, the Crockett-Talarico contest has become a clash of styles and strategies. It’s a race that Democrats will be closely watching nationwide, because of its importance to the party’s efforts to take control of the U.S. Senate and how it embodies divisions within the Democratic Party.

“Democrats could use a few high-profile dogfights in the primary because it gins up interest,” says James Henson, director of the Texas Politics Project at the University of Texas at Austin. “We don’t know if it will generate a victory for them, but so far it’s good to ... excite the base.”

Whoever wins the primary will face off in November’s general election against the winner of the Republican primary, where four-term Sen. John Cornyn faces a tough challenge from Texas Attorney General and MAGA firebrand Ken Paxton.

Jose Luis Gonzalez/Reuters

Jose Luis Gonzalez/Reuters

“Hunger for a different kind of politics”

On a chilly Monday evening in Waco, the line to see Representative Talarico stretched around the block. Whoever wins the Democratic primary is unlikely to win here – Mr. Trump won this mostly rural central Texas county by 33 points in 2024 – but Talarico supporters packed the ornate, century-old Hippodrome Theatre.

The turnout in the Republican stronghold encouraged Oliver Santander, who attended the rally with his sister, Emily.

“I’m just happy to see everyone here,” he said. “You don’t think your voice is as loud until you get around the crowd like this.”

Mr. Talarico entered the race as a relative unknown, but he has shot to stardom following a strategy popular among recent Democratic candidates. He has courted moderate Texans, touting his Christian faith and his work across the aisle as a state lawmaker.

He has also enjoyed several viral interviews. His first major national appearance came when he appeared on Joe Rogan’s podcast in July last year and Mr. Rogan said he should run for president. More recently, CBS pulled his interview with Stephen Colbert on the Late Show off the air over concerns it would violate a Federal Communications Commission regulation on political messaging. The interview instead appeared on the show’s YouTube channel, and the controversy only seemed to attract more eyeballs: at least 6 million more views than Colbert’s quarterly average on TV.

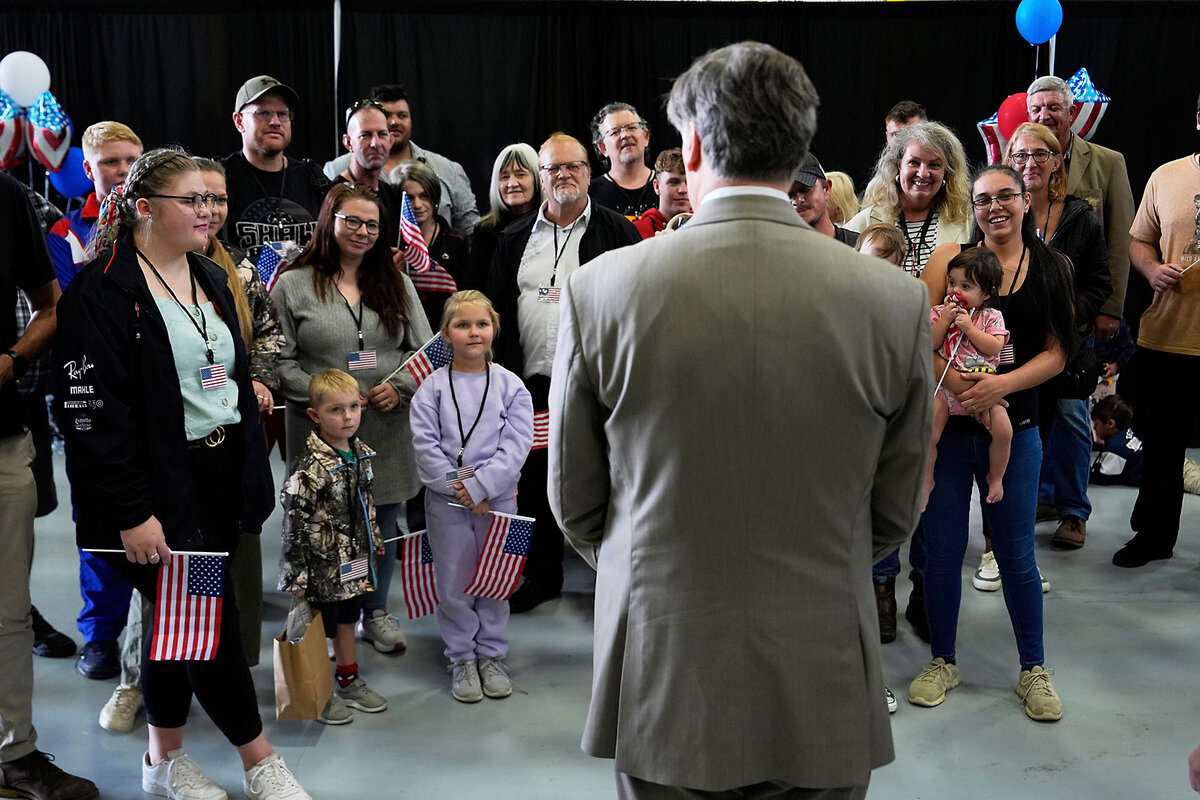

Henry Gass/The Christian Science Monitor

Henry Gass/The Christian Science Monitor

A Presbyterian seminary student, Mr. Talarico’s decision to make his faith – and his opposition to Christian Nationalism – a centerpiece of his politics has helped attract supporters. The hope among some of them lining up in the cold in Waco is that he can attract support from non-Democratic voters as well.

“I am tired of being pitted against my neighbor. I am tired of being told to hate my neighbor,” Mr. Talarico noted at his campaign event. “Across the political spectrum there is a deep hunger for a different kind of politics.”

Both Representatives Talarico and Crockett “have a lot to offer,” said Bill Purdue, a lifelong Democrat, as he waited to enter the theater.

But, he added, “a Democrat like Talarico, who comes from a strong religious point of view, would have a good opportunity to catch the ear of the many religious folks that live in Texas, particularly those that are perhaps sitting on the fence.”

Henry Gass/The Christian Science Monitor

Henry Gass/The Christian Science Monitor

“Try something new”

Mr. Talarico emphasized his calmer style and olive-branch strategy at the Waco event. “When you extend an open hand rather than a fist, you’ll be surprised how many people take that hand,” he said.

If he represents an open hand, Ms. Crockett has unashamedly branded herself as the fist in that analogy.

She entered the race in December with a national profile built through three years of aggressive, viral clashes with Republicans in Congress. Her firebrand style has enthused Democrats critical of the party’s unwillingness to take the fight to the Trump administration.

“We need someone who is a proven fighter in this moment, someone who will not back down, someone who will not fold,” she said in an interview last weekend. “My track record is clear. I have always fought for the people that I represented, and I’ve never folded.”

Ms. Crockett is not the style of candidate Democrats have chosen to run in recent top-ticket statewide races. Former U.S. Reps. Beto O’Rourke and Colin Allred – who ran for U.S. Senate in 2018 and 2024, respectively – campaigned as moderates, hoping to win over more centrist Republicans. Both lost.

While branding herself as a fighter, not a conciliator, Ms. Crockett is also running an unconventional campaign. She has spent little on campaign ads so far, and her rallies have often been pop-up events with little advance notice. She doesn’t appear to have a campaign manager or a media spokesperson. The Crockett campaign did not respond to multiple interview requests sent to a general campaign email.

These choices have frustrated national Democrats, NOTUS reported earlier this month, but her campaign says they are her best path to victory.

“We reject the DC playbook of politics as usual, because this moment — and winning — demands something different,” Karrol Rimal, a Crockett campaign staffer, told the news organization NOTUS in a statement.

This reflects a discussion national Democrats have been having, says Renée Cross, a political scientist at the University of Houston.

The discussion has been that Democrats “have to try something new,” she adds. “These two candidates, even though their styles are different, they have Democrats excited.”

Democratic confidence has been further boosted by an unlikely victory in a state senate runoff election in January, where a union president flipped a seat in a district that Mr. Trump had won by 17 points in 2024.

That has “made Democrats feel like, ‘This is really possible now,’” says Dr. Cross. “It really could be possible for Democrats to take a U.S. Senate seat.”

Kaylee Greenlee/Reuters

Kaylee Greenlee/Reuters

Racial tensions in primary

The primary contest has been marked by some racial tension. Earlier this month an influencer alleged that Representative Talarico had described former Representative Allred as a “mediocre Black man” to her. Mr. Allred broadcast the allegation in a social media video and announced his endorsement of Ms. Crockett. Mr. Talarico later said he had described Mr. Allred as a mediocre campaigner. Two liberal podcasters faced fan backlash – including accusations of racism – after discouraging donations to the Crockett campaign because they don’t think she could win the general election.

One of the early ads in the primary references the claim that Republicans helped nudge Ms. Crockett toward running because they believe she would be easier for the GOP to beat in a general election. That claim, along with discussions of her loud, fiery personality, play into common stereotypes of Black women, critics say.

Because both candidates are staunch progressives with few policy disagreements, these personality differences have been magnified, says Dr. Henson.

“In this race it’s more of an argument about temperament,” he adds. “And you can’t have that without thinking that race and gender are creeping into this race as well.”

Plenty of Democrats, he adds, think “people are using Jasmine Crocket’s combative style and rhetoric to cover concerns about how her race may affect her general election prospects.”

Jose Luis Gonzalez/Reuters

Jose Luis Gonzalez/Reuters

Coming down to the wire

Recent polls have returned different results. A Texas Politics Project poll released this week has Ms. Crockett leading by 12 points, and the overwhelming favorite among Black primary voters. A January poll conducted by Emerson College had Mr. Talarico with a nine-point lead. An internal poll from his campaign, released this week, had him with a four-point lead.

But notably the state lawmaker entered the primary with less name recognition, and that deficit appears to be narrowing. In August 2025, 54% of Texas voters responded “Don’t Know/No opinion” when asked for their view on him, according to the Texas Politics Project. That figure had dropped to 34% this month.

At the rally in Waco, several attendees said that they would support whichever Democrat wins the U.S. Senate primary in November – even if they favor Representative Talarico.

Dennis Hanley arrived at the rally having already voted. He said he’s been voting for Democrats in Texas for 30 years, throughout their long losing streak in statewide elections.

He has liked Mr. Talarico since his Joe Rogan podcast appearance, and he’s confident that the seminarian’s campaign means that Texas will finally elect a Democrat to statewide office.

“I’m also a Jasmine Crockett fan,” he said. “We need her. But I happen to follow [Talarico’s] ideology and his mindset more than hers.”

Deepen your worldview

with Monitor Highlights.

Already a subscriber? Log in to hide ads.

“The tide of the country is definitely turning,” he added. “People are sick of it, and I think that enough people are going to cross over – good and decent people from the other side – who’ve also had enough.”

Along with this story on the Democratic primary in Texas’ U.S. Senate race, we will run a separate story looking at the Republican primary in the same race in coming days.

Texas primary sizzles as two very different Democrats face off in Senate race

Democrats in Texas are getting excited.

Ahead of the March 3 U.S. Senate primary, more people have voted early in the Democratic race so far this year than voted in the entire 2022 primary, according to VoteHub, an independent and nonpartisan political analysis website.

The contest pits Rep. Jasmine Crockett, a member of Congress from Dallas, against state Rep. James Talarico, from the Austin suburbs. Voters have been casting their ballots in record numbers, giving the party faithful hope that one of their candidates has a chance of becoming the first Democrat elected statewide in Texas in over 30 years.

Why We Wrote This

In politically red Texas, Democrats rarely have hope. But their U.S. Senate primary race features two candidates whose contrasting styles and online reach are giving the party a jolt of energy.

In one sense, these numbers are not surprising. A midterm election typically favors the out-of-power party, and the in-power party tends to suffer even more if the president is unpopular. Both factors are true here for the Republican Party and President Donald Trump. Most polls show Mr. Trump’s favorability rating has dropped to averages in the low 40s nationally, and to about 50% among Texas voters.

But the Senate race is giving Democrats extra juice this year, experts and pollsters say. With the candidates’ policy positions mostly aligned, the Crockett-Talarico contest has become a clash of styles and strategies. It’s a race that Democrats will be closely watching nationwide, because of its importance to the party’s efforts to take control of the U.S. Senate and how it embodies divisions within the Democratic Party.

“Democrats could use a few high-profile dogfights in the primary because it gins up interest,” says James Henson, director of the Texas Politics Project at the University of Texas at Austin. “We don’t know if it will generate a victory for them, but so far it’s good to ... excite the base.”

Whoever wins the primary will face off in November’s general election against the winner of the Republican primary, where four-term Sen. John Cornyn faces a tough challenge from Texas Attorney General and MAGA firebrand Ken Paxton.

Jose Luis Gonzalez/Reuters

Jose Luis Gonzalez/Reuters

“Hunger for a different kind of politics”

On a chilly Monday evening in Waco, the line to see Representative Talarico stretched around the block. Whoever wins the Democratic primary is unlikely to win here – Mr. Trump won this mostly rural central Texas county by 33 points in 2024 – but Talarico supporters packed the ornate, century-old Hippodrome Theatre.

The turnout in the Republican stronghold encouraged Oliver Santander, who attended the rally with his sister, Emily.

“I’m just happy to see everyone here,” he said. “You don’t think your voice is as loud until you get around the crowd like this.”

Mr. Talarico entered the race as a relative unknown, but he has shot to stardom following a strategy popular among recent Democratic candidates. He has courted moderate Texans, touting his Christian faith and his work across the aisle as a state lawmaker.

He has also enjoyed several viral interviews. His first major national appearance came when he appeared on Joe Rogan’s podcast in July last year and Mr. Rogan said he should run for president. More recently, CBS pulled his interview with Stephen Colbert on the Late Show off the air over concerns it would violate a Federal Communications Commission regulation on political messaging. The interview instead appeared on the show’s YouTube channel, and the controversy only seemed to attract more eyeballs: at least 6 million more views than Colbert’s quarterly average on TV.

Henry Gass/The Christian Science Monitor

Henry Gass/The Christian Science Monitor

A Presbyterian seminary student, Mr. Talarico’s decision to make his faith – and his opposition to Christian Nationalism – a centerpiece of his politics has helped attract supporters. The hope among some of them lining up in the cold in Waco is that he can attract support from non-Democratic voters as well.

“I am tired of being pitted against my neighbor. I am tired of being told to hate my neighbor,” Mr. Talarico noted at his campaign event. “Across the political spectrum there is a deep hunger for a different kind of politics.”

Both Representatives Talarico and Crockett “have a lot to offer,” said Bill Purdue, a lifelong Democrat, as he waited to enter the theater.

But, he added, “a Democrat like Talarico, who comes from a strong religious point of view, would have a good opportunity to catch the ear of the many religious folks that live in Texas, particularly those that are perhaps sitting on the fence.”

Henry Gass/The Christian Science Monitor

Henry Gass/The Christian Science Monitor

“Try something new”

Mr. Talarico emphasized his calmer style and olive-branch strategy at the Waco event. “When you extend an open hand rather than a fist, you’ll be surprised how many people take that hand,” he said.

If he represents an open hand, Ms. Crockett has unashamedly branded herself as the fist in that analogy.

She entered the race in December with a national profile built through three years of aggressive, viral clashes with Republicans in Congress. Her firebrand style has enthused Democrats critical of the party’s unwillingness to take the fight to the Trump administration.

“We need someone who is a proven fighter in this moment, someone who will not back down, someone who will not fold,” she said in an interview last weekend. “My track record is clear. I have always fought for the people that I represented, and I’ve never folded.”

Ms. Crockett is not the style of candidate Democrats have chosen to run in recent top-ticket statewide races. Former U.S. Reps. Beto O’Rourke and Colin Allred – who ran for U.S. Senate in 2018 and 2024, respectively – campaigned as moderates, hoping to win over more centrist Republicans. Both lost.

While branding herself as a fighter, not a conciliator, Ms. Crockett is also running an unconventional campaign. She has spent little on campaign ads so far, and her rallies have often been pop-up events with little advance notice. She doesn’t appear to have a campaign manager or a media spokesperson. The Crockett campaign did not respond to multiple interview requests sent to a general campaign email.

These choices have frustrated national Democrats, NOTUS reported earlier this month, but her campaign says they are her best path to victory.

“We reject the DC playbook of politics as usual, because this moment — and winning — demands something different,” Karrol Rimal, a Crockett campaign staffer, told the news organization NOTUS in a statement.

This reflects a discussion national Democrats have been having, says Renée Cross, a political scientist at the University of Houston.

The discussion has been that Democrats “have to try something new,” she adds. “These two candidates, even though their styles are different, they have Democrats excited.”

Democratic confidence has been further boosted by an unlikely victory in a state senate runoff election in January, where a union president flipped a seat in a district that Mr. Trump had won by 17 points in 2024.

That has “made Democrats feel like, ‘This is really possible now,’” says Dr. Cross. “It really could be possible for Democrats to take a U.S. Senate seat.”

Kaylee Greenlee/Reuters

Kaylee Greenlee/Reuters

Racial tensions in primary

The primary contest has been marked by some racial tension. Earlier this month an influencer alleged that Representative Talarico had described former Representative Allred as a “mediocre Black man” to her. Mr. Allred broadcast the allegation in a social media video and announced his endorsement of Ms. Crockett. Mr. Talarico later said he had described Mr. Allred as a mediocre campaigner. Two liberal podcasters faced fan backlash – including accusations of racism – after discouraging donations to the Crockett campaign because they don’t think she could win the general election.

One of the early ads in the primary references the claim that Republicans helped nudge Ms. Crockett toward running because they believe she would be easier for the GOP to beat in a general election. That claim, along with discussions of her loud, fiery personality, play into common stereotypes of Black women, critics say.

Because both candidates are staunch progressives with few policy disagreements, these personality differences have been magnified, says Dr. Henson.

“In this race it’s more of an argument about temperament,” he adds. “And you can’t have that without thinking that race and gender are creeping into this race as well.”

Plenty of Democrats, he adds, think “people are using Jasmine Crocket’s combative style and rhetoric to cover concerns about how her race may affect her general election prospects.”

Jose Luis Gonzalez/Reuters

Jose Luis Gonzalez/Reuters

Coming down to the wire

Recent polls have returned different results. A Texas Politics Project poll released this week has Ms. Crockett leading by 12 points, and the overwhelming favorite among Black primary voters. A January poll conducted by Emerson College had Mr. Talarico with a nine-point lead. An internal poll from his campaign, released this week, had him with a four-point lead.

But notably the state lawmaker entered the primary with less name recognition, and that deficit appears to be narrowing. In August 2025, 54% of Texas voters responded “Don’t Know/No opinion” when asked for their view on him, according to the Texas Politics Project. That figure had dropped to 34% this month.

At the rally in Waco, several attendees said that they would support whichever Democrat wins the U.S. Senate primary in November – even if they favor Representative Talarico.

Dennis Hanley arrived at the rally having already voted. He said he’s been voting for Democrats in Texas for 30 years, throughout their long losing streak in statewide elections.

He has liked Mr. Talarico since his Joe Rogan podcast appearance, and he’s confident that the seminarian’s campaign means that Texas will finally elect a Democrat to statewide office.

“I’m also a Jasmine Crockett fan,” he said. “We need her. But I happen to follow [Talarico’s] ideology and his mindset more than hers.”

Deepen your worldview

with Monitor Highlights.

Already a subscriber? Log in to hide ads.

“The tide of the country is definitely turning,” he added. “People are sick of it, and I think that enough people are going to cross over – good and decent people from the other side – who’ve also had enough.”

Along with this story on the Democratic primary in Texas’ U.S. Senate race, we will run a separate story looking at the Republican primary in the same race in coming days.

Wealthy universities, facing steep endowment tax hikes, cut PhDs and libraries

Princeton University President Christopher Eisgruber lobbied members of Congress repeatedly to deter an increase in the endowment tax on colleges and universities. Instead, when the One Big Beautiful Bill Act passed last summer, Princeton became one of a handful of schools whose endowment tax ballooned.

Now, President Eisgruber is preparing his institution for change as it prepares to pay an endowment tax of 8% on net investment earnings next year, up from 1.4%. He’s asked department heads to make budget cuts and says more could come. He announced this month that over the next decade, Princeton expects to lose $11 billion in endowment investment earnings.

“Princeton will continue to evolve, but in the future it will more often have to do so through efficiency and substitution rather than addition,” Mr. Eisgruber wrote to the Princeton community on Feb. 2, in his “State of the University” letter.

Why We Wrote This

Some prominent U.S. universities are paring back campus spending in response to endowment tax hikes passed by Congress and the Trump administration’s drive to reform higher education.

Schools that are expected to pay the new top-bracket endowment tax rate include elite universities with billion-dollar endowments, such as Harvard, Princeton, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Stanford, and Yale. Leaders at those schools and other institutions facing smaller, but significant, tax hikes are taking steps now to prepare for the tax hit ahead. Actions include cutting spots in doctoral programs and scaling back campus libraries.

Universities are making these adjustments as the Trump administration continues its sweeping efforts – through lawsuits and the withholding of federal research funding – to reshape university cultures to be, as government officials describe it, more receptive to conservative viewpoints and more oriented toward career training.

Seth Wenig/AP/File

Seth Wenig/AP/File

Lynn Cooley, dean of Yale University’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, says that her school is cutting doctoral programs across the board by lowering admissions targets in response to the coming tax.

She worries that “fewer discoveries will emerge” as a result, and “fewer curious, creative, motivated young people will have access to the education needed to carry out rigorous research that benefits lives across the region, country, and globe,” Dr. Cooley wrote in an email to the Monitor.

Alternatively, Mark Schneider, a senior fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, believes the endowment tax will force universities to adapt to market realities. He says the United States is overproducing doctoral students in obscure fields and that Congress could instead allocate endowment tax revenue to workforce programs at regional universities.

“Billions of dollars go into [college and university] endowments, and now that they’re going to be taxed, shouldn’t the Congress decide where that money should go?” Mr. Schneider says. “Should it go to Harvard? Or should it go to a regional campus where we’re training people for jobs in the future?”

“Only a very small part of the American population are in these [elite] schools,” he adds. “Most students go to schools within 50 miles of their house.”

How the endowment tax is changing

Congress initially set the endowment tax on private colleges’ and universities’ investment earnings at 1.4% in 2017 during President Donald Trump’s first term. Last July, Congress included significant hikes in that rate in its tax-and-spending bill, which the White House championed. The new structure includes rates of 1.4%, 4%, and 8%, depending on each school’s endowment size and student population.

The new tax law applies to private, nonprofit colleges and universities with minimum endowments of $500,000 to $750,000 per student. Schools with endowments of $750,000 to $2 million per student will pay a 4% tax, and those with endowments of more than $2 million per student will pay 8%.

Colleges and universities with a total enrollment of 3,000 or fewer students are exempt from the new tax rates, which go into effect this year.

The American Enterprise Institute estimates that about 20 universities will be subject to the endowment tax in the first year. Harvard, Princeton, MIT, Stanford, and Yale, all of which have endowments worth tens of billions of dollars, will be taxed at the highest rate. Harvard, which leads with a $53 billion endowment, will have the highest bill at $368.2 million, followed by Yale with $280 million and Princeton at more than $217 million, according to AEI estimates.

The money will flow into the U.S. Treasury’s general account, which acts like the U.S. government’s checking account. Funds there are managed by the Treasury Department, with expenditures allocated by Congress.

What actions are universities taking now?

After news of the new tax rate hit, Stanford University announced that it would lay off 363 people. Other schools have taken similar measures.

Dr. Cooley at Yale says the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences now has a smaller budget as a result of the new endowment tax. University officials estimate their new endowment tax bill will exceed the annual budgets of eight of Yale’s 15 schools combined.

As a result, hits to Yale’s graduate programs will include a 13% reduction in Ph.D. students over the next three years. Enrollment in science and engineering doctoral programs will decrease by 5%, a smaller drop because those departments receive more research and foundation funding and are less reliant on the university’s endowment.

MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is also feeling the crunch from the higher tax rate. At the end of the fall semester in 2025, President Sally Kornbluth and other administrators sent a note to the school community outlining an expected $300 million annual cost to the university from the endowment tax and federal research funding cuts.

Her note referenced changes to the institution’s library system, including layoffs, the closure of two service desks, and a shift to digital-first material. MIT will also end leases for office space and freeze merit raises for employees earning more than $85,000, except in the case of promotions. Dr. Kornbluth said that MIT is looking for ways to increase revenue through avenues like fundraising and in-person and online offerings.

“Taken together, the framework we’ve outlined will allow MIT to navigate these rough financial waters while maintaining its famous momentum,” the letter read. “But – as the last year has demonstrated – the policy weather could certainly grow worse. We are preparing scenarios for that too.”

On the tax bubble

Some schools, like Colgate University, sit on the edge of the endowment tax threshold. The liberal arts school in central New York has a student enrollment of about 3,000 to 3,200. As of February, its endowment stands at $1.44 billion. That puts the university close to the 1.4% bracket.

“There are no reasonable nor responsible measures to avoid the tax,” says Joseph Hope, Colgate’s senior vice president of finance and chief investment officer, via email. “When we eventually join the group of schools subject to this tax, it will be because we have achieved a period of robust growth that directly enhances our ability to support our academic mission.”

Mr. Hope says that Colgate administrators have not yet discussed lowering enrollment below 3,000 students to avoid having to pay the tax.

“Our priority is delivering a world-class residential liberal arts education,” he says, “rather than letting tax thresholds dictate what we do.”

Why would Trump strike Iran? How lack of clarity imperils a diplomatic deal.

Will he or won’t he?

For weeks, Washington, Middle East capitals, and indeed many points beyond have been gripped with speculation over whether President Donald Trump would attack Iran – a move many analysts and some advisers in Mr. Trump’s inner circle have warned could spark a broader war.

At the same time, another question has remained largely unanswered concerning the president’s potential recourse to a military intervention against the Islamic Republic: Why would he?

Why We Wrote This

President Donald Trump’s brief mention of Iran in his State of the Union address was still short of a complete argument for how and why striking Iran, which would risk a wider Middle East conflict, would further U.S. interests.

Now, as indirect talks between the United States and Iran are set to resume in Geneva on Thursday, against the backdrop of the largest U.S. armada assembled in the Middle East since the Iraq War, the answer to the “why” question remains incomplete at best.

Mr. Trump’s recent comments on Iran and those of some of his advisers have suggested four different objectives that could be motivating U.S. policy, numerous U.S.-Iran analysts say. Chief among them is Iran’s nuclear program and eliminating any possibility of Iran acquiring a nuclear weapon.

Other objectives the president is considering, comments suggest, are taking out Iran’s ballistic missile arsenal and production capabilities; riding to the rescue of Iran’s anti-regime protesters, as Mr. Trump pledged in January; weakening Iran’s support for its regional proxies; and, lastly, some form of regime change.

The president dedicated only a few lines of his State of the Union address Tuesday to Iran, but he did touch on some of these potential goals underpinning his next steps.

Majid Asgaripour/West Asia News Agency

Majid Asgaripour/West Asia News Agency

“My preference is to solve this problem through diplomacy,” Mr. Trump said, “but I will never allow the world’s number one sponsor of terrorism to have a nuclear weapon. Can’t let that happen.”

Referring to what he’s looking for in the ongoing negotiations, he said, “We haven’t heard the secret words: ‘We [Iran] will never have a nuclear weapon.’”

Touching on other factors that could be driving administration deliberations, the president cited his disdain for a regime “that has killed at least 32,000 protesters,” as well as a missile stockpile “that can threaten Europe and our bases overseas.” (Rights groups monitoring the recent Iranian unrest say the number of dead confirmed so far is at least 7,000, which would still make the crackdown the regime’s deadliest.)

Emboldened, yet hesitating

For many critics and analysts, that hardly explains why the United States would risk a broader and unpredictable war in the Middle East.

In the absence of a clear case for how striking Iran would further U.S. interests, some analysts say the president appears to be emboldened to take military action by what he has characterized as recent successes. First, the airstrikes last June against Iranian nuclear facilities, and then the January special-forces operation that seized Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro.

“Trump’s the guy in the casino who’s on a roll. He’s just won a bunch of money at the Venezuela craps table, and he hasn’t forgotten his Iran winnings from June,” says Rosemary Kelanic, an expert in energy security and U.S. grand strategy at Defense Priorities, a Washington think tank advocating restraint in U.S. foreign policy.

“Now he’s at the table again,” she adds, “with a lot of chips and some congressional hawks and [Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin] Netanyahu whispering in his ear that Iran is weak so it’s his opportunity to go big.”

She says the lack of clarity on just what President Trump’s objectives are can make getting the deal he says he prefers more difficult. “If the Iranians are unclear if Trump really wants a deal, but suspect he might be bent on regime change, then there’s no incentive for Iran to go for concessions,” she says.

Others say the president appears to be leaning toward a limited military strike that is beyond a token signal but short of full regime change. Nuclear sites would be targeted again, but this time missile infrastructure and government power centers as well, to convince the Iranians to get serious about negotiations. Mr. Trump confirmed last week he is indeed considering such an option.

Stelios Misinas/Reuters

Stelios Misinas/Reuters

“What President Trump has on the table seems to be a ‘decapitation strike’ that would be designed to target a range of significant military infrastructure and Iran’s leadership so that the U.S. can start negotiating seriously in a new reality and with a new successor leadership,” says Arash Reisinezhad, a visiting assistant professor at Tufts University’s Fletcher School in Medford, Mass.

“So what I see is a strategy of three steps,” he says, adding, “The negotiations that are taking place, then the decapitation strikes, and then a return to serious negotiations” with a successor set of Iranian powers.

“Iran gets a vote”

Such an approach might be “more realistic than complete regime change,” Dr. Reisinezhad says, “but it would still be very risky – which explains why Mr. Trump is hesitating.”

He says Iran could be expected to immediately strike back at U.S. interests in the region, including military bases, energy installations, and Israel.

Others agree the “strike to negotiate” option is fraught with danger.

“The theory that a round of targeted strikes can lead to concessions from Iran is completely wrong,” says Dr. Kelanic. “Iran gets a vote in this, and they’ve signaled every way they can that they are going to respond hard to any attacks. If Trump opts for any attack,” she adds, “any deal is going to be off the table.”

Some analysts suspect that Mr. Trump’s overriding motivation is his assurances to the American public as far back as his 2016 presidential campaign that he could deliver a much better deal with Iran than President Obama’s 2015 nuclear deal – which he withdrew from in 2018. Going to war with Iran instead would sully his self-image as a greater dealmaker than any previous president, they say.

Deepen your worldview

with Monitor Highlights.

Already a subscriber? Log in to hide ads.

For Dr. Reisinezhad, an unpredictable military engagement with Iran also risks seriously undermining the administration’s broader national security interests, as laid out in last month’s National Security Strategy.

“The U.S. under this administration has just said it’s most important focus should be Taiwan and the South China Sea, as well as the Western Hemisphere,” he says. “If the U.S. gets stuck in the Middle East and has to turn away from Asia,” he adds, “that’s going to be good for China, and for Russia.”

Satellite data centers might help Earth. But what about space?

A new space race is underway. But this one is not so much between nations as it is between tech companies.

The quest? Be the first to launch data centers into space.

The stakes? According to some astronomers, the night sky itself.

Why We Wrote This

While space-based data centers promise to alleviate Earth’s energy crisis, the next frontier of innovation hinges on designing orbital infrastructure that is sustainable and avoids creating a “dumping ground” in orbit.

This month, Elon Musk announced that his space-faring company, SpaceX, had merged with his artificial intelligence company, xAI, in an effort to launch 1 million satellites that could work together to form extraterrestrial data centers. Google’s Project Suncatcher proposed creating data centers in space by using lasers to transmit data between satellites in near proximity to one another. And late last year, a competitor named Starcloud launched a refrigerator-sized satellite into space – the first step toward its own orbiting data center.

None of this will be technologically easy. But tech companies claim that data centers in space could become more cost-efficient than the massive warehouses of computer servers devouring land, water, and electricity on Earth.

“Global electricity demand for AI simply cannot be met with terrestrial solutions, even in the near term, without imposing hardship on communities and the environment,” Mr. Musk said in a statement after announcing his merger. “By directly harnessing near-constant solar power with little operating or maintenance costs, these satellites will transform our ability to scale compute. It’s always sunny in space!”

Ted Shaffrey/AP/File

Ted Shaffrey/AP/File

However, some astronomers and economists are concerned that what might be beneficial to one environment might be harmful to another. There are already about 14,000 satellites in space. Sometimes, they collide. They also spawn space junk – everything from spent rocket boosters to loose bolts. On Jan. 30, for instance, one of Russia’s old spy satellites disintegrated into bits and pieces.

Putting sizable data centers into orbit could compound those challenges. In recent decades, there’s been a growing awareness that mankind could be repeating the mistake it made with the oceans, viewing space as an inexhaustible resource where we can dump things. Out of sight, out of mind. This has prompted scientists, economists, and politicians to focus on solutions that facilitate technological progress yet also reduce pollution of the orbital commons.

“Increasingly, people in this realm ... are beginning to recognize that space is an environment, much as the Earth is an environment,” says Akhil Rao, a former NASA economist.

Still, in 2024, data centers in the United States accounted for 4.4% of the nation’s electricity consumption. A study last year from the Environmental and Energy Study Institute found that large data centers can consume 5 million gallons of water a day.

The trade-off on the other side of the environmental ledger is often less obvious. In 1978, astrophysicist Don Kessler co-wrote an influential paper about the potential consequences of an accumulation of satellites around the planet. Even without data centers in orbit, it’s getting cluttered up there.

Astronomers are particularly concerned about “the Kessler Effect.” That’s when orbital collisions create space junk, which begets even more collisions and even more debris. In 2009, for instance, a communications satellite slammed into a disused Russian military spacecraft. Each object was reduced to clouds of shrapnel that continued traveling around the planet. It takes about 11 years for gravity to bring smaller objects in lower orbits down to Earth.

There are currently 25,000 tracked pieces of debris in orbit, according to Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist who recently retired from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. And that’s just the stuff we can see. Smaller objects, such as frozen globules of propellant expelled by satellites, whiz through orbit faster than bullets, becoming hazards for astronauts during spacewalks. In December, a spacecraft docked at China’s space station was rendered temporarily inoperable because of a damaged window after a suspected space-debris strike.

Unless there’s a cleanup, space might eventually become too hazardous to safely traverse. Time to call in the space garbage trucks.

A British and Japanese company called Astroscale is set to launch a debris-removal vehicle this year. It will shepherd disused satellites and rocket boosters into a lower orbit so that they’ll burn up reentering the atmosphere. Other cleanup technologies are being tested. In 2018, a European RemoveDebris satellite successfully captured an object in space with a polyethylene net. A Swiss company named ClearSpace is developing a vehicle with claw-like robot arms to latch onto satellites that need to be scrapped.

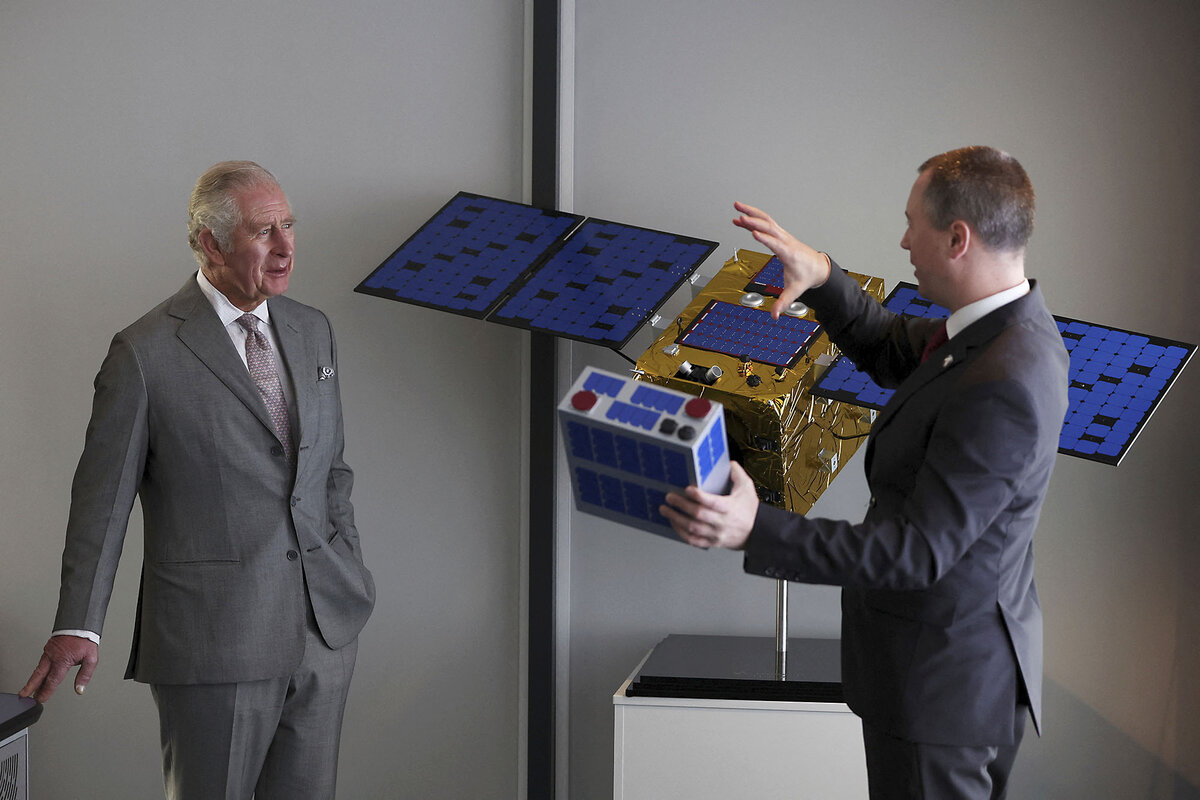

Paul Childs/PA/AP/FIle

Paul Childs/PA/AP/FIle

“China, which hasn’t in the past had such a great record on space debris, is actually the first country to have done a real debris-

removal action,” says Dr. McDowell. “In this case, in geostationary orbit, 36,000 kilometers up, where they sent a tug up to a dead navigation satellite of theirs and towed it to a higher – what’s called a graveyard – orbit and released it there.”

There’s a common interest in solving the tragedy of the space commons, says Dr. McDowell. An organization named the

Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee provides recommendations about best practices. But these aren’t binding. In violation of the guidelines, Russia conducted a military test to blow up one of its satellites five years ago.

Many commercial companies, such as Starlink, have followed good disposal practices, says Dr. Rao, the former NASA economist. And they have an incentive to do so. If companies leave dead satellites in space, then they are creating risks for their own active satellites.

Still, compliance can be tricky. Satellites become less responsive to commands over time. By the time that satellites pass their expiration date, they’re no longer able to de-orbit.

Economists have been proposing incentive-based solutions. For example, regulatory agencies in various nations could charge companies a tax for as long as their satellite is in space. Agencies could issue a bond whenever a satellite is launched. The bond is only redeemable upon de-orbit. Money raised by the bond could be put toward space cleanup activities.

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

Melanie Stetson Freeman/Staff

Among those clamoring for change are astronomers. Satellites create light pollution in the night sky, says John Barentine, former director of public policy for the International Dark Sky Association in Tucson, Arizona.

The man-made celestial objects, whose solar-paneled wings make them look like metallic dragonflies, reflect sunlight back down to the ground. They show up in astronomical images. Astronomers on the lookout for dangerous asteroids – such as the one that crashed in Russia in 2013 with a shock wave that injured 1,500 people and damaged buildings – say that the glint of satellites at dawn and dusk also makes it harder to spot things behind them. Data center satellites would be even bigger and brighter than regular ones.

“Thousands of bright satellites would actually degrade our ability to detect some of the threatening [near Earth objects],” explains Olivier Hainaut, an astronomer at the European Southern Observatory in Chile, via email.

Deepen your worldview

with Monitor Highlights.

Already a subscriber? Log in to hide ads.

Today, the average person isn’t thinking a whole lot about space debris. That broader shift in thought will come, Dr. Barentine says, once the public understands how it affects them. That’s what motivated him to co-found the Center for Space Environmentalism last year. His goal is to bring extraterrestrial issues to public attention. That often starts with telescopes in backyards.

“Cultivating a closer relationship between humans and the cosmos through the medium of the night sky could be a way to increase appreciation for the space environment and its inextricable connection to our own environment,” Dr. Barentine says.

3 in 5 US undergrads struggle with basic needs. How some colleges are helping.

The food pantry at Austin Community College’s Highland campus was busy, with a steady stream of students stocking up on essentials. Many items had posted limits – one cabbage, two onions, three potatoes – but zucchini were in abundance. “Take more,” the cashier urged the shoppers, some stopping in between classes.

And they did.

With 3 in 5 American undergraduates reporting food or housing insecurity, a new model of support has taken hold on college campuses. From Harvard University to Hostos Community College in New York City to the University of Minnesota, schools are offering food pantries, emergency grants, and transportation help. It is a matter of survival - for both students and colleges.

Why We Wrote This

Students without basic resources often drop out. Schools that support undergraduates’ basic needs are reporting better retention and narrower achievement gaps.

It’s also a significant expansion of colleges’ traditional role.

“Some people look at these efforts and wonder, ‘Why would a college provide this?’” said Marisa Vernon-White, vice president of enrollment management and student services at Lorain County Community College in Elyria, Ohio. “They ask, ‘Isn’t your job education and workforce training?’”

But Ms. Vernon-White and others say it’s in colleges’ best interest to see their roles more broadly. Students who lack resources – who have to skip meals or hunt for a safe place to sleep – often drop out, costing colleges millions in unrealized revenue at a time of declining enrollment and shrinking public funding.

Colleges that have committed to addressing students’ basic needs report improvements in retention and a narrowing of achievement gaps.

In the six years since Lorain Community College opened an Advocacy and Resource Center, the share of students graduating on time has risen 15 percentage points, to roughly 40%.

How we got here

A college education has traditionally provided a golden ticket to the middle class, a stepping stone to higher pay, better job prospects, and a more secure future. But its price tag keeps rising. And student aid isn’t keeping pace. Fifty years ago, the federal Pell Grant covered three-quarters of the cost of attending a four-year public college. Today, it covers less than a quarter.

The result: a growing number of students struggle to afford food or stable housing, especially in the nation’s community colleges, which serve 40% of all undergraduates. About 14% of students report experiencing homelessness, according to a survey by The Hope Center for Student Basic Needs at Temple University in Philadelphia.

Such statistics have spurred colleges of all types – including elite schools trying to help break cycles of generational poverty – to create a range of basic support services. Some even help students apply for food stamps and other public benefits. It’s partly about the math. But it’s also about building community.

An early leader in the culture of care

Few college leaders have tackled student poverty as systemically as Russell Lowery-Hart, chancellor of Austin Community College, a large public college district with 11 locations across central Texas.

Before coming to Austin in 2023, Dr. Lowery-Hart served as president of Amarillo College, a community college in the Texas Panhandle. There, he built a “Culture of Caring” that has been studied by researchers, replicated by colleges, and credited with raising Amarillo’s graduation rate by 13 percentage points during his tenure.

“Our students are an $88 emergency away from dropping out,’’ Dr. Lowery-Hart said on Community College Podcast. “We have to help our students with their basic need barriers if we are going to help them with their learning and their degree completion.’’

Now, as Dr. Lowery-Hart takes his model to Austin Community College, a district with more than four times as many students as Amarillo, the movement he launched a decade ago feels more established and yet more vulnerable than ever.

These days, most colleges – public, private, two-year, and four-year alike – provide students with some basic needs support. Some – mostly wealthier four-year programs – also offer scholarships that help cover room and board.

In Congress and state legislatures, lawmakers from both political parties are raising alarms about student hunger and homelessness, and introducing legislation to expand basic needs support.

Austin CC District

Austin CC District

Yet many of the basic services colleges offer – running on an average budget of just $12,000 – are understaffed and underfunded. And resources are likely to become even scarcer in the coming years, as state legislatures, forced to shoulder more of the costs of public benefits programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, known as “SNAP,’’, and Medicaid, scale back spending in other areas.

A vision of care

When Dr. Lowery-Hart first introduced his vision of love-centered leadership to Amarillo’s general assembly in 2015, many faculty were skeptical, he recalls.

Some saw the vision as “unserious” – a threat to academic rigor.

Other faculty members said they resented Dr. Lowery-Hart’s decision to invest in students after faculty and staff layoffs. In one survey, a professor wrote that the college was “killing faculty positions to pay for the president’s ‘poor children’ schemes.”

“They said, ‘You’re asking us to love students, and no one is loving us,’” Dr. Lowery-Hart recalled.

Back then, most college leaders were still in the dark about the scope and impact of homelessness and hunger on their campuses, said Katharine Broton, a researcher and professor studying basic needs insecurity at The University of Iowa. Some college presidents would even insist they didn’t have hungry and homeless students.

“I had people say flat out, ‘I don’t believe it. I think students are lying,” Ms. Broton says.

In 2015, she and her colleagues at The Wisconsin HOPE Lab, a predecessor to The Hope Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, published their first survey of basic needs insecurity among community college students. It helped awaken college leaders to the struggles many students were facing.

A decade later, most readily acknowledge that hunger and homelessness are big issues that affect student retention.

But not everyone is convinced that cash-strapped colleges should be responsible for solutions. Skeptics argue that colleges aren’t set up to serve as social service agencies and caution about the costs of “mission creep.”

Pinning improvements in student outcomes on food and housing support programs is tricky; some of the growth seen at colleges like Lorain and Amarillo might be due to other factors. It’s also possible that students who seek help are more motivated or resilient than those who don’t, and thus more likely to persist in college, regardless of the support they receive.

Though some studies have found links between specific interventions and improvements in grades or retention, rigorous research on this topic is rare.

“There’s not a ton of hard evidence on which strategies are most impactful,” said David Thompson, a practitioner-researcher at The Hope Center.

Still, both Ms. Vernon-White and Dr. Lowery-Hart believe that basic needs programs have helped reduce college dropout rates at their schools.