Sixteen Claude AI agents working together created a new C compiler

Sixteen Claude AI agents working together created a new C compiler

The $20,000 experiment compiled a Linux kernel but needed deep human management.

Credit:

akinbostanci via Getty Images

Credit:

akinbostanci via Getty Images

Story text

Size

Small

Standard

Large

Width

*

Standard

Wide

Links

Standard

Orange

* Subscribers only

Credit:

akinbostanci via Getty Images

Credit:

akinbostanci via Getty Images

Story text

Size

Small

Standard

Large

Width

*

Standard

Wide

Links

Standard

Orange

* Subscribers onlyLearn more

Amid a push toward AI agents, with both Anthropic and OpenAI shipping multi-agent tools this week, Anthropic is more than ready to show off some of its more daring AI coding experiments. But as usual with claims of AI-related achievement, you’ll find some key caveats ahead.

On Thursday, Anthropic researcher Nicholas Carlini published a blog post describing how he set 16 instances of the company’s Claude Opus 4.6 AI model loose on a shared codebase with minimal supervision, tasking them with building a C compiler from scratch.

Over two weeks and nearly 2,000 Claude Code sessions costing about $20,000 in API fees, the AI model agents reportedly produced a 100,000-line Rust-based compiler capable of building a bootable Linux 6.9 kernel on x86, ARM, and RISC-V architectures.

Carlini, a research scientist on Anthropic’s Safeguards team who previously spent seven years at Google Brain and DeepMind, used a new feature launched with Claude Opus 4.6 called “agent teams.” In practice, each Claude instance ran inside its own Docker container, cloning a shared Git repository, claiming tasks by writing lock files, then pushing completed code back upstream. No orchestration agent directed traffic. Each instance independently identified whatever problem seemed most obvious to work on next and started solving it. When merge conflicts arose, the AI model instances resolved them on their own.

The resulting compiler, which Anthropic has released on GitHub, can compile a range of major open source projects, including PostgreSQL, SQLite, Redis, FFmpeg, and QEMU. It achieved a 99 percent pass rate on the GCC torture test suite and, in what Carlini called “the developer’s ultimate litmus test,” compiled and ran Doom.

It’s worth noting that a C compiler is a near-ideal task for semi-autonomous AI model coding: The specification is decades old and well-defined, comprehensive test suites already exist, and there’s a known-good reference compiler to check against. Most real-world software projects have none of these advantages. The hard part of most development isn’t writing code that passes tests; it’s figuring out what the tests should be in the first place.

The compiler also has clear limitations that Carlini was upfront about. It lacks a 16-bit x86 backend needed to boot Linux from real mode, so it calls out to GCC for that step. Its own assembler and linker remain buggy. Even with all optimizations enabled, it produces less efficient code than GCC running with all optimizations disabled. And the Rust code quality, while functional, does not approach what an expert Rust programmer would produce. “The resulting compiler has nearly reached the limits of Opus’s abilities,” Carlini wrote. “I tried (hard!) to fix several of the above limitations but wasn’t fully successful. New features and bugfixes frequently broke existing functionality.”

Those limitations may actually be more informative than the successes. Carlini reports that toward the end of the project, fixing bugs and adding features “frequently broke existing functionality,” a pattern familiar to anyone who has watched a codebase grow beyond the point where any contributor fully understands it.

And that limitation is even more common when dealing with AI coding agents, which lose coherence over time. The model hit this wall at around 100,000 lines, which suggests a practical ceiling for autonomous agentic coding, at least with current models.

The human work behind the automation

Anthropic describes the compiler as a “clean-room implementation” because the agents had no Internet access during development. But that framing is somewhat misleading. The underlying model was trained on enormous quantities of publicly available source code, almost certainly including GCC, Clang, and numerous smaller C compilers. In traditional software development, “clean room” specifically means the implementers have never seen the original code. By that standard, this isn’t one.

On Hacker News, the distinction drew sharp debate, reflective of a controversial reception to the news among developers. “It was rather a brute force attempt to decompress fuzzily stored knowledge contained within the network,” wrote one commenter.

The $20,000 figure also deserves some context. That number covers only API token costs and excludes the billions spent training the model, the human labor Carlini invested in building the scaffolding, and the decades of work by compiler engineers who created the test suites and reference implementations that made the project possible.

And that scaffolding was not trivial, which makes any claim of “autonomous” work on the C compiler among the AI agents dubious. While the headline result is a compiler written without human pair-programming, much of the real work that made the project function involved designing the environment around the AI model agents rather than writing compiler code directly. Carlini spent considerable effort building test harnesses, continuous integration pipelines, and feedback systems tuned for the specific ways language models fail.

He found, for example, that verbose test output polluted the model’s context window, causing it to lose track of what it was doing. To address this, Carlini designed test runners that printed only a few summary lines and logged details to separate files.

He also found that Claude has no sense of time and will spend hours running tests without making progress, so he built a fast mode that samples only 1 percent to 10 percent of test cases. When all 16 agents got stuck trying to fix the same Linux kernel bug simultaneously, he used GCC as a reference oracle, randomly compiling most kernel files with GCC and only a subset with Claude’s compiler, so each agent could work on different bugs in different files.

“Claude will work autonomously to solve whatever problem I give it,” Carlini wrote. “So it’s important that the task verifier is nearly perfect, otherwise Claude will solve the wrong problem.”

None of this should obscure what the project actually demonstrates. A year ago, no language model could have produced anything close to a functional multi-architecture compiler, even with this kind of babysitting and an unlimited budget. The methodology of parallel agents coordinating through Git with minimal human supervision is novel, and the engineering tricks Carlini developed to keep the agents productive (context-aware test output, time-boxing, the GCC oracle for parallelization) could potentially represent useful contributions to the wider use of agentic software development tools.

Carlini himself acknowledged feeling conflicted about his own results. “Building this compiler has been some of the most fun I’ve had recently, but I did not expect this to be anywhere near possible so early in 2026,” he wrote. He also raised concerns rooted in his previous career in penetration testing, noting that “the thought of programmers deploying software they’ve never personally verified is a real concern.”

Benj Edwards

Senior AI Reporter

Benj Edwards

Senior AI Reporter

Benj Edwards

Senior AI Reporter

Benj Edwards

Senior AI Reporter

Malicious packages for dYdX cryptocurrency exchange empties user wallets

Malicious packages for dYdX cryptocurrency exchange empties user wallets

Incident is at least the third time the exchange has been targeted by thieves.

Credit:

Getty Images

Credit:

Getty Images

Story text

Size

Small

Standard

Large

Width

*

Standard

Wide

Links

Standard

Orange

* Subscribers only

Credit:

Getty Images

Credit:

Getty Images

Story text

Size

Small

Standard

Large

Width

*

Standard

Wide

Links

Standard

Orange

* Subscribers onlyLearn more

Open source packages published on the npm and PyPI repositories were laced with code that stole wallet credentials from dYdX developers and backend systems and, in some cases, backdoored devices, researchers said.

“Every application using the compromised npm versions is at risk ….” the researchers, from security firm Socket, said Friday. “Direct impact includes complete wallet compromise and irreversible cryptocurrency theft. The attack scope includes all applications depending on the compromised versions and both developers testing with real credentials and production end-users.”

Packages that were infected were:

- 3.4.1

- 1.22.1

- 1.15.2

- 1.0.31

PyPI (dydx-v4-client):

- 1.1.5post1

Perpetual trading, perpetual targeting

dYdX is a decentralized derivatives exchange that supports hundreds of markets for “perpetual trading,” or the use of cryptocurrency to bet that the value of a derivative future will rise or fall. Socket said dYdX has processed over $1.5 trillion in trading volume over its lifetime, with an average trading volume of $200 million to $540 million and roughly $175 million in open interest. The exchange provides code libraries that allow third-party apps for trading bots, automated strategies, or backend services, all of which handle mnemonics or private keys for signing.

The npm malware embedded a malicious function in the legitimate package. When a seed phrase that underpins wallet security was processed, the function exfiltrated it, along with a fingerprint of the device running the app. The fingerprint allowed the threat actor to correlate stolen credentials to track victims across multiple compromises. The domain receiving the seed was dydx[.]priceoracle[.]site, which mimics the legitimate dYdX service at dydx[.]xyz through typosquatting.

The malicious code available on PyPI contained the same credential theft function, although it also implemented a remote access Trojan (RAT) that allowed the execution of new malware on infected systems. The backdoor received commands from dydx[.]priceoracle[.]site. The domain was registered on January 9, 17 days before the malicious package was uploaded to PyPI.

The RAT, Socket said:

- Runs as a background daemon thread

- Beacons to the C2 server every 10 seconds

- Receives Python code from the server

- Executes it in an isolated subprocess with no visible output

- Uses a hardcoded authorization token:

490CD9DAD3FAE1F59521C27A96B32F5D677DD41BF1F706A0BF85E69CA6EBFE75

Once installed, the threat actors could:

- Execute arbitrary Python code with user privileges

- Steal SSH keys, API credentials, and source code

- Install persistent backdoors

- Exfiltrate sensitive files

- Monitor user activity

- Modify critical files

- Pivot to other systems on the network

Socket said the packages were published to npm and PyPI by official dYdX accounts, an indication that they were compromised and used by the attackers. dYdX officials didn’t respond to an email seeking confirmation and additional details.

The incident is at least the third time dYdX has been targeted in attacks. Previous events include a September 2022 uploading of malicious code to the npm repository and the commandeering in 2024 of the dYdX v3 website through DNS hijacking. Users were redirected to a malicious site that prompted them to sign transactions designed to drain their wallets.

“Viewed alongside the 2022 npm supply chain compromise and the 2024 DNS hijacking incident, this [latest] attack highlights a persistent pattern of adversaries targeting dYdX-related assets through trusted distribution channels,” Socket said. “The threat actor simultaneously compromised packages in both npm and PyPI ecosystems, expanding the attack surface to reach JavaScript and Python developers working with dYdX.”

Anyone using the platform should carefully examine all apps for dependencies on the malicious packages listed above.

Dan Goodin

Senior Security Editor

Dan Goodin

Senior Security Editor

Dan Goodin

Senior Security Editor

Dan Goodin

Senior Security Editor

AI companies want you to stop chatting with bots and start managing them

AI companies want you to stop chatting with bots and start managing them

Claude Opus 4.6 and OpenAI Frontier pitch a future of supervising AI agents.

Credit:

demaerre via Getty Images

Credit:

demaerre via Getty Images

Story text

Size

Small

Standard

Large

Width

*

Standard

Wide

Links

Standard

Orange

* Subscribers only

Credit:

demaerre via Getty Images

Credit:

demaerre via Getty Images

Story text

Size

Small

Standard

Large

Width

*

Standard

Wide

Links

Standard

Orange

* Subscribers onlyLearn more

On Thursday, Anthropic and OpenAI shipped products built around the same idea: instead of chatting with a single AI assistant, users should be managing teams of AI agents that divide up work and run in parallel. The simultaneous releases are part of a gradual shift across the industry, from AI as a conversation partner to AI as a delegated workforce, and they arrive during a week when that very concept reportedly helped wipe $285 billion off software stocks.

Whether that supervisory model works in practice remains an open question. Current AI agents still require heavy human intervention to catch errors, and no independent evaluation has confirmed that these multi-agent tools reliably outperform a single developer working alone.

Even so, the companies are going all-in on agents. Anthropic’s contribution is Claude Opus 4.6, a new version of its most capable AI model, paired with a feature called “agent teams” in Claude Code. Agent teams let developers spin up multiple AI agents that split a task into independent pieces, coordinate autonomously, and run concurrently.

In practice, agent teams look like a split-screen terminal environment: A developer can jump between subagents using Shift+Up/Down, take over any one directly, and watch the others keep working. Anthropic describes the feature as best suited for “tasks that split into independent, read-heavy work like codebase reviews.” It is available as a research preview.

OpenAI, meanwhile, released Frontier, an enterprise platform it describes as a way to “hire AI co-workers who take on many of the tasks people already do on a computer.” Frontier assigns each AI agent its own identity, permissions, and memory, and it connects to existing business systems such as CRMs, ticketing tools, and data warehouses. “What we’re fundamentally doing is basically transitioning agents into true AI co-workers,” Barret Zoph, OpenAI’s general manager of business-to-business, told CNBC.

Despite the hype about these agents being co-workers, from our experience, these agents tend to work best if you think of them as tools that amplify existing skills, not as the autonomous co-workers the marketing language implies. They can produce impressive drafts fast but still require constant human course-correction.

The Frontier launch came just three days after OpenAI released a new macOS desktop app for Codex, its AI coding tool, which OpenAI executives described as a “command center for agents.” The Codex app lets developers run multiple agent threads in parallel, each working on an isolated copy of a codebase via Git worktrees.

OpenAI also released GPT-5.3-Codex on Thursday, a new AI model that powers the Codex app. OpenAI claims that the Codex team used early versions of GPT-5.3-Codex to debug the model’s own training run, manage its deployment, and diagnose test results, similar to what OpenAI told Ars Technica in a December interview.

“Our team was blown away by how much Codex was able to accelerate its own development,” the company wrote. On Terminal-Bench 2.0, the agentic coding benchmark, GPT-5.3-Codex scored 77.3%, which exceeds Anthropic’s just-released Opus 4.6 by about 12 percentage points.

The common thread across all of these products is a shift in the user’s role. Rather than merely typing a prompt and waiting for a single response, the developer or knowledge worker becomes more like a supervisor, dispatching tasks, monitoring progress, and stepping in when an agent needs direction.

In this vision, developers and knowledge workers effectively become middle managers of AI. That is, not writing the code or doing the analysis themselves, but delegating tasks, reviewing output, and hoping the agents underneath them don’t quietly break things. Whether that will come to pass (or if it’s actually a good idea) is still widely debated.

A new model under the Claude hood

Opus 4.6 is a substantial update to Anthropic’s flagship model. It succeeds Claude Opus 4.5, which Anthropic released in November. In a first for the Opus model family, it supports a context window of up to 1 million tokens (in beta), which means it can process much larger bodies of text or code in a single session.

On benchmarks, Anthropic says Opus 4.6 tops OpenAI’s GPT-5.2 (an earlier model than the one released today) and Google’s Gemini 3 Pro across several evaluations, including Terminal-Bench 2.0 (an agentic coding test), Humanity’s Last Exam (a multidisciplinary reasoning test), and BrowseComp (a test of finding hard-to-locate information online)

Although it should be noted that OpenAI’s GPT-5.3-Codex, released the same day, seemingly reclaimed the lead on Terminal-Bench. On ARC AGI 2, which attempts to test the ability to solve problems that are easy for humans but hard for AI models, Opus 4.6 scored 68.8 percent, compared to 37.6 percent for Opus 4.5, 54.2 percent for GPT-5.2, and 45.1 percent for Gemini 3 Pro.

As always, take AI benchmarks with a grain of salt, since objectively measuring AI model capabilities is a relatively new and unsettled science.

Anthropic also said that on a long-context retrieval benchmark called MRCR v2, Opus 4.6 scored 76 percent on the 1 million-token variant, compared to 18.5 percent for its Sonnet 4.5 model. That gap matters for the agent teams use case, since agents working across large codebases need to track information across hundreds of thousands of tokens without losing the thread.

Pricing for the API stays the same as Opus 4.5 at $5 per million input tokens and $25 per million output tokens, with a premium rate of $10/$37.50 for prompts that exceed 200,000 tokens. Opus 4.6 is available on claude.ai, the Claude API, and all major cloud platforms.

The market fallout outside

These releases occurred during a week of exceptional volatility for software stocks. On January 30, Anthropic released 11 open source plugins for Cowork, its agentic productivity tool that launched on January 12. Cowork itself is a general-purpose tool that gives Claude access to local folders for work tasks, but the plugins extended it into specific professional domains: legal contract review, non-disclosure agreement triage, compliance workflows, financial analysis, sales, and marketing.

By Tuesday, investors reportedly reacted to the release by erasing roughly $285 billion in market value across software, financial services, and asset management stocks. A Goldman Sachs basket of US software stocks fell 6 percent that day, its steepest single-session decline since April’s tariff-driven sell-off. Thomson Reuters led the rout with an 18 percent drop, and the pain spread to European and Asian markets.

The purported fear among investors centers on AI model companies packaging complete workflows that compete with established software-as-a-service (SaaS) vendors, even if the verdict is still out on whether these tools can achieve those tasks.

OpenAI’s Frontier might deepen that concern: its stated design lets AI agents log in to applications, execute tasks, and manage work with minimal human involvement, which Fortune described as a bid to become “the operating system of the enterprise.” OpenAI CEO of Applications Fidji Simo pushed back on the idea that Frontier replaces existing software, telling reporters, “Frontier is really a recognition that we’re not going to build everything ourselves.”

Whether these co-working apps actually live up to their billing or not, the convergence is hard to miss. Anthropic’s Scott White, the company’s head of product for enterprise, gave the practice a name that is likely to roll a few eyes. “Everybody has seen this transformation happen with software engineering in the last year and a half, where vibe coding started to exist as a concept, and people could now do things with their ideas,” White told CNBC. “I think that we are now transitioning almost into vibe working.”

Benj Edwards

Senior AI Reporter

Benj Edwards

Senior AI Reporter

Benj Edwards

Senior AI Reporter

Benj Edwards

Senior AI Reporter

Google hints at big AirDrop expansion for Android "very soon"

There is very little functional difference between iOS and Android these days. The systems could integrate quite well if it weren't for the way companies prioritize lock-in over compatibility. At least in the realm of file sharing, Google is working to fix that. After adding basic AirDrop support to Pixel 10 devices last year, the company says we can look forward to seeing it on many more phones this year.

At present, the only Android phones that can initiate an AirDrop session with Apple devices are Google's latest Pixel 10 devices. When Google announced this upgrade, it vaguely suggested that more developments would come, and it now looks like we'll see more AirDrop support soon.

According to Android Authority, Google is planning a big AirDrop expansion in 2026. During an event at the company's Taipei office, Eric Kay, Google's VP of engineering for Android, laid out the path ahead.

OpenAI is hoppin' mad about Anthropic's new Super Bowl TV ads

OpenAI is hoppin’ mad about Anthropic’s new Super Bowl TV ads

Sam Altman calls AI competitor “dishonest” and “authoritarian” in lengthy post on X.

Learn more

On Wednesday, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman and Chief Marketing Officer Kate Rouch complained on X after rival AI lab Anthropic released four commercials, two of which will run during the Super Bowl on Sunday, mocking the idea of including ads in AI chatbot conversations. Anthropic’s campaign seemingly touched a nerve at OpenAI just weeks after the ChatGPT maker began testing ads in a lower-cost tier of its chatbot.

Altman called Anthropic’s ads “clearly dishonest,” accused the company of being “authoritarian,” and said it “serves an expensive product to rich people,” while Rouch wrote, “Real betrayal isn’t ads. It’s control.”

Anthropic’s four commercials, part of a campaign called “A Time and a Place,” each open with a single word splashed across the screen: “Betrayal,” “Violation,” “Deception,” and “Treachery.” They depict scenarios where a person asks a human stand-in for an AI chatbot for personal advice, only to get blindsided by a product pitch.

In one spot, a man asks a therapist-style chatbot (a woman sitting in a chair) how to communicate better with his mom. The bot offers a few suggestions, then pivots to promoting a fictional cougar-dating site called Golden Encounters.

In another spot, a skinny man looking for fitness tips instead gets served an ad for height-boosting insoles. Each ad ends with the tagline: “Ads are coming to AI. But not to Claude.” Anthropic plans to air a 30-second version during Super Bowl LX, with a 60-second cut running in the pregame, according to CNBC.

In the X posts, the OpenAI executives argue that these commercials are misleading because the planned ChatGPT ads will appear labeled at the bottom of conversational responses in banners and will not alter the chatbot’s answers.

But there’s a slight twist: OpenAI’s own blog post about its ad plans states that the company will “test ads at the bottom of answers in ChatGPT when there’s a relevant sponsored product or service based on your current conversation,” meaning the ads will be conversation-specific.

The financial backdrop explains some of the tension over ads in chatbots. As Ars previously reported, OpenAI struck more than $1.4 trillion in infrastructure deals in 2025 and expects to burn roughly $9 billion this year while generating about $13 billion in revenue. Only about 5 percent of ChatGPT’s 800 million weekly users pay for subscriptions. Anthropic is also not yet profitable, but it relies on enterprise contracts and paid subscriptions rather than advertising, and it has not taken on infrastructure commitments at the same scale as OpenAI.

Three OpenAI leaders weigh in

Competition between Anthropic and OpenAI is especially testy because several OpenAI employees left the company to found Anthropic in 2021. Currently, Anthropic’s Claude Code has pulled off something of a market upset, becoming a favorite among some software developers despite the company’s much smaller overall market share among chatbot users.

Altman opened his lengthy post on X by granting that the ads were “funny” and that he “laughed.” But then the tone shifted. “I wonder why Anthropic would go for something so clearly dishonest,” he wrote. “We would obviously never run ads in the way Anthropic depicts them. We are not stupid and we know our users would reject that.”

He went further: “I guess it’s on brand for Anthropic doublespeak to use a deceptive ad to critique theoretical deceptive ads that aren’t real, but a Super Bowl ad is not where I would expect it.”

Altman framed the dispute as a fight over access. “More Texans use ChatGPT for free than total people use Claude in the US, so we have a differently shaped problem than they do,” he wrote. He then accused Anthropic of overreach: “Anthropic wants to control what people do with AI,” adding that Anthropic blocks “companies they don’t like from using their coding product (including us).” He closed with: “One authoritarian company won’t get us there on their own, to say nothing of the other obvious risks. It is a dark path.”

OpenAI CMO Kate Rouch posted a response, calling the ads “funny” before pivoting. “Anthropic thinks powerful AI should be tightly controlled in small rooms in San Francisco and Davos,” she wrote. “That it’s too DANGEROUS for you.”

Anthropic’s post declaring Claude ad-free does hedge a bit, however. “Should we need to revisit this approach, we’ll be transparent about our reasons for doing so,” Anthropic wrote.

OpenAI President Greg Brockman pointed this out on X, asking Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei directly whether he would “commit to never selling Claude’s ‘users’ attention or data to advertisers,’” calling it a “genuine question” and noting that Anthropic’s blog post “makes it sound like you’re keeping the option open.”

Benj Edwards

Senior AI Reporter

Benj Edwards

Senior AI Reporter

Benj Edwards

Senior AI Reporter

Benj Edwards

Senior AI Reporter

Steam Machine and Steam Frame delays are the latest product of the RAM crisis

When Valve announced its Steam Machine desktop PC and Steam Frame VR headset in mid-November of last year, it declined to announce pricing or availability information for either device. That was partly because RAM and storage prices had already begun to climb, thanks to shortages caused by the AI industry's insatiable need for memory. Those price spikes have only gotten worse since then, and they're beginning to trickle down to GPUs and other devices that use memory chips.

This week, Valve has officially announced that it's still not ready to make an official announcement about when the Machine or Frame will be available or what they'll cost.

Valve says it still plans to launch both devices (as well as the new Steam Controller) "in the first half of the year," but that uncertainty around RAM and storage prices mean that Valve "[has] work to do to land on concrete pricing and launch dates we can confidently announce, being mindful of how quickly the circumstances around both of these things can change."

Increase of AI bots on the Internet sparks arms race

Increase of AI bots on the Internet sparks arms race

Publishers are rolling out more aggressive defenses.

Credit:

dakuq via Getty

Credit:

dakuq via Getty

Story text

Size

Small

Standard

Large

Width

*

Standard

Wide

Links

Standard

Orange

* Subscribers only

Credit:

dakuq via Getty

Credit:

dakuq via Getty

Story text

Size

Small

Standard

Large

Width

*

Standard

Wide

Links

Standard

Orange

* Subscribers onlyLearn more

The viral virtual assistant OpenClaw—formerly known as Moltbot, and before that Clawdbot—is a symbol of a broader revolution underway that could fundamentally alter how the Internet functions. Instead of a place primarily inhabited by humans, the web may very soon be dominated by autonomous AI bots.

A new report measuring bot activity on the web, as well as related data shared with WIRED by the Internet infrastructure company Akamai, shows that AI bots already account for a meaningful share of web traffic. The findings also shed light on an increasingly sophisticated arms race unfolding as bots deploy clever tactics to bypass website defenses meant to keep them out.

“The majority of the Internet is going to be bot traffic in the future,” says Toshit Pangrahi, cofounder and CEO of TollBit, a company that tracks web-scraping activity and published the new report. “It’s not just a copyright problem, there is a new visitor emerging on the Internet.”

Most big websites try to limit what content bots can scrape and feed to AI systems for training purposes. (WIRED’s parent company, Condé Nast, as well as other publishers, are currently suing several AI companies over alleged copyright infringement related to AI training.)

But another kind of AI-related website scraping is now on the rise as well. Many chatbots and other AI tools can now retrieve real-time information from the web and use it to augment and improve their outputs. This might include up-to-the-minute product prices, movie theater schedules, or summaries of the latest news.

According to the data from Akamai, training-related bot traffic has been rising steadily since last July. Meanwhile, global activity from bots fetching web content for AI agents is also on the upswing.

“AI is changing the web as we know it,” Robert Blumofe, Akamai’s chief technology officer, tells WIRED. “The ensuing arms race will determine the future look, feel, and functionality of the web, as well as the basics of doing business.”

In the fourth quarter of 2025, TollBit estimates that an average of one out of every 31 visits to its customers’ websites was from an AI scraping bot. In the first quarter, that figure was only one out of every 200. The company says that in the fourth quarter, more than 13 percent of bot requests were bypassing robots.txt, a file that some websites use to indicate which pages bots are supposed to avoid. TollBit says the share of AI bots disregarding robots.txt increased 400 percent from the second quarter to the fourth quarter of last year.

TollBit also reported a 336 percent increase in the number of websites making attempts to block AI bots over the past year. Pangrahi says that scraping techniques are getting more sophisticated as sites try to assert control over how bots access their content. Some bots disguise themselves by making their traffic appear like it’s coming from a normal web browser or send requests designed to mimic how humans normally interact with websites. TollBit’s study notes that the behavior of some AI agents is now almost indistinguishable from human web traffic.

TollBit markets tools that website owners can use to charge AI scrapers for accessing their content. Other firms, including Cloudflare, offer similar tools. “Anyone who relies on human web traffic—starting with publishers, but basically everyone—is going to be impacted,” Pangrahi says. “There needs to be a faster way to have that machine-to-machine, programmatic exchange of value.”

WIRED attempted to contact 15 AI scraping companies cited in the TollBit report for comment. The majority did not respond or could not be reached. Several said that their AI systems aim to respect technical boundaries that websites put in place to limit scraping, but they noted such guardrails can often be complex and difficult to follow.

Or Lenchner, the CEO of Bright Data, one of the world’s largest web-scraping firms, says that his company’s bots do not collect nonpublic information. Bright Data was previously sued by Meta and X for allegedly improperly scraping content from their platforms. (Meta later dropped its suit, and a federal judge in California dismissed the case brought by X.)

Karolis Stasiulevičiu, a spokesperson for another cited company, ScrapingBee, told WIRED: “ScrapingBee operates on one of the Internet’s core principles: that the open web is meant to be accessible. Public web pages are, by design, readable by both humans and machines.”

Oxylabs, another scraping firm, said in an unsigned statement that its bots don’t have “access to content behind logins, paywalls, or authentication. We require customers to use our services only for accessing publicly available information, and we enforce compliance standards throughout our platform.”

Oxylabs added that there are many legitimate reasons for firms to scrape web content, including for cybersecurity purposes and to conduct investigative journalism. The company also says that the countermeasures some websites use do not discriminate between different use cases. “The reality is that many modern anti-bot systems don’t distinguish well between malicious traffic and legitimate automated access,” Oxylabs says.

In addition to causing headaches for publishers, the web-scraping wars are creating new business opportunities. TollBit’s report found more than 40 companies that are now marketing bots that can collect web content for AI training or other purposes. The rise of AI-powered search engines, as well as tools like OpenClaw, are likely helping drive up demand for these services.

Some firms promise to help companies surface content for AI agents rather than try to block them, a strategy known as generative engine optimization, or GEO. “We’re essentially seeing the rise of a new marketing channel,” says Uri Gafni, chief business officer of Brandlight, a company that optimizes content so that it appears prominently in AI tools.

“This will only intensify in 2026, and we’re going to see this rollout kind of as a full-on marketing channel, with search, ads, media, and commerce converging,” Gafni says.

This story originally appeared on wired.com.

Microsoft releases urgent Office patch. Russian-state hackers pounce.

Microsoft releases urgent Office patch. Russian-state hackers pounce.

The window to patch vulnerabilities is shrinking rapidly.

Credit:

Getty Images

Credit:

Getty Images

Story text

Size

Small

Standard

Large

Width

*

Standard

Wide

Links

Standard

Orange

* Subscribers only

Credit:

Getty Images

Credit:

Getty Images

Story text

Size

Small

Standard

Large

Width

*

Standard

Wide

Links

Standard

Orange

* Subscribers onlyLearn more

Russian-state hackers wasted no time exploiting a critical Microsoft Office vulnerability that allowed them to compromise the devices inside diplomatic, maritime, and transport organizations in more than half a dozen countries, researchers said Wednesday.

The threat group, tracked under names including APT28, Fancy Bear, Sednit, Forest Blizzard, and Sofacy, pounced on the vulnerability, tracked as CVE-2026-21509, less than 48 hours after Microsoft released an urgent, unscheduled security update late last month, the researchers said. After reverse-engineering the patch, group members wrote an advanced exploit that installed one of two never-before-seen backdoor implants.

Stealth, speed, and precision

The entire campaign was designed to make the compromise undetectable to endpoint protection. Besides being novel, the exploits and payloads were encrypted and ran in memory, making their malice hard to spot. The initial infection vector came from previously compromised government accounts from multiple countries and were likely familiar to the targeted email holders. Command and control channels were hosted in legitimate cloud services that are typically allow-listed inside sensitive networks.

“The use of CVE-2026-21509 demonstrates how quickly state-aligned actors can weaponize new vulnerabilities, shrinking the window for defenders to patch critical systems,” the researchers, with security firm Trellix, wrote. “The campaign’s modular infection chain—from initial phish to in-memory backdoor to secondary implants was carefully designed to leverage trusted channels (HTTPS to cloud services, legitimate email flows) and fileless techniques to hide in plain sight.”

The 72-hour spear phishing campaign began January 28 and delivered at least 29 distinct email lures to organizations in nine countries, primarily in Eastern Europe. Trellix named eight of them: Poland, Slovenia, Turkey, Greece, the UAE, Ukraine, Romania, and Bolivia. Organizations targeted were defense ministries (40 percent), transportation/logistics operators (35 percent), and diplomatic entities (25 percent).

The infection chain resulted in the installation of BeardShell or NotDoor, the tracking names Trellix has given to the novel backdoors. BeardShell gave the group full system reconnaissance, persistence through injecting processes into Windows svchost.exe, and an opening for lateral movement to other systems inside an infected network. The implant was executed through dynamically loaded .NET assemblies that left no disk-based forensic artifacts beyond memory from the resident code injection.

NotDoor came in the form of a VBA macro and was installed only after the exploit chain disabled Outlook’s macro security controls. Once installed, the implant monitored email folders, including Inbox, Drafts, Junk Mail, and RSS Feeds. It bundled messages into a Windows .msg file, which would then be sent to attacker-controlled accounts set up on cloud service filen.io. To defeat security controls on high-privilege accounts that are designed to restrict access to classified cables and other sensitive documents, the macro processed emails with a custom “AlreadyForwarded” property and set “DeleteAfterSubmit” to true to purge forwarded messages from the Sent Items folder.

Trellix attributed the campaign to APT28 with “high confidence” based on technical indicators and the targets selected. Ukraine’s CERT-UA has also attributed the attacks to UAC-0001, a tracking name that corresponds to APT28.

“APT28 has a long history of cyber espionage and influence operations,” Trellix wrote. “The tradecraft in this campaign—multi-stage malware, extensive obfuscation, abuse of cloud services, and targeting of email systems for persistence—reflects a well-resourced, advanced adversary consistent with APT28’s profile. The toolset and techniques also align with APT28’s fingerprint.”

Trellix has provided a comprehensive list of indicators organizations can use to determine if they have been targeted.

Dan Goodin

Senior Security Editor

Dan Goodin

Senior Security Editor

Dan Goodin

Senior Security Editor

Dan Goodin

Senior Security Editor

Should AI chatbots have ads? Anthropic says no.

Should AI chatbots have ads? Anthropic says no.

ChatGPT competitor comes out swinging with Super Bowl ad mocking AI product pitches.

Credit:

Anthropic

Credit:

Anthropic

Story text

Size

Small

Standard

Large

Width

*

Standard

Wide

Links

Standard

Orange

* Subscribers only

Credit:

Anthropic

Credit:

Anthropic

Story text

Size

Small

Standard

Large

Width

*

Standard

Wide

Links

Standard

Orange

* Subscribers onlyLearn more

On Wednesday, Anthropic announced that its AI chatbot, Claude, will remain free of advertisements, drawing a sharp line between itself and rival OpenAI, which began testing ads in a low-cost tier of ChatGPT last month. The announcement comes alongside a Super Bowl ad campaign that mocks AI assistants that interrupt personal conversations with product pitches.

“There are many good places for advertising. A conversation with Claude is not one of them,” Anthropic wrote in a blog post. The company argued that including ads in AI conversations would be “incompatible” with what it wants Claude to be: “a genuinely helpful assistant for work and for deep thinking.”

The stance contrasts with OpenAI’s January announcement that it would begin testing banner ads for free users and ChatGPT Go subscribers in the US. OpenAI said those ads would appear at the bottom of responses and would not influence the chatbot’s actual answers. Paid subscribers on Plus, Pro, Business, and Enterprise tiers will not see ads on ChatGPT.

“We want Claude to act unambiguously in our users’ interests,” Anthropic wrote. “So we’ve made a choice: Claude will remain ad-free. Our users won’t see ‘sponsored’ links adjacent to their conversations with Claude; nor will Claude’s responses be influenced by advertisers or include third-party product placements our users did not ask for.”

Competition between OpenAI and Anthropic has been fierce of late, due to the rise of AI coding agents. Claude Code, Anthropic’s coding tool, and OpenAI’s Codex have similar capabilities, but Claude Code has been widely popular among developers and is closing in on OpenAI’s turf. Last month, The Verge reported that many developers inside long-time OpenAI benefactor Microsoft have been adopting Claude Code, choosing Anthropic products over Microsoft’s Copilot, which is powered by tech that originated at OpenAI.

In this climate, Anthropic could not resist taking a dig at OpenAI. In its Super Bowl commercial, we see a thin man struggling to do a pull-up beside a buff fitness instructor, who is a stand-in for an AI assistant. The man asks the “assistant” for help making a workout plan, but the assistant slips in an advertisement for a supplement, confusing the man. The commercial doesn’t name any names, and OpenAI has said it will not include ads in chat text itself, but Anthropic’s implications are clear.

Different incentives, different futures

In its blog post, Anthropic describes internal analysis it conducted that suggests many Claude conversations involve topics that are “sensitive or deeply personal” or require sustained focus on complex tasks. In these contexts, Anthropic wrote, “The appearance of ads would feel incongruous—and, in many cases, inappropriate.”

The company also argued that advertising introduces incentives that could conflict with providing genuinely helpful advice. It gave the example of a user mentioning trouble sleeping: an ad-free assistant would explore various causes, while an ad-supported one might steer the conversation toward a transaction.

“Users shouldn’t have to second-guess whether an AI is genuinely helping them or subtly steering the conversation towards something monetizable,” Anthropic wrote.

Currently, OpenAI does not plan to include paid product recommendations within a ChatGPT conversation. Instead, the ads appear as banners alongside the conversation text.

OpenAI CEO Sam Altman has previously expressed reservations about mixing ads and AI conversations. In a 2024 interview at Harvard University, he described the combination as “uniquely unsettling” and said he would not like having to “figure out exactly how much was who paying here to influence what I’m being shown.”

A key part of Altman’s partial change of heart is that OpenAI faces enormous financial pressure. The company made more than $1.4 trillion worth of infrastructure deals in 2025, and according to documents obtained by The Wall Street Journal, it expects to burn through roughly $9 billion this year while generating $13 billion in revenue. Only about 5 percent of ChatGPT’s 800 million weekly users pay for subscriptions.

Much like OpenAI, Anthropic is not yet profitable, but it is expected to get there much faster. Anthropic has not attempted to span the world with massive datacenters, and its business model largely relies on enterprise contracts and paid subscriptions. The company says Claude Code and Cowork have already brought in at least $1 billion in revenue, according to Axios.

“Our business model is straightforward,” Anthropic wrote. “This is a choice with tradeoffs, and we respect that other AI companies might reasonably reach different conclusions.”

Benj Edwards

Senior AI Reporter

Benj Edwards

Senior AI Reporter

Benj Edwards

Senior AI Reporter

Benj Edwards

Senior AI Reporter

User blowback convinces Adobe to keep supporting 30-year-old 2D animation app

Adobe has canceled plans to discontinue its 2D animation software Animate.

On Monday, Adobe announced that it would stop allowing people to sell subscriptions to Animate on March 1, saying the software had “served its purpose." People who already had a software license would be able to keep using Animate with technical support until March 1, 2027; businesses had until March 1, 2029. Per an email sent to customers, Adobe also said users would lose access to Animate files and project data on March 1, 2027. Animate costs $23 per month.

After receiving backlash from animators and other users, Adobe reversed its decision on Tuesday night. In an announcement posted online, the San Jose, California-headquartered company said:

So yeah, I vibe-coded a log colorizer—and I feel good about it

So yeah, I vibe-coded a log colorizer—and I feel good about it

Some semi-unhinged musings on where LLMs fit into my life—and how I’ll keep using them.

Learn more

I can’t code.

I know, I know—these days, that sounds like an excuse. Anyone can code, right?! Grab some tutorials, maybe an O’Reilly book, download an example project, and jump in. It’s just a matter of learning how to break your project into small steps that you can make the computer do, then memorizing a bit of syntax. Nothing about that is hard!

Perhaps you can sense my sarcasm (and sympathize with my lack of time to learn one more technical skill).

Oh, sure, I can “code.” That is, I can flail my way through a block of (relatively simple) pseudocode and follow the flow. I have a reasonably technical layperson’s understanding of conditionals and loops, and of when one might use a variable versus a constant. On a good day, I could probably even tell you what a “pointer” is.

But pulling all that knowledge together and synthesizing a working application any more complex than “hello world”? I am not that guy. And at this point, I’ve lost the neuroplasticity and the motivation (if I ever had either) to become that guy.

Thanks to AI, though, what has been true for my whole life need not be true anymore. Perhaps, like my colleague Benj Edwards, I can whistle up an LLM or two and tackle the creaky pile of “it’d be neat if I had a program that would do X” projects without being publicly excoriated on StackOverflow by apex predator geeks for daring to sully their holy temple of knowledge with my dirty, stupid, off-topic, already-answered questions.

So I gave it a shot.

A cache-related problem appears

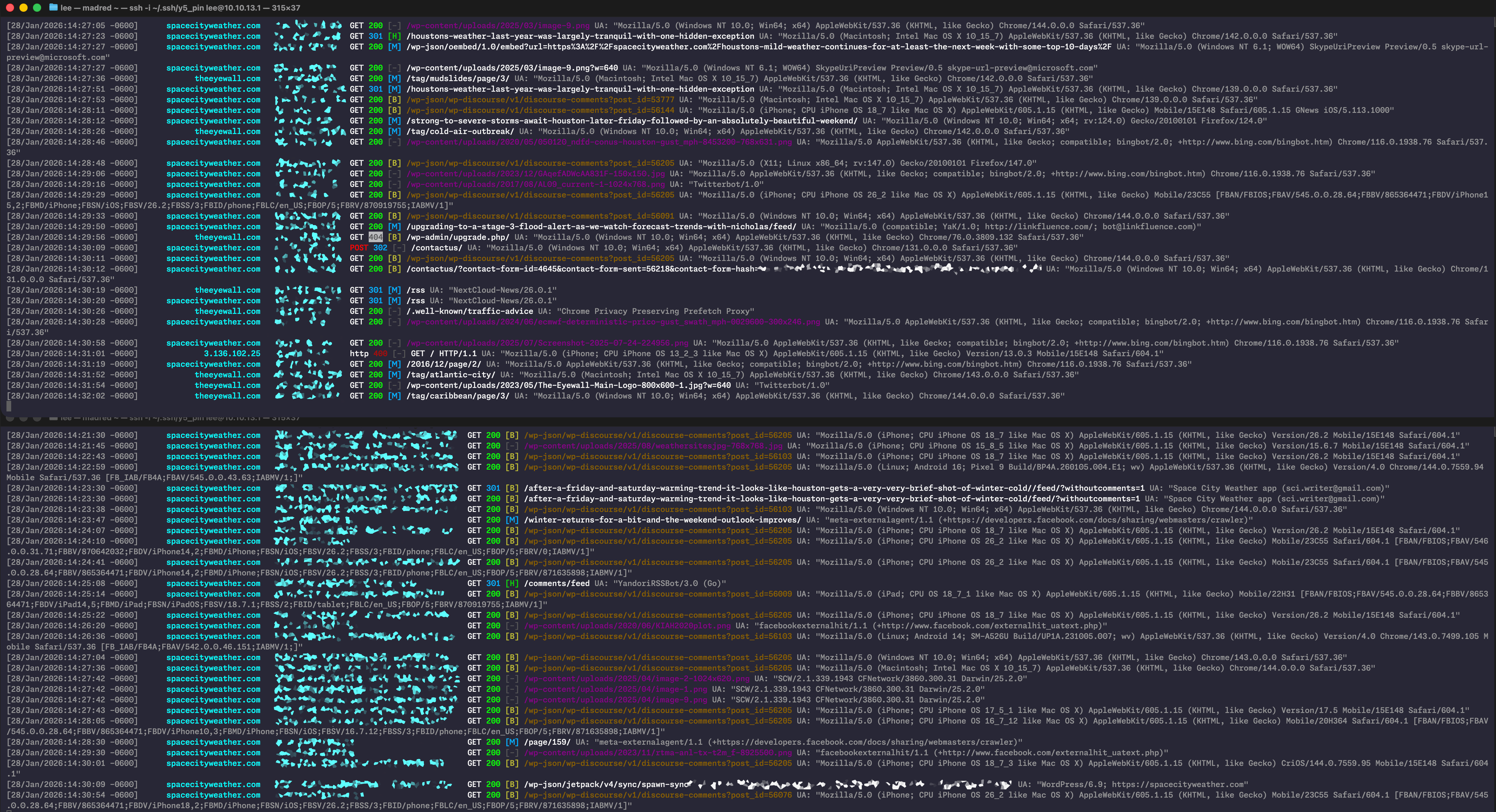

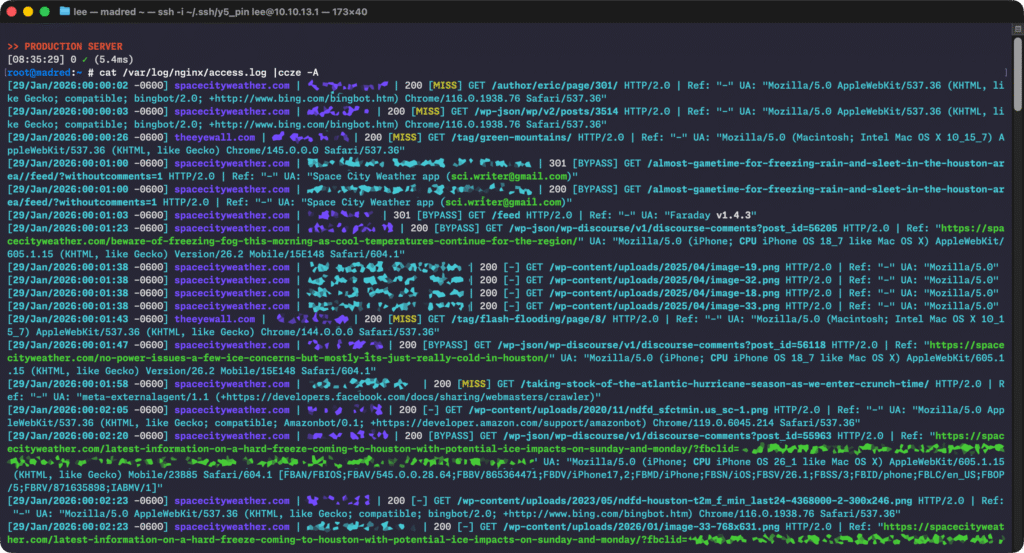

My project is a small Python-based log colorizer that I asked Claude Code to construct for me. If you’d like to peek at the code before listening to me babble, a version of the project without some of the Lee-specific customizations is available on GitHub.

Why a log colorizer? Two reasons. First, and most important to me, because I needed to look through a big ol’ pile of web server logs, and off-the-shelf colorizer solutions weren’t customizable to the degree I wanted. Vibe-coding one that exactly matched my needs made me happy.

But second, and almost equally important, is that this was a small project. The colorizer ended up being a 400-ish line, single-file Python script. The entire codebase, plus the prompting and follow-up instructions, fit easily within Claude Code’s context window. This isn’t an application that sprawls across dozens or hundreds of functions in multiple files, making it easy to audit (even for me).

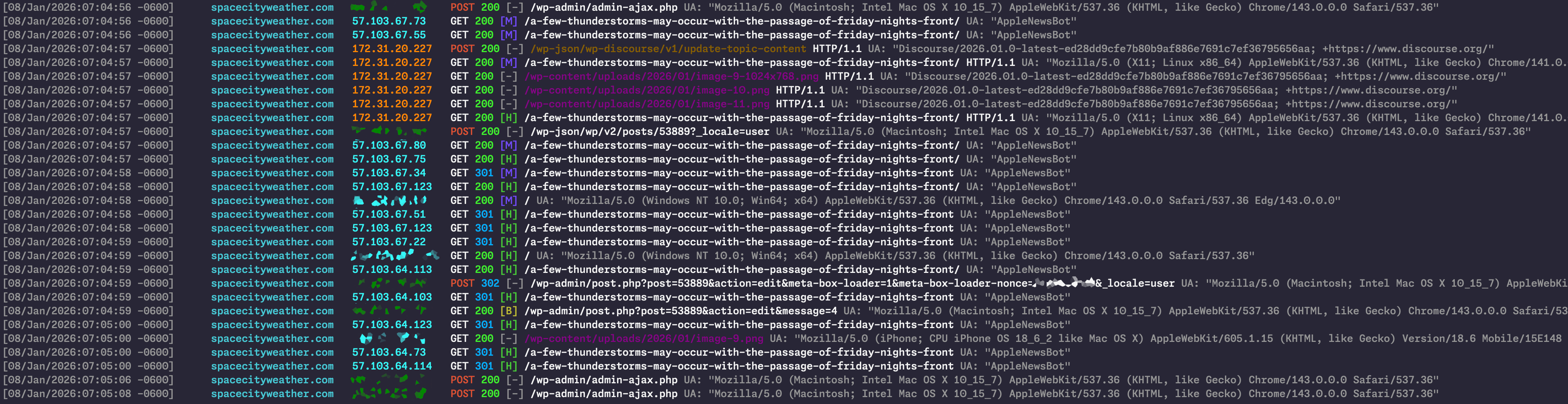

Setting the stage: I do the web hosting for my colleague Eric Berger’s Houston-area forecasting site, Space City Weather. It’s a self-hosted WordPress site, running on an AWS EC2 t3a.large instance, fronted by Cloudflare using CF’s WordPress Automatic Platform Optimization.

Space City Weather also uses self-hosted Discourse for commenting, replacing WordPress’ native comments at the bottom of Eric’s daily weather posts via the WP-Discourse plugin. Since bolting Discourse onto the site back in August 2025, though, I’ve had an intermittent issue where sometimes—but not all the time—a daily forecast post would go live and get cached by Cloudflare with the old, disabled native WordPress comment area attached to the bottom instead of the shiny new Discourse comment area. Hundreds of visitors would then see a version of the post without a functional comment system until I manually expired the stale page or until the page hit Cloudflare’s APO-enforced max age and expired itself.

The problem behavior would lie dormant for weeks or months, and then we’d get a string of back-to-back days where it would rear its ugly head. Edge cache invalidation on new posts is supposed to be triggered automatically by the official Cloudflare WordPress plug-in, and indeed, it usually worked fine—but “usually” is not “always.”

In the absence of any obvious clues as to why this was happening, I consulted a few different LLMs and asked for possible fixes. The solution I settled on was having one of them author a small mu-plugin in PHP (more vibe coding!) that forces WordPress to slap “DO NOT CACHE ME!” headers on post pages until it has verified that Discourse has hooked its comments to the post. (Curious readers can put eyes on this plugin right here.)

This “solved” the problem by preempting the problem behavior, but it did nothing to help me identify or fix the actual underlying issue. I turned my attention elsewhere for a few months. One day in December, as I was updating things, I decided to temporarily disable the mu-plugin to see if I still needed it. After all, problems sometimes go away on their own, right? Computers are crazy!

Alas, the next time Eric made a Space City Weather post, it popped up sans Discourse comment section, with the (ostensibly disabled) WordPress comment form at the bottom. Clearly, the problem behavior was still in play.

Interminable intermittence

Have you ever been stuck troubleshooting an intermittent issue? Something doesn’t work, you make a change, it suddenly starts working, then despite making no further changes, it randomly breaks again.

The process makes you question basic assumptions, like, “Do I actually know how to use a computer?” You feel like you might be actually-for-real losing your mind. The final stage of this process is the all-consuming death spiral, where you start asking stuff like, “Do I need to troubleshoot my troubleshooting methods? Is my server even working? Is the simulation we’re all living in finally breaking down and reality itself is toying with me?!”

In this case, I couldn’t reproduce the problem behavior on demand, no matter how many tests I tried. I couldn’t see any narrow, definable commonalities between days where things worked fine and days where things broke.

My best hope for getting a handle on the problem likely lay deeply buried in the server’s logs. Like any good sysadmin, I gave the logs a quick once-over for problems a couple of times per month, but Space City Weather is a reasonably busy medium-sized site and dishes out its daily forecast to between 20,000 and 30,000 people (“unique visitors” in web parlance, or “UVs” if you want to sound cool). Even with Cloudflare taking the brunt of the traffic, the daily web server log files are, let us say, “a bit dense.” My surface-level glances weren’t doing the trick—I’d have to actually dig in. And having been down this road before for other issues, I knew I needed more help than grep alone could provide.

The vibe use case

The Space City Weather web server uses Nginx for actual web serving. For folks who have never had the pleasure, Nginx, as configured in most of its distributable packages, keeps a pair of log files around—one that shows every request serviced and another just for errors.

I wanted to watch the access log right when Eric was posting to see if anything obviously dumb/bad/wrong/broken was happening. But I’m not super-great at staring at a giant wall of text and symbols, and I tend to lean heavily on syntax highlighting and colorization to pick out the important bits when I’m searching through log files. There’s an old and crusty program called ccze that’s easily findable in most repos; I’ve used it forever, and if its default output does what you need, then it’s an excellent tool.

But customizing ccze’s output is a “here be dragons”-type task. The application is old, and time has ossified it into something like an unapproachably evil Mayan relic, filled with shadowy regexes and dark magic, fit to be worshipped from afar but not trifled with. Altering ccze’s behavior threatens to become an effort-swallowing bottomless pit, where you spend more time screwing around with the tool and the regexes than you actually spend using the tool to diagnose your original problem.

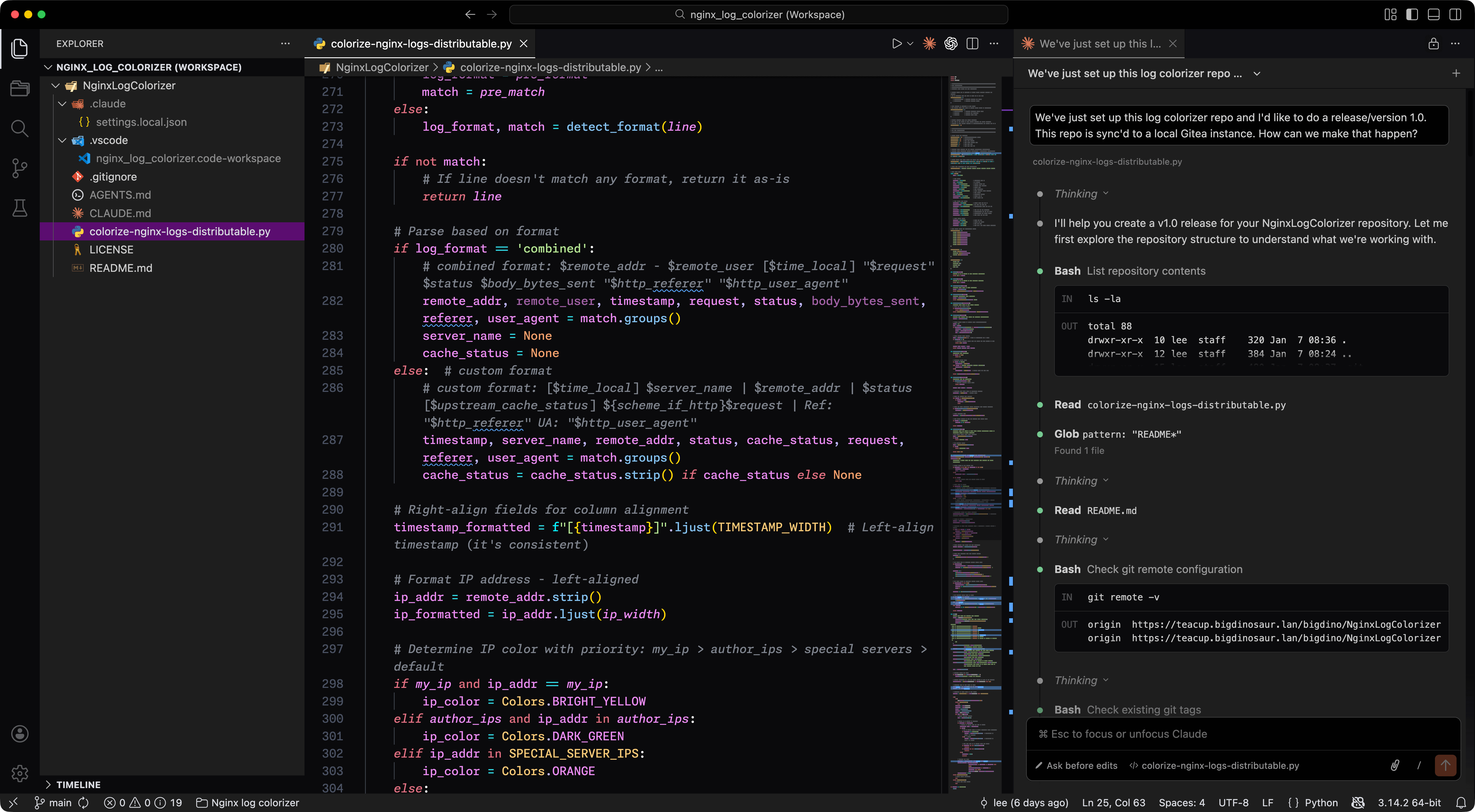

It was time to fire up VSCode and pretend to be a developer. I set up a new project, performed the demonic invocation to summon Claude Code, flipped the thing into “plan mode,” and began.

“I’d like to see about creating an Nginx log colorizer,” I wrote in the prompt box. “I don’t know what language we should use. I would like to prioritize efficiency and performance in the code, as I will be running this live in production and I can’t have it adding any applicable load.” I dropped a truncated, IP-address-sanitized copy of yesterday’s Nginx access.log into the project directory.

“See the access.log file in the project directory as an example of the data we’ll be colorizing. You can test using that file,” I wrote.

Ever helpful, Claude Code chewed on the prompt and the example data for a few seconds, then began spitting output. It suggested Python for our log colorizer because of the language’s mature regex support—and to keep the code somewhat readable for poor, dumb me. The actual “vibe-coding” wound up spanning two sessions over two days, as I exhausted my Claude Code credits on the first one (a definite vibe-coding danger!) and had to wait for things to reset.

“Dude, lnav and Splunk exist, what is wrong with you?”

Yes, yes, a log colorizer is bougie and lame, and I’m treading over exceedingly well-trodden ground. I did, in fact, sit for a bit with existing tools—particularly lnav, which does most of what I want. But I didn’t want most of my requirements met. I wanted all of them. I wanted a bespoke tool, and I wanted it without having to pay the “is it worth the time?” penalty. (Or, perhaps, I wanted to feel like the LLM’s time was being wasted rather than mine, given that the effort ultimately took two days of vibe-coding.)

And about those two days: Getting a basic colorizer coded and working took maybe 10 minutes and perhaps two rounds of prompts. It was super-easy. Where I burned the majority of the time and compute power was in tweaking the initial result to be exactly what I wanted.

For therein lies the truly seductive part of vibe-coding—the ease of asking the LLM to make small changes or improvements and the apparent absence of cost or consequence for implementing those changes. The impression is that you’re on the Enterprise-D, chatting with the ship’s computer, collaboratively solving a problem with Geordi and Data standing right behind you. It’s downright intoxicating to say, “Hm, yes, now let’s make it so I can show only IPv4 or IPv6 clients with a command line switch,” and the machine does it. (It’s even cooler if you make the request while swinging your leg over the back of a chair so you can sit in it Riker-style!)

It’s exhilarating, honestly, in an Emperor Palpatine “UNLIMITED POWERRRRR!” kind of way. It removes a barrier that I didn’t think would ever be removed—or, rather, one I thought I would never have the time, motivation, or ability to tear down myself.

In the end, after a couple of days of testing and iteration—including a couple of “Is this colorizer performant, and will it introduce system load if run in production?” back-n-forth exchanges where the LLM reduced the cost of our regex matching and ensured our main loop wasn’t very heavy, I got a tool that does exactly what I want.

Specifically, I now have a log colorizer that:

- Handles multiple Nginx (and Apache) log file formats

- Colorizes things using 256-color ANSI codes that look roughly the same in different terminal applications

- Organizes hostname & IP addresses in fixed-length columns for easy scanning

- Colorizes HTTP status codes and cache status (with configurable colors)

- Applies different colors to the request URI depending on the resource being requested

- Has specific warning colors and formatting to highlight non-HTTPS requests or other odd things

- Can apply alternate colors for specific IP addresses (so I can easily pick out Eric’s or my requests)

- Can constrain output to only show IPv4 or IPv6 hosts

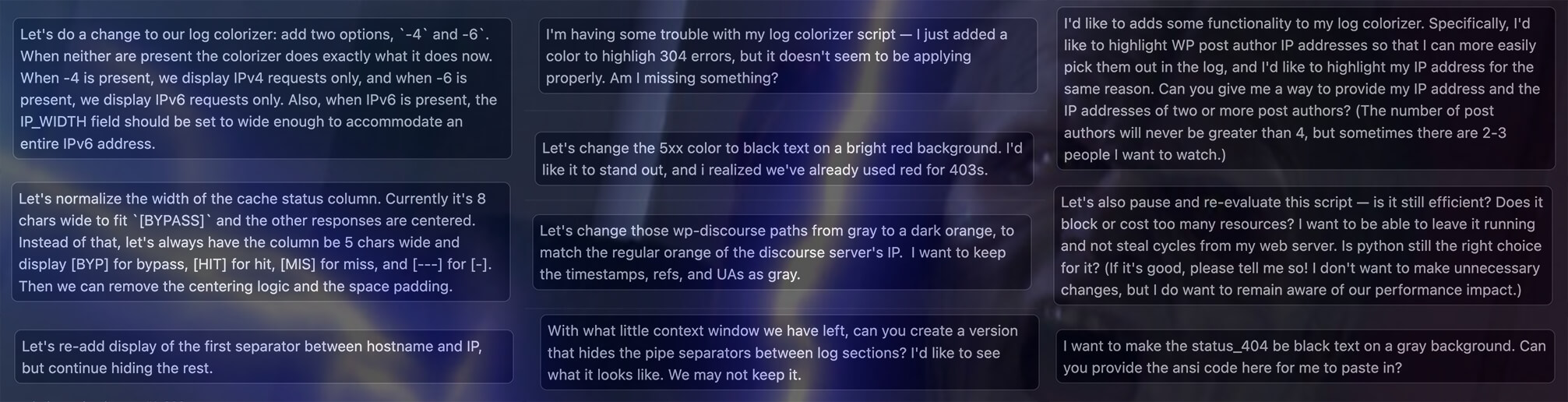

…and, worth repeating, it all looks exactly how I want it to look and behaves exactly how I want it to behave. Here’s another action shot!

Problem spotted

Armed with my handy-dandy log colorizer, I patiently waited for the wrong-comment-area problem behavior to re-rear its still-ugly head. I did not have to wait long, and within a couple of days, I had my root cause. It had been there all along, if I’d only decided to spend some time looking for it. Here it is:

Briefly: The problem is Apple’s fault. (Well, not really. But kinda.)

Less briefly: I’ve blurred out Eric’s IP address, but it’s dark green, so any place in the above image where you see a blurry, dark green smudge, that’s Eric. In the roughly 12-ish seconds presented here, you’re seeing Eric press the “publish” button on his daily forecast—that’s the “POST” event at the very top of the window. The subsequent events from Eric’s IP address are his browser having the standard post-publication conversation with WordPress so it can display the “post published successfully” notification and then redraw the WP block editor.

Below Eric’s post, you can see the Discourse server (with orange IP address) notifying WordPress that it has created a new Discourse comment thread for Eric’s post, then grabbing the things it needs to mirror Eric’s post as the opener for that thread. You can see it does GETs for the actual post and also for the post’s embedded images. About one second after Eric hits “publish,” the new post’s Discourse thread is ready, and it gets attached to Eric’s post.

Ah, but notice what else happens during that one second.

To help expand Space City Weather’s reach, we cross-publish all of the site’s posts to Apple News, using a popular Apple News plug-in (the same one Ars uses, in fact). And right there, with those two GET requests immediately after Eric’s POST request, lay the problem: You’re seeing the vanguard of Apple News’ hungry army of story-retrieval bots, summoned by the same “publish” event, charging in and demanding a copy of the brand new post before Discourse has a chance to do its thing.

It was a classic problem in computing: a race condition. Most days, Discourse’s new thread creation would beat the AppleNewsBot rush; some days, though, it wouldn’t. On the days when it didn’t, the horde of Apple bots would demand the page before its Discourse comments were attached, and Cloudflare would happily cache what those bots got served.

I knew my fix of emitting “NO CACHE” headers on the story pages prior to Discourse attaching comments worked, but now I knew why it worked—and why the problem existed in the first place. And oh, dear reader, is there anything quite so viscerally satisfying in all the world as figuring out the “why” behind a long-running problem?

But then, just as Icarus became so entranced by the miracle of flight that he lost his common sense, I too forgot I soared on wax-wrought wings, and flew too close to the sun.

LLMs are not the Enterprise-D’s computer

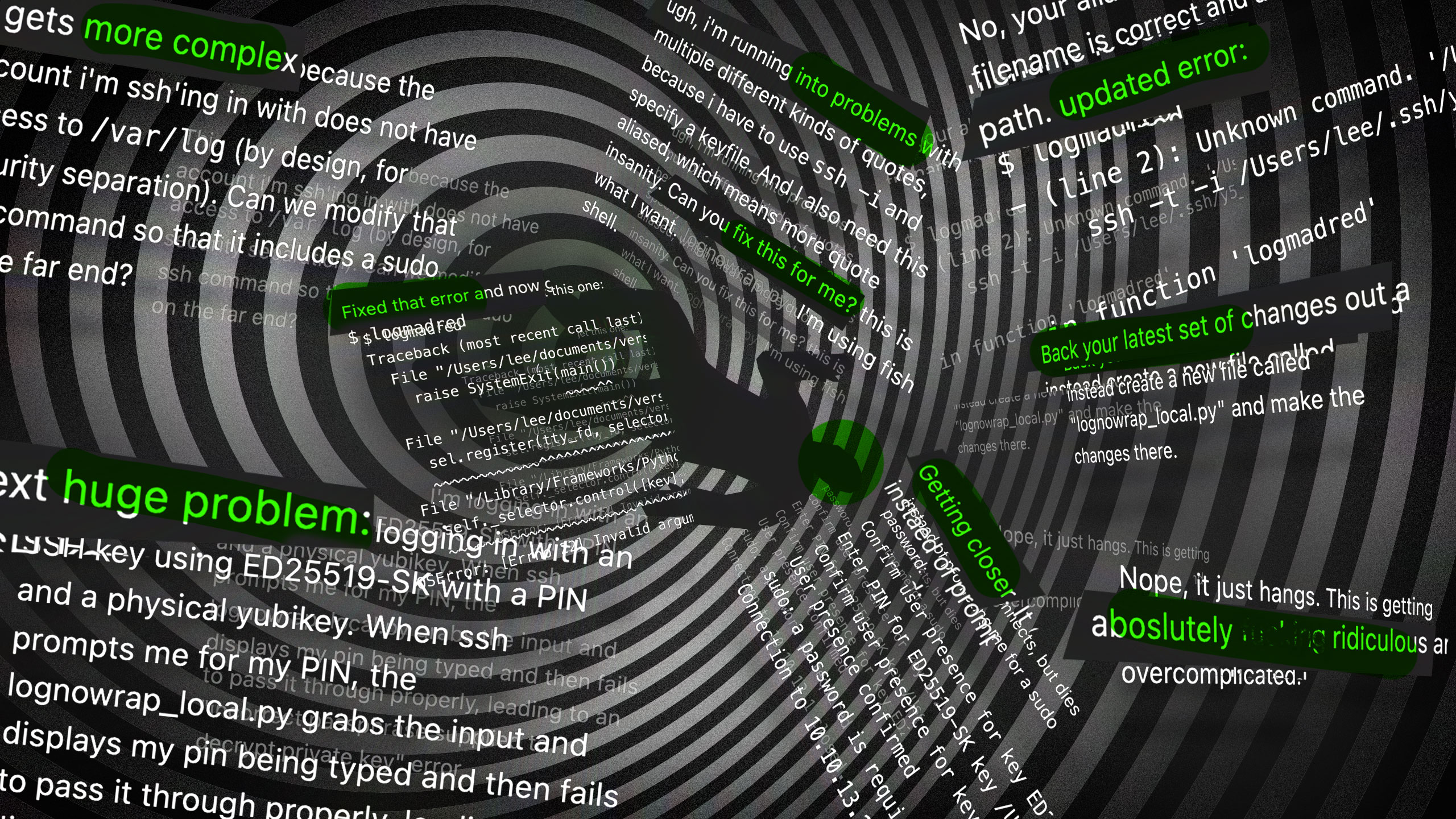

I think we all knew I’d get here eventually—to the inevitable third act turn, where the center cannot hold, and things fall apart. If you read Benj’s latest experience with agentic-based vibe coding—or if you’ve tried it yourself—then what I’m about to say will probably sound painfully obvious, but it is nonetheless time to say it.

Despite their capabilities, LLM coding agents are not smart. They also are not dumb. They are agents without agency—mindless engines whose purpose is to complete the prompt, and that is all.

What this means is that, if you let them, Claude Code (and OpenAI Codex and all the other agentic coding LLMs) will happily spin their wheels for hours hammering on a solution that can’t ever actually work, so long as their efforts match the prompt. It’s on you to accurately scope your problem. You must articulate what you want in plain and specific domain-appropriate language, because the LLM cannot and will not properly intuit anything you leave unsaid. And having done that, you must then spot and redirect the LLM away from traps and dead ends. Otherwise, it will guess at what you want based on the alignment of a bunch of n-dimensional curves and vectors in high-order phase space, and it might guess right—but it also very much might not.

Lee loses the plot

So I had my log colorizer, and I’d found my problem. I’d also found, after leaving the colorizer up in a window tailing the web server logs in real time, all kinds of things that my previous behavior of occasionally glancing at the logs wasn’t revealing. Ooh, look, there’s a rest route that should probably be blocked from the outside world! Ooh, look, there’s a web crawler I need to feed into Cloudflare’s WAF wood-chipper because it’s ignoring robots.txt! Ooh, look, here’s an area where I can tweak my fastcgi cache settings and eke out a slightly better hit rate!

But here’s the thing with the joy of problem-solving: Like all joy, its source is finite. The joy comes from the solving itself, and even when all my problems are solved and the systems are all working great, I still crave more joy. It is in my nature to therefore invent new problems to solve.

I decided that the problem I wanted to solve next was figuring out a way for my log colorizer to display its output without wrapping long lines—because wrapped lines throw off the neatly delimited columns of log data. I would instead prefer that my terminal window sprout a horizontal scroll bar when needed, and if I wanted to see the full extent of a long line, I could grab the scroll bar and investigate.

Astute readers will at this point notice two things: first, that now I really was reinventing lnav, except way worse and way dumber. Second, and more importantly, line-wrapping behavior is properly a function of the terminal application, not the data being displayed within it, and my approach was misguided from first principles. (This is in fact exactly the kind of request that can and should be slapped down on StackOverflow—and, indeed, searching there shows many examples of this exact thing happening.)

But the lure of telling the machine what to do and then watching the machine weave my words into functional magic was too strong—surely we could code our way out of this problem! With LLMs, we can code our way out of any problem! Right?

Eventually, after much refining of requirements, Claude produced what I asked it to produce: a separate Python script, which accepted piped input and created, like, a viewport or something—I don’t know, I can’t code, remember?—and within that viewport, I could scroll around. It seemed to work great!

Problems became apparent when I actually tried scrolling around for more than a short distance—and by “problems,” I mean “my web server’s CPU lit up like a Christmas tree on fire.”

“Issue,” I told the LLM. “When horizontal scrolling happens, the log wrapper takes up almost 100 percent of a host CPU core. Can we assess how to make this a zero-CPU-impact tool?”

“This tool has to parse ANSI, slice lines, and repaint when you scroll,” it replied in what I imagined was an arch, droll tone. “The bottleneck is screen redraw + full-width scan of all lines on every new line or key repeat. Each new line triggers a full screen redraw of term_height lines, plus visible_width() over the entire buffer. Holding the arrow key generates rapid repeats, each doing a full redraw and slice of every line.”

I was crestfallen.

“Zero-CPU isn’t achievable,” continued the LLM, “but there are low-impact approaches.”

My crest lifted a bit, and we dug in—but the LLM was perhaps a bit optimistic about those “low-impact approaches.” We burned several more days’ worth of tokens on performance improvements—none of which I had any realistic input on because at this point we were way, way past my ability to flail through the Python code and understand what the LLM was doing. Eventually, we hit a wall.

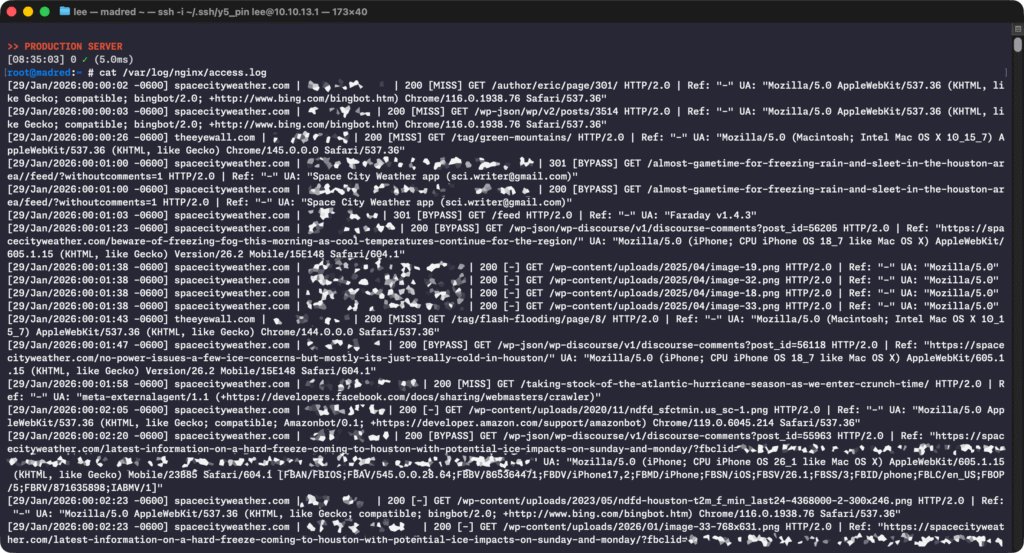

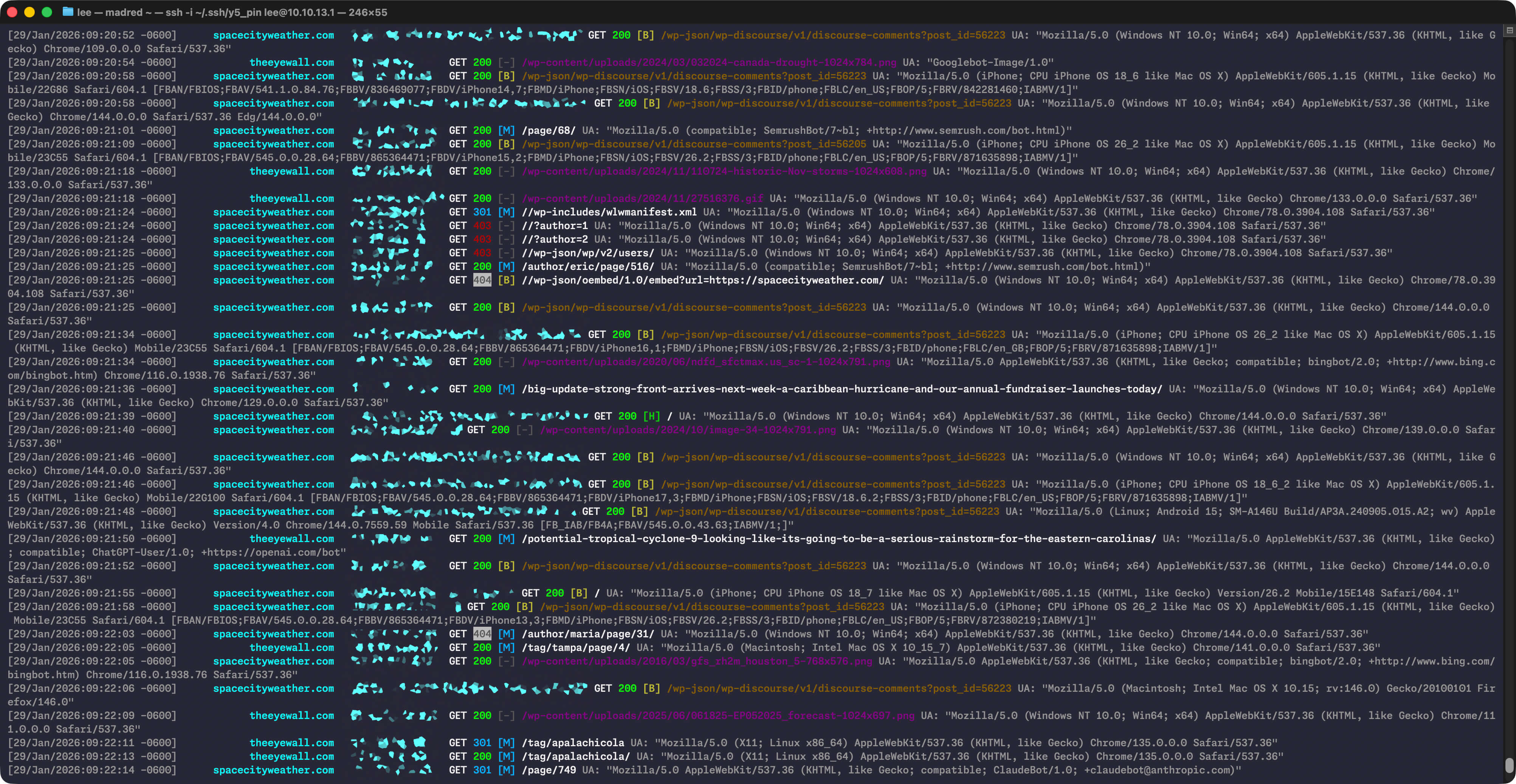

Instead of throwing in the towel, I vibed on, because the sunk cost fallacy is for other people. I instructed the LLM to shift directions and help me run the log display script locally, so my desktop machine with all its many cores and CPU cycles to spare would be the one shouldering the reflow/redraw burden and not the web server.

Rather than drag this tale on for any longer, I’ll simply enlist Ars Creative Director Aurich Lawson’s skills to present the story of how this worked out in the form of a fun collage, showing my increasingly unhinged prompting of the LLM to solve the new problems that appeared when trying to get a script to run on ssh output when key auth and sudo are in play:

The bitter end

So, thwarted in my attempts to do exactly what I wanted in exactly the way I wanted, I took my log colorizer and went home. (The failed log display script is also up on GitHub with the colorizer if anyone wants to point and laugh at my efforts. Is the code good? Who knows?! Not me!) I’d scored my big win and found my problem root cause, and that would have to be enough for me—for now, at least.

As to that “big win"—finally managing a root-cause analysis of my WordPress-Discourse-Cloudflare caching issue—I also recognize that I probably didn’t need a vibe-coded log colorizer to get there. The evidence was already waiting to be discovered in the Nginx logs, whether or not it was presented to me wrapped in fancy colors. Did I, in fact, use the thrill of vibe coding a tool to Tom Sawyer myself into doing the log searches? (“Wow, self, look at this new cool log colorizer! Bet you could use that to solve all kinds of problems! Yeah, self, you’re right! Let’s do it!”) Very probably. I know how to motivate myself, and sometimes starting a task requires some mental trickery.

This round of vibe coding and its muddled finale reinforced my personal assessment of LLMs—an assessment that hasn’t changed much with the addition of agentic abilities to the toolkit.

LLMs can be fantastic if you’re using them to do something that you mostly understand. If you’re familiar enough with a problem space to understand the common approaches used to solve it, and you know the subject area well enough to spot the inevitable LLM hallucinations and confabulations, and you understand the task at hand well enough to steer the LLM away from dead-ends and to stop it from re-inventing the wheel, and you have the means to confirm the LLM’s output, then these tools are, frankly, kind of amazing.

But the moment you step outside of your area of specialization and begin using them for tasks you don’t mostly understand, or if you’re not familiar enough with the problem to spot bad solutions, or if you can’t check its output, then oh, dear reader, may God have mercy on your soul. And on your poor project, because it’s going to be a mess.

These tools as they exist today can help you if you already have competence. They cannot give you that competence. At best, they can give you a dangerous illusion of mastery; at worst, well, who even knows? Lost data, leaked PII, wasted time, possible legal exposure if the project is big enough—the “worst” list goes on and on!

To vibe or not to vibe?

The log colorizer is not the first nor the last bit of vibe coding I’ve indulged in. While I’m not as prolific as Benj, over the past couple of months, I’ve turned LLMs loose on a stack of coding tasks that needed doing but that I couldn’t do myself—often in direct contravention of my own advice above about being careful to use them only in areas where you already have some competence. I’ve had the thing make small WordPress PHP plugins, regexes, bash scripts, and my current crowning achievement: a save editor for an old MS-DOS game (in both Python and Swift, no less!) And I had fun doing these things, even as entire vast swaths of rainforest were lit on fire to power my agentic adventures.

As someone employed in a creative field, I’m appropriately nervous about LLMs, but for me, it’s time to face reality. An overwhelming majority of developers say they’re using AI tools in some capacity. It’s a safer career move at this point, almost regardless of one’s field, to be more familiar with them than unfamiliar with them. The genie is not going back into the lamp—it’s too busy granting wishes.

I don’t want y’all to think I feel doomy-gloomy over the genie, either, because I’m right there with everyone else, shouting my wishes at the damn thing. I am a better sysadmin than I was before agentic coding because now I can solve problems myself that I would have previously needed to hand off to someone else. Despite the problems, there is real value there, both personally and professionally. In fact, using an agentic LLM to solve a tightly constrained programming problem that I couldn’t otherwise solve is genuinely fun.

And when screwing around with computers stops being fun, that’s when I’ll know I’ve truly become old.

Lee Hutchinson

Senior Technology Editor

Lee Hutchinson

Senior Technology Editor

Lee Hutchinson

Senior Technology Editor

Lee Hutchinson

Senior Technology Editor

Netflix says users can cancel service if HBO Max merger makes it too expensive

There is concern that subscribers might be negatively affected if Netflix acquires Warner Bros. Discovery’s (WBD's) streaming and movie studios businesses. One of the biggest fears is that the merger would lead to higher prices due to Netflix having less competition. During a Senate hearing today, Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos suggested that the merger would have an opposite effect.

Sarandos was speaking at a hearing held by the US Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Antitrust, Competition Policy, and Consumer Rights, “Examining the Competitive Impact of the Proposed Netflix-Warner Brothers Transaction.”

Sarandos aimed to convince the subcommittee that Netflix wouldn’t become a monopoly in streaming or in movie and TV production if regulators allowed its acquisition to close. Netflix is the largest subscription video-on-demand (SVOD) provider by subscribers (301.63 million as of January 2025), and WBD is the third (128 million streaming subscribers, including users of HBO Max and, to a smaller degree, Discovery+).

Nvidia's $100 billion OpenAI deal has seemingly vanished

Nvidia’s $100 billion OpenAI deal has seemingly vanished

Two AI giants shake market confidence after investment fails to materialize.

Story text

Size

Small

Standard

Large

Width

*

Standard

Wide

Links

Standard

Orange

* Subscribers only

Story text

Size

Small

Standard

Large

Width

*

Standard

Wide

Links

Standard

Orange

* Subscribers onlyLearn more

In September 2025, Nvidia and OpenAI announced a letter of intent for Nvidia to invest up to $100 billion in OpenAI’s AI infrastructure. At the time, the companies said they expected to finalize details “in the coming weeks.” Five months later, no deal has closed, Nvidia’s CEO now says the $100 billion figure was “never a commitment,” and Reuters reports that OpenAI has been quietly seeking alternatives to Nvidia chips since last year.

Reuters also wrote that OpenAI is unsatisfied with the speed of some Nvidia chips for inference tasks, citing eight sources familiar with the matter. Inference is the process by which a trained AI model generates responses to user queries. According to the report, the issue became apparent in OpenAI’s Codex, an AI code-generation tool. OpenAI staff reportedly attributed some of Codex’s performance limitations to Nvidia’s GPU-based hardware.

After the Reuters story published and Nvidia’s stock price took a dive, Nvidia and OpenAI have tried to smooth things over publicly. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman posted on X: “We love working with NVIDIA and they make the best AI chips in the world. We hope to be a gigantic customer for a very long time. I don’t get where all this insanity is coming from.”

What happened to the $100 billion?

The September announcement described a wildly ambitious plan: 10 gigawatts of Nvidia systems for OpenAI, requiring power output equal to roughly 10 nuclear reactors. Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang told CNBC at the time that the project would match Nvidia’s total GPU shipments for the year. “This is a giant project,” Huang said.

But the deal was always a letter of intent, not a binding contract. And in recent weeks, Huang has been walking back the number. On Saturday, he told reporters in Taiwan that the $100 billion was “never a commitment.” He said OpenAI had invited Nvidia to invest “up to” that amount and that Nvidia would “invest one step at a time.”

“We are going to make a huge investment in OpenAI,” Huang said. “Sam is closing the round, and we will absolutely be involved. We will invest a great deal of money, probably the largest investment we’ve ever made.” But when asked if it would be $100 billion, Huang replied, “No, no, nothing like that.”

A Wall Street Journal report on Friday said Nvidia insiders had expressed doubts about the transaction and that Huang had privately criticized what he described as a lack of discipline in OpenAI’s business approach. The Journal also reported that Huang had expressed concern about the competition OpenAI faces from Google and Anthropic. Huang called those claims “nonsense.”

Nvidia shares fell about 1.1 percent on Monday following the reports. Sarah Kunst, managing director at Cleo Capital, told CNBC that the back-and-forth was unusual. “One of the things I did notice about Jensen Huang is that there wasn’t a strong ‘It will be $100 billion.’ It was, ‘It will be big. It will be our biggest investment ever.’ And so I do think there are some question marks there.”

In September, Bryn Talkington, managing partner at Requisite Capital Management, noted the circular nature of such investments to CNBC. “Nvidia invests $100 billion in OpenAI, which then OpenAI turns back and gives it back to Nvidia,” Talkington said. “I feel like this is going to be very virtuous for Jensen.”

Tech critic Ed Zitron has been critical of Nvidia’s circular investments for some time, which touch dozens of tech companies, including major players and startups. They are also all Nvidia customers.

“NVIDIA seeds companies and gives them the guaranteed contracts necessary to raise debt to buy GPUs from NVIDIA,” Zitron wrote on Bluesky last September, “Even though these companies are horribly unprofitable and will eventually die from a lack of any real demand.”

Chips from other places

Outside of sourcing GPUs from Nvidia, OpenAI has reportedly discussed working with startups Cerebras and Groq, both of which build chips designed to reduce inference latency. But in December, Nvidia struck a $20 billion licensing deal with Groq, which Reuters sources say ended OpenAI’s talks with Groq. Nvidia hired Groq’s founder and CEO Jonathan Ross along with other senior leaders as part of the arrangement.

In January, OpenAI announced a $10 billion deal with Cerebras instead, adding 750 megawatts of computing capacity for faster inference through 2028. Sachin Katti, who joined OpenAI from Intel in November to lead compute infrastructure, said the partnership adds “a dedicated low-latency inference solution” to OpenAI’s platform.

But OpenAI has clearly been hedging its bets. Beyond the Cerebras deal, the company struck an agreement with AMD in October for six gigawatts of GPUs and announced plans with Broadcom to develop a custom AI chip to wean itself off of Nvidia dependence. When those chips will be ready, however, is currently unknown.

Benj Edwards

Senior AI Reporter

Benj Edwards

Senior AI Reporter

Benj Edwards

Senior AI Reporter

Benj Edwards